It’s very clear to all honest observers that the rental market in Ontario is brutal for tenants. And despite what landlords and developers—and their pundits—might say, it’s not actually some deeply complex and unsolvable conundrum. Policy-makers could have a large and immediate impact by fixing the various problems with Ontario’s rent control system.

Rent control will not solve structural inequalities brought about by land speculation, profit-seeking in housing markets, and the financialization of rental housing. But strong rent controls can slow rent increases and improve security of tenure—which would be concrete, if limited, gains for the tenant class. From a technical perspective, fixing rent control is straightforward. From a political perspective, it’s an uphill battle. We’ll look at each in turn.

Policy solutions

The four measures listed below would make Ontario’s rent control regime more effective. The first two have been done before; the other two would be new to Ontario but exist elsewhere. Each of these measures could be implemented independently, but a government truly concerned with skyrocketing rents and tenant rights would implement all four measures.

1. End the 2018 exemption

In 1976, the PC government included a date-based exemption in the new rent control regulation. In 1985, the new Liberal government ended the exemption. In 1998, the PC government brought it back. Between 2003 and 2016, Liberal governments chose not to touch the exemption, finally ending it in 2017. The PC government of Doug Ford brought it back in 2018, within only six months of being in power. This is clearly a political choice.

2. Re-enact vacancy control

Ontario had vacancy control from 1985 to 1998. Two CMHC studies covering this period didn’t find negative effects associated with this policy. However, Toronto City Council did see the negative effect of decontrol on affordability. In 2008, council urged the provincial government to re-enact vacancy control to slow down the pace of rent increases. The motion quoted Liberal Leader Dalton McGuinty promising to “get rid of vacancy decontrol.”1 That never happened. Another clear political choice.

3. Replace above-guideline rent increases (AGIs) with conditional government support

Poorly managed buildings fall into disrepair; it is in the public interest to repair these buildings and prevent acquisitions from financialized landlords. But tenants should not pay the price. The burden should be on landlords to apply for conditional subsidized loans from the federal and provincial governments.

First, landlords would have to provide proof that rent income is not sufficient to cover the cost of renovations. Then, conditions for loans might include strictly following rent increase guidelines (including in vacant units), disclosing financial statements, involving tenant unions in management decisions, and giving the right of first refusal to municipal governments and non-market housing providers in case of bankruptcy.

Governments already provide subsidized loans and costly tax breaks to the real estate industry, with few conditions attached. Renovation loans would likely have a more direct impact on rent levels, keeping buildings in good repair and increasing accountability.

4. Extend collective bargaining rights to organized tenants

Rent regulation sets the minimum protections that apply to all tenants, just as the minimum wage and health and safety laws set standards that apply to all workers. However, minimum standards only create a floor, not optimal outcomes. Organized tenants ought to be able to collectively bargain for better rents and living conditions, just as labour unions bargain for better wages and working conditions.

Tenancy regulation should recognize tenant unions as legal representatives of tenants and require landlords to engage in good-faith negotiations with them, subject to arbitration and legal recourse. In Sweden, most of the rental stock is part of a collective bargaining system.2

Political responses

Studies and ideas will not change minds when so much wealth is at stake. It takes a political fight. It always has. Across the country, for more than a century, tenants have organized to push back against exploitation. When governments approved laws that benefited tenants, it was in response to political pressure, not brilliant ideas.

Researchers should continue to compile data on real-world rent control scenarios. Today, the claim that minimum wage increases kill jobs is hardly taken seriously because of the piles of empirical evidence showing they don’t. We’re not there yet with rent control.

Housing policy analysts should stand up to bullies who try to shut down rent regulation debates. This hardly happens in professional public policy spaces, where self-preservation comes first. But for folks willing to give it a try, the evidence presented here should be helpful.

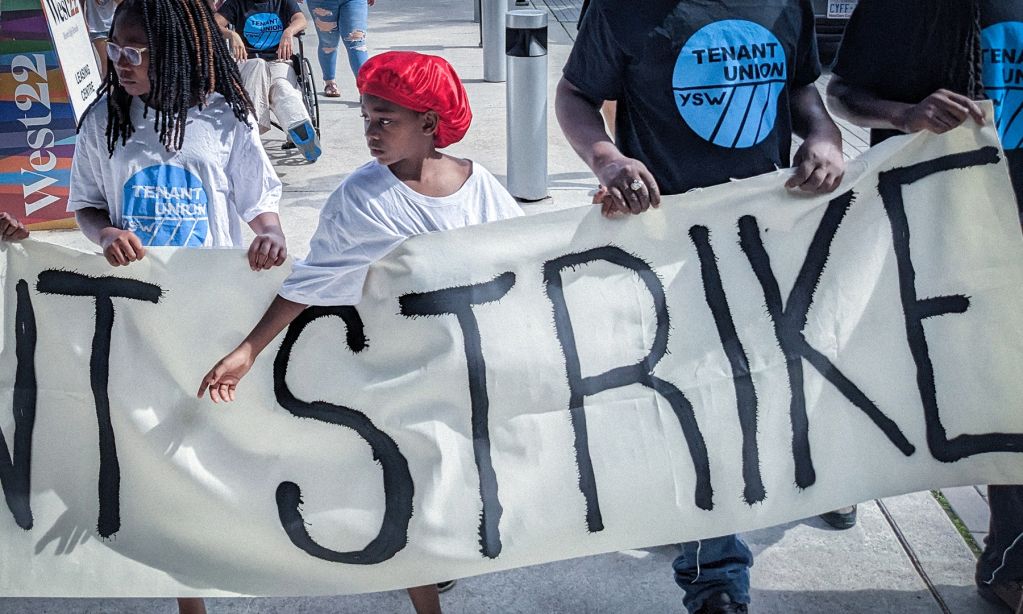

But the most important work is building political power. Organized tenants are the ones doing this work, creating the political conditions for change at the local and other levels.

As of March 2024, more than 600 tenants were on rent strike in Toronto. The strike on Thorncliffe Park Drive started in May 2023. The strike in York South-Weston started a month later, with more buildings joining over the following months. In most of the buildings on strike, the issue at stake is AGIs.3

There are other documented examples of tenants successfully fighting AGIs by filing official challenges through the LTB but also focusing their efforts on organizing outside of the LTB process and directly pressuring landlords.4

Evictions don’t go unchallenged, either. “Through self-organization, non-reliance on legal strategy, and directly confronting their landlords, tenants have successfully pressured their landlords to withdraw evictions before they ended up at hearings in front of the LTB.”5

Numerous other examples exist of tenants fighting landlords and the political establishment that supports them. Housing advocates, researchers, and public policy specialists spend an immense amount of resources, energy, and time on policy debates and official consultations. We should invest more of those resources and energy into work that directly supports tenant organizing.