Executive summary

This study examines the gap between the minimum wage and what it costs to rent an apartment in Canada. The rental wage measure provides a clear picture of the relationship between wages and rents because it calculates the hourly wage required to afford rent while working a standard 40-hour week and spending no more than 30 per cent of one’s income on housing. In other words, the rental wage is how much people need to earn to pay rent without spending too much of their income on it.

The rental wage is considerably higher than minimum wage in every single province. Even in the three provinces with the highest minimum wage in Canada—B.C., Ontario, and Alberta—there’s a shortfall in what minimum-wage workers earn and the rent they have to pay, on average. Interactive rental wage details are available by province, city and neighbourhood.

In practice, this means that the higher minimum wages in these provinces don’t directly translate into better living conditions because landlords capture a larger share of those wages through high rents. The wage increases that people fought so hard for should improve the material conditions of working families, not go back into the pockets of the property-owning class.

When we look at Canadian cities (CMAs), the story is equally stark: the one-bedroom rental wage is lower than the minimum wage in only three CMAs. All are in Québec: Sherbrooke, Trois-Rivières, and Saguenay. Even there, rental affordability is on the decline. Every other CMA in Canada has average rents that far exceed what workers earn on the minimum wage.

Vancouver and Toronto are the worst culprits: even two full-time minimum wage workers cannot afford a one-bedroom unit without spending more than 30 per cent of their combined income on housing.

The discrepancy between the rental wage and the minimum wage is such that, in most Canadian cities, minimum-wage earners are extremely unlikely to escape core housing need. They are likely spending too much on rent, living in units that are too small, or, in many cases, both.

The findings presented in this report should not be interpreted simply as a supply and demand problem. At least three sets of factors make rent too high for low-wage earners: wage suppression policies; low supply of rental housing, especially purpose-built, rent-controlled, and non-market units; and poorly regulated rental markets that privilege profit-making over housing security and allow the use of rental accommodation as an asset class. In other words, the mess in which we find ourselves is due to bosses keeping wages down with help from provincial governments that set the minimum wage and federal governments that control monetary policy.

It’s also due to governments’ collective failure to build, finance, and acquire the right kinds of rental housing, which is compounded by landlords who use their political influence to weaken rental market regulations, allowing them to increase rents and profit margins. Markets do not solve the problems they create. When the desired outcome is housing security rather than profit, governments must regulate markets and support non-market housing.

1. Introduction

Housing affordability debates often focus exclusively on rent levels or consider income indirectly through rent-to-income ratios. In contrast, the rental wage measure provides a clear picture of the relationship between wages and rents because it calculates the hourly wage required to afford rent while working a standard 40-hour week and spending no more than 30 per cent of one’s income on housing. In other words, the rental wage is how much people need to earn to pay rent without spending too much of their income on it.

The rental wage for any area can be compared with different income measures (e.g., the minimum wage, the living wage, social assistance rates, and wage deciles), depending on the focus of the analysis. This report presents the rental wage for all provinces and census metropolitan areas (CMAs) and compares them with the local minimum wage. It also looks into 776 neighbourhoods in Canada within those CMAs, providing a detailed picture of affordability across the country.

With a few exceptions, the minimum wage falls well below the rental wage. In every province, the rental wage for one- and two-bedroom units is higher than the minimum wage. In 34 out of 37 CMAs, the minimum wage is lower than the one-bedroom rental wage. In 35 of 37 CMAs, a minimum-wage worker cannot afford a two-bedroom unit without spending more than 30 per cent of their income on rent. In 93 per cent of all neighbourhoods (for which data is available), the one-bedroom rental wage is higher than the minimum wage.

This report also includes comparisons with the findings in our 2018 rental wage report.1 Between 2018 and 2022, rents have become even less affordable to minimum-wage workers, with average rents now consuming a larger number of working hours in most CMAs. Even in Québec, where rents are comparatively more affordable, the trend is worrisome.

Our findings should not be interpreted simply as a supply and demand problem. While evidence shows the supply of rental housing is lagging demand, additional supply alone will not address affordability issues, especially for low- and moderate-income families. To put it simply: additional supply is necessary but not sufficient.

What is built, where it is built, and under what regulatory framework is equally important. Canada needs more purpose-built rental units. Canada needs a larger share of rental housing outside of the private, for-profit rental market. Canada needs regulation that prevents profiteering in the private rental market. More housing anywhere at any cost will simply enrich developers and allow landlords to continue to extract ever higher rents from the tenant class.2

2. Methodology

The rental wage calculation is inspired by the National Low Income Housing Coalition’s annual Out of Reach study of affordable housing in the United States.4 The estimated amount would allow tenants to spend no more than 30 per cent of their pre-tax earnings on rent and it assumes tenants work a standard 40-hour week for all 52 weeks of the year. The 30 per cent rent-to-income threshold is one of three criteria (alongside adequacy/state of repair and suitability/correct number of rooms) used by the CMHC to determine core housing need. If a tenant household spends more than 30 per cent of its income on housing, that household is considered to be living in unaffordable housing.

Two-bedroom apartments are the most common rental type in Canada (50 per cent of all purpose-built units),5 and data for them is less likely to be suppressed in CMHC data, especially at the neighbourhood level outside of central-city areas. A two-bedroom unit also acts as a proxy for various family types in Canada, since it provides a modest amount of room for multiple people to live in. Many households rely on only one income but contain more than one person: a single parent, a single-income family or an adult caring for a senior, to list a few examples. In a country as rich as Canada, a sole-income earner working full time should be able to afford a modest two-bedroom apartment for their family. In most cities, this is just not the case.

One-bedroom units make up 33 per cent of the rental stock; less data is available for them. Since the number of persons living alone in Canada more than doubled in the past 35 years,6 and singles living in poverty are not receiving enough attention in policy debates,7 we calculated the rental wages for one-bedroom units, where possible, in this 2023 version of the report.

Bachelor (six per cent) and three-bedroom or more (11 per cent) apartments make up the remainder of the rental stock. We did not calculate the rental wages for these unit sizes. Townhomes, which are less common and generally more expensive to rent, are excluded from this study.

Rent data were obtained from CMHC’s Housing Market Information Portal, which displays data from CMHC’s Rental Market Survey (RMS).8 Only cities with a population of 10,000+ and buildings with three or more rental units are included in the RMS and, therefore, in this analysis.9 CMHC also conducts a secondary rental market survey to determine average rents for condominiums.10 The condominium and apartment datasets are rarely combined to create an average rent across both, but that has been done in all figures in this report unless otherwise noted. The average rent for other types of secondary market housing (e.g., entire houses and second units within a house) are excluded due to lack of data. Average rents are for both occupied and vacant units. Since rent for unoccupied units is higher, averages underestimate rental costs for units that are actually available on the market.11

We have used provincial minimum wages at their October 2022 level to match the time frame of the rental data survey. Some provincial minimum wages have gone up since then, but as we will see below, these increases do not affect rental affordability.

Table 5 in the Appendix presents the share of one-person households with total income at or below the equivalent of a full-year, full-time minimum-wage job in 2021. (We used 2021 wages to match the year of the Canada Housing Survey). The share varies from 21 per cent to 42 per cent, depending on the province. An estimated 828,000 people were in that situation, nationally. The same table presents the share of households of two or more people with household income at or below the equivalent of two full-year, full-time minimum-wage jobs in that province in 2021. The share varies from eight per cent to 31 per cent, depending on the province. Across the country, an estimated 459,000 households, or 1.1 million people, were in this situation. As presented below, the combined income of two people earning the minimum wage is not sufficient to afford one- or two-bedroom units in some cities. Other research has detailed the housing needs of different low-income groups.12

Generally, median and average rental costs are quite similar in most of the neighbourhoods studied here, with the notable exception of Vancouver and Toronto, where the average rent is significantly higher than the median.13 We have attempted to overcome any shortcomings of using the average rent as the measure of central tendency by examining trends at the neighbourhood level. Readers can check the rental wage in their neighbourhood by consulting the interactive rental wage map on the CCPA website.

Census metropolitan areas combine large cities and densely populated areas surrounding them. For example, Toronto’s CMA covers most the GTA (Greater Toronto Area), Montreal’s CMA includes Laval and the South Shore, Vancouver’s CMA includes most of the Lower Mainland. CMAs are often considered the local level for housing and labour markets since people consider housing and job opportunities within their broader region and don’t limit their choices to city limits. The Ottawa-Gatineau CMA has a somewhat integrated housing market but different minimum wages; we opted to use the separated data—Ottawa (Ontario side) and Gatineau (Québec side). Charlottetown, while not a CMA, is still included as it is the provincial capital.

3. Rental wages across Canada in 2022

Province by province

The rental wage is considerably higher than the minimum wage in every province, as seen in Table 1. The gap between the minimum wage and one-bedroom rental wages varies from $2.24 (16 per cent) in Newfoundland and Labrador to $11.89 (76 per cent) in B.C. Québec has the smallest proportional gap between the minimum wage and the two-bedroom rental wage, but even there, workers need to earn $4.46 (31 per cent) more per hour to afford a unit without spending too much of their income. In B.C. the two-bedroom rental wage is over twice as much as the minimum wage. Ontario and Nova Scotia have two-bedroom rental wages just under twice the minimum wage.

In the province that had the highest minimum wage in the country as of October 2022, British Columbia ($15.65), minimum-wage workers cannot afford an apartment without spending more than 30 per cent of their income, on average. In fact, British Columbia and Ontario had the two highest minimum wages but also the two highest rental wages in the country. Alberta’s minimum wage was the third highest and it was still 43 per cent below the one-bedroom rental wage.

In practice, this means that the higher minimum wages in these provinces don’t directly translate into better living conditions because landlords capture a larger share of those wages through high rents. Hard fought for wage increases should improve the material conditions of working families, not go back into the pockets of the property-owning class.

City by city

Gone are the days when exorbitant rents were a peculiarity of Toronto and Vancouver. Table 2 shows that the one-bedroom rental wage is lower than the minimum wage in only three CMAs. All are in Québec: Sherbrooke, Trois-Rivières, and Saguenay.

But affordability is diminishing in some of these CMAs. In Sherbrooke, the 2018 minimum wage exceeded the one-bedroom rental wage by 18 per cent; in 2022, it did so by only nine per cent. If this trend continues, one-bedroom units in that city may soon become out of reach to minimum-wage earners. (More on Québec trends below).

In Vancouver and Toronto, even two full-time minimum-wage workers cannot afford a one-bedroom unit without spending more than 30 per cent of their combined income on housing.

Single-earner families earning the minimum wage that require a two-bedroom apartment can only find an affordable apartment in two CMAs: Trois-Rivières and Saguenay. In the six cities with the highest two-bedroom rental wage—Vancouver, Toronto, Kelowna, Victoria, Ottawa, and Halifax—the rental wage is more than twice the minimum wage (see Table 2). In these six worst rental-wage cities, two full-time minimum wage workers cannot rent a two-bedroom without spending more than 30 per cent of their combined income on housing.

The discrepancy between the rental and minimum wage is such that, in most Canadian cities, minimum-wage earners are extremely unlikely to escape core housing need. They are likely spending too much on rent, living in units that are too small, or, in many cases, both.

Neighborhood by neighborhood

The one-bedroom rental wage is lower than the minimum wage in seven per cent of neighbourhoods across Canada (for which data is available). In only three per cent of neighbourhoods, the two-bedroom rental wage is lower than the minimum wage. Table 3 shows that 27 out of 37 CMAs have no neighborhoods where one-bedroom units are, on average, affordable and 32 CMAs have no neighborhoods where two-bedroom units are, on average, affordable.

Forty-seven out of the fifty-four neighbourhoods with affordable one-bedroom units and all 21 with affordable two-bedroom units are in Québec.14 Elsewhere in the country, finding a neighborhood with affordable units is like finding a needle in a haystack. In Ontario, only three out of 287 neighborhoods have one-bedroom units that would be affordable for a minimum-wage worker, and they are spread across two cities.

An interactive map contains most of the data in this report. It provides users with a bird’s-eye view of provinces, a city-by-city comparison, and the ability to select a city and view neighbourhood-level data. Table 3 provides a summary of neighbourhood findings, which can assist in the use of the interactive map.

4. Rental wage comparisons, 2018 versus 2022

Between 2018 and 2022, the percentage of neighbourhoods with one-bedroom units that are affordable to minimum-wage workers worsened in nine out of 36 CMAs for which data are available. In the other 28 CMAs, there was either no change or a change smaller than 1.5 percentage point. (The complete list of changes is included in the appendix).

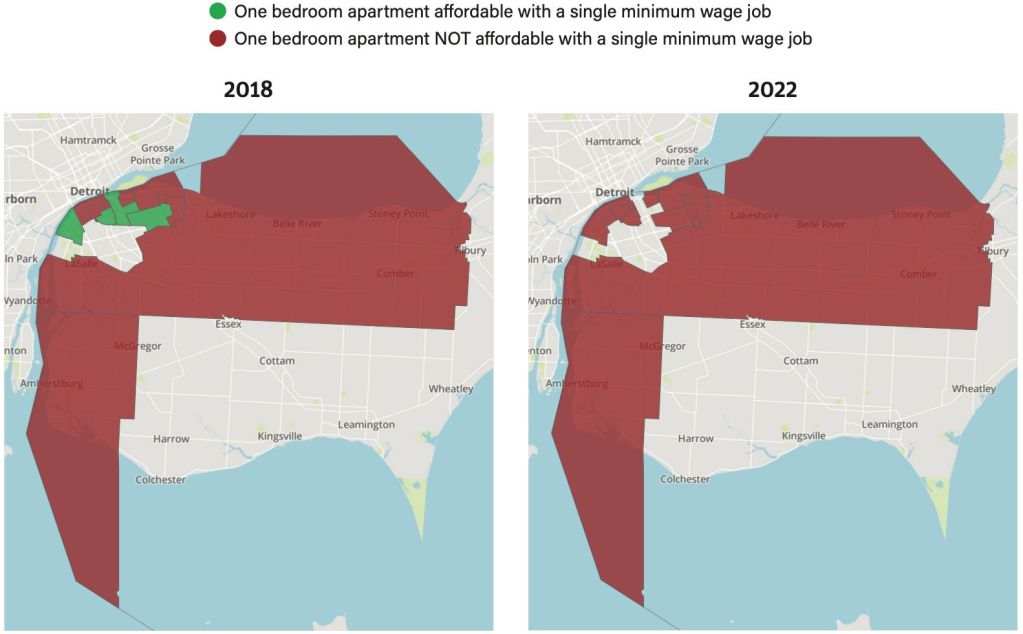

The number of affordable neighborhoods decreased in seven out of nine of the CMAs with visible changes. At the top of that list is Windsor. In 2018, one third, or four out of 12 neighborhoods for which data are available, had affordable one-bedroom units. By 2022, there were none left.

Sherbrooke and Gatineau are also in the list of cities that experienced a decrease in the share of affordable neighbourhoods, reinforcing the concern about low-wage workers being priced out of major centres in that province. Two CMAs saw an increase in the percentage of neighbourhoods with one-bedroom units at a price that minimum-wage workers can afford: Winnipeg (three per cent) and Saint John (10 per cent). In both cases, the increase was due to one neighborhood moving above the threshold, mostly due to an increase in the minimum wage.

The number of minimum wage hours required to pay rents also increased in most cities since 2018. In 2022, rent consumed more hourly wages than it did before in 27 of the 37 CMAs, it remained the same in one CMA, it decreased in the remaining nine CMAs.

While Québec contains most of the more affordable neighborhoods in Canada, Table 4 shows a worrying trend. Three of its largest cities—Montréal, Gatineau, Sherbrooke—saw increases in the number of minimum wage hours required to pay rent. Gatineau had the second largest increase in the country, behind Kelowna. In Gatineau, rent now eats half a week more of work (twenty hours) every month. In the other three Québec CMAs—Québec, Trois-Rivières, and Saguenay—the number of hours remained steady over the four-year period, with no change or a small drop. There is no sign that affordability is improving in Québec and it is visibly worsening in some of its most populated regions.

In sum, a larger share of the hard-worked-for earnings of working-class families is now flowing from bosses to landlords, making the wealthy wealthier and leaving tenants poorer. The so-called housing crisis is often presented as a mismatch between supply and demand, while the obvious transfer of income and wealth from low- to high-income earners is repeatedly overlooked.

5. Supply: Necessary but not sufficient

The findings presented in this report should not be interpreted simply as a supply and demand problem. At least three sets of factors make rent too high for low-wage earners: wage suppression policies; low supply of rental housing, especially purpose-built, rent-controlled, and non-market units; and poorly regulated rental markets that privilege profit-making over housing security and allow the use of rental accommodation as an asset class. In other words, the mess in which we find ourselves is due to bosses keeping wages down, with help from provincial governments that set the minimum wage and federal governments that control monetary policy.15 It’s also due to governments’ collective failure to build, finance, and acquire the right kinds of rental housing,16 which is compounded by landlords who use their political influence to weaken rental market regulations, allowing them to increase rents and profit margins.17

The explanation we often hear is much simpler. The CMHC Rental Market report (2023 edition), an authoritative source in the field, states that, “Growth in demand outpaced strong growth in supply, pushing the vacancy rate for purpose-built rental apartments down from 3.1% to 1.9%... Rent growth, for its part, reached a new high.”18 In other passages of the report, the suggested casual relationship is stated even more clearly, “Strong demand for limited rental units means low vacancy rates, rising rents.”19 Media commentary echoes this simplified explanation: “Rental housing vacancy rates in Canada were 1.9 per cent compared to 3.1 per cent a year ago, leading to a 5.4 per cent increase in rent inflation.”20 Examples abound.

This common overemphasis on supply-side arguments is not accidental: it’s a political choice. If we believe lack of supply is the sole cause of skyrocketing rents, the solution is building more. If we build more but rents continue to go up, we must not be building enough. Build more! How? Governments must provide financial and regulatory incentives to developers, the argument goes, and weaken rent controls, like the Ontario government is doing, so that landlords find the business more attractive. This narrow supply-side argument serves a clear purpose: to sweeten the deal for developers and landlords. The argument has been made for decades; it has justified countless subsidies for the real estate industry; it has not lowered rents.21

Supply is necessary but not sufficient to address affordability concerns. Even a careful literature review in defence of supply-side arguments has concluded so.22 It matters what gets built, where, and under which regulatory framework. To directly improve affordability for low- and moderate-income families, governments must focus their dollars on financing, building, and acquiring purpose-built, rent-controlled, and non-market housing that provide fairly priced rents—now and in the long term.23 They must also properly regulate the rental market by fully implementing rent controls on occupied and vacant units and abolishing above-guideline rent increase loopholes.

Markets do not solve the problems they create. When the desired outcome is housing security rather than profit, governments must regulate markets and support non-market housing.