[CW: Anti-Asian racism]

One hundred and fifteen years ago this September, downtown Vancouver was beset by thousands of protesters rallying against Asian immigration to Canada. Over the course of the event, moods shifted and the crowd turned violent. While the reasons for the gathering in Vancouver then and the ongoing “Freedom Convoy” today differ, there are similarities and lessons to be learned. It may seem an odd choice to study a painful chapter of Canada’s history in an already-too painful moment. However, historian Barrington Walker offers insight into its importance. “It’s not about just digging up unpleasant stories about Canada; it’s about challenging a certain notion of our historical innocence.”1

The riots

The 1907 riots did not occur in a vacuum. They were the result of years of building tension exacerbated by an economic downturn in 1907. After years of financial boom, the global demand for British Columbia’s resources slowed and unemployment reached record high levels.2 “Workers and politicians were looking for someone to blame,” explains historian Julie Gilmour, “and ‘cheap [Asian] labour’ had become a regular target.”3

The popular consensus was that Vancouver was being overrun by Asian immigrants. This fear was largely unfounded–in 1903, Prime Minister Laurier had radically increased the head tax on Chinese immigrants from $100 to $500 per person, essentially stymying Chinese immigration to the country.4 Much of the panic about a growing Japanese population was based on misinformation and bad statistics that counted Japanese people travelling through Canada with their final destination being elsewhere and counting previously immigrated Japanese residents returning from abroad.5

The fears over Asian immigration reached a fever pitch when a series of ships carrying Japanese migrants from Hawaii arrived in the Vancouver harbours between April and September of 1907. While the majority of the ships carried fewer than 300 passengers, one ship, the Kumeric, arrived in July with a reported 1,177 Japanese migrants onboard.6 Again, not all of these passengers would remain in Vancouver or even Canada, but that did not matter. The Vancouver Daily Province reported the ship’s arrival, suggesting that it was the start of a large-scale inundation of Canada by Japanese migrants. The article was accompanied by a photograph of passengers on the ship’s deck, referring to them as a “swarm of ants.”7

In response to the arrivals, on August 12, 1907, the Vancouver Trades and Labour Council founded the Vancouver Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL), with the city’s mayor, Alexander Bethune and several city councillors as founding members. The Vancouver AEL would join a patchwork of Asian Exclusion Leagues along the West coast, working closely with the Seattle AEL.8

The Vancouver riots began on the evening of September 7 outside of a special City Hall meeting that Alderman Stewart had requested to deal “with reclusion of [Asians].”9 Ahead of the meeting, the Vancouver AEL organized a parade to march to the meeting and rally outside. Thousands of people turned out, of which only a portion could fit in the standing-room-only audience in chambers. Outside, the overflow supporters lit bonfires, held their signs calling for “a White Canada for us” and burned an effigy of B.C. lieutenant-governor James Dunsmuir.10

During the official meeting, the rally had a “carnival-like atmosphere.”11 Accounts of what happened next are murky. Official records point to American A.E. Fowler, the secretary of the Anti-Japanese and Korean League of Seattle, inciting violence. After finishing his official remarks inside, Fowler addressed the rally. Following this, the crowd began to march into Chinatown, where the violence and destruction began.12

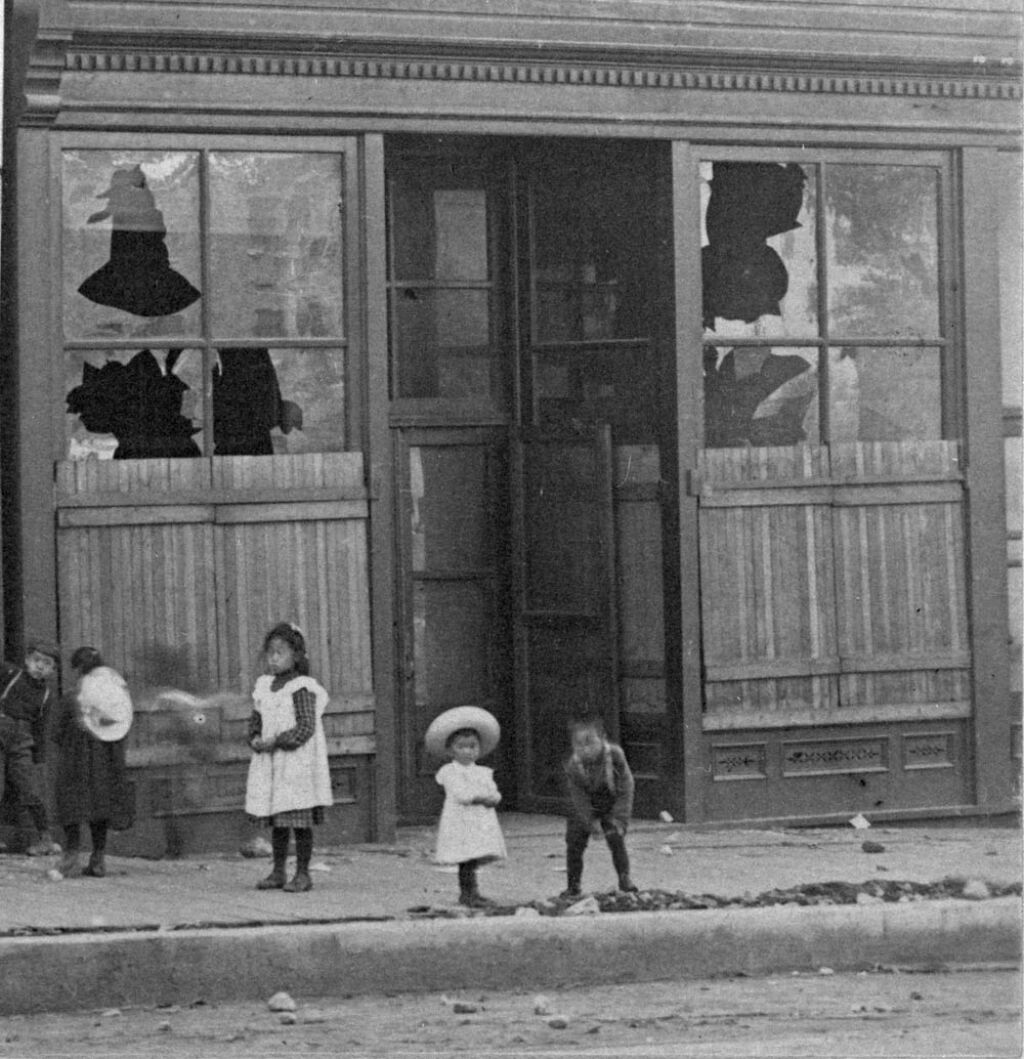

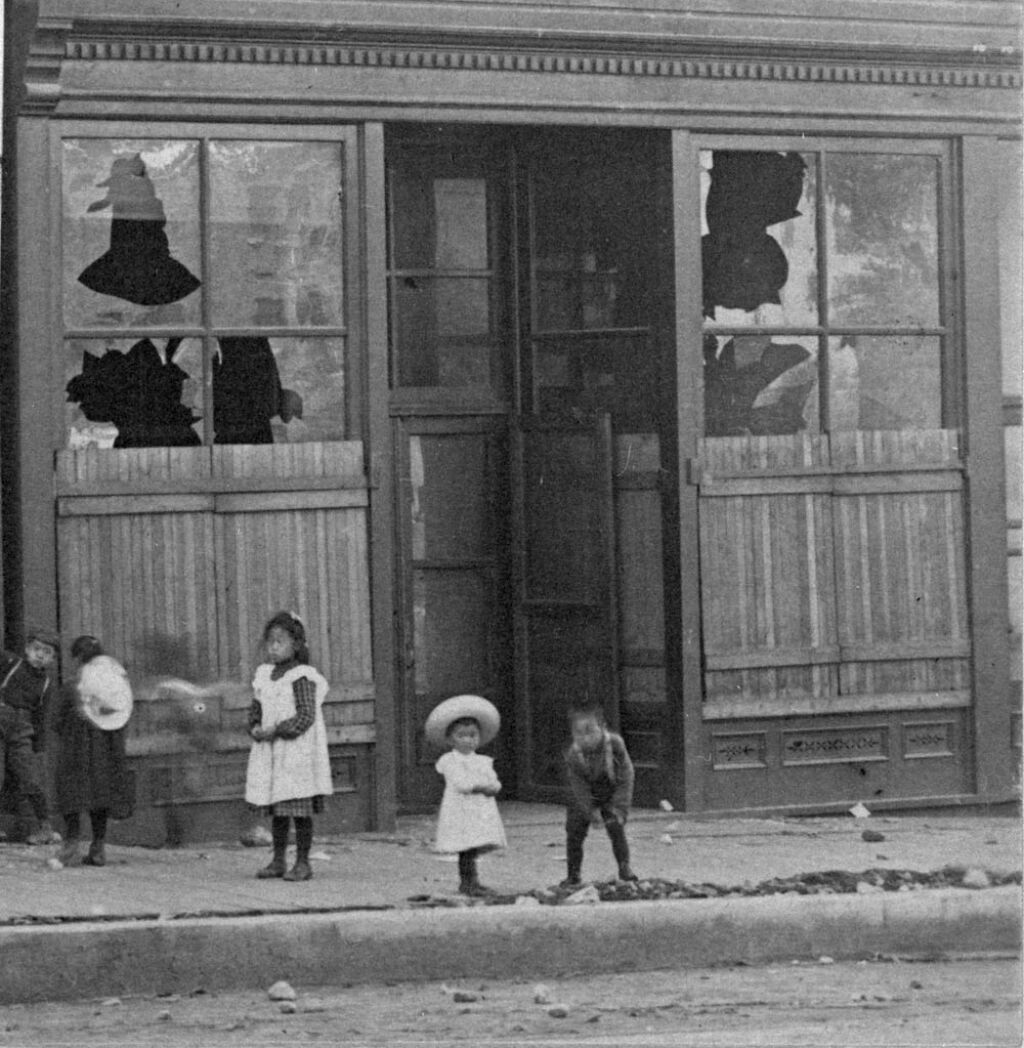

The rioters threw rocks and bricks through the windows of Chinese businesses. However, when they arrived on Powell Street, where the Japanese businesses were located, they encountered an organized and armed group of Japanese men ready to defend their community who chased off the rioters.13

On Monday, Chinese workers coordinated a general strike to protest the violence inflicted on their community. White rioters returned, setting fire to the Japanese Language School, the Japanese Methodist Church and the Hastings Sawmill, which employed many Japanese workers. All three fires were extinguished before they could spread.14

While official history remembers the riots as being a series of violent acts that occurred between September 7 and 9, William Lyon Mackenzie King would report that Japanese residents felt under threat for a period of two weeks following the initial attacks.15

The Reaction

British and Canadian leaders were upset by the Vancouver riots, not for the overt racism on display but because they demonstrated “an embarrassing breakdown in civility,” an embarrassment for Canadians made “all the keener due to the fact that these events had an international audience and might have serious [international] consequences.”16 The violence threatened important agreements between Canada, Britain and Japan, including the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902.

Gilmour notes that by 1907, Britain had placed their relationship with Japan at the centre of their strategy to contain both Russia and Germany. “Naturally Laurier was incensed by the lawlessness in Vancouver. He was… concerned about the implications for Canada’s foreign relations with Britain and Japan.”17 The fact that the official response was focused on restoring official reputation and maintaining lucrative agreements is made most obvious by the discrepancy in care afforded to the two communities impacted by the riot. While Japan was a top priority, Canada’s relationship with China was considered far less valuable. As a result, when Prime Minister Laurier called the governor general on September 9 to discuss how to respond to the violence, “neither [Laurier] nor the governor general mentioned at all the approximately 3,500 Chinese residents of Vancouver who had been victims of the riots.”18

By December, the commission to assess damages to the Japanese community began. The Chinese commission would not begin until the following May. William Lyon Mackenzie King was assigned to lead the commissions.

King wanted to understand what factors had led to the violence. In his July 1908 report, he concluded, “uncontrolled immigration from Japan to B.C. was the cause of the rioting,” noting, “the residents of Vancouver should have experienced some concern” about increased immigration from Japan, China and India.19

An additional official cause was identified as leading to the violence. Canadian and British officials named American instigators as playing a pivotal role in inciting violence.20 The British paper, The Times reiterated this blame:

The leaders of the demonstration were not Canadians, but citizens of the United States. They were Frank Cotterill, president of the Federation of Labour of the State of Washington, A.E. Fowler, secretary of the Anti-Japanese and Korean League of the same State, and George P. Listman, a prominent Labour leader of Seattle...The actual acts of violence seem to have been committed for the most part by Canadians, but that the violence was due to the agitation of the Americans there appears to be not a shadow of doubt.21

Woan-Jen Wang’s comparative study of Asian language newspapers with English newspapers found that the riots were covered very differently in Chinese- and Japanese-language newspapers. “Chinese newspapers, unlike local English newspapers, reported the long history of local anti-Asian organizing, refusing to assign [cause solely] to the agitation of Americans and the Asiatic Exclusion League.”22 Wang notes that the hostility that led up to the 1907 riots did not dissipate with them but led to another small anti-Japanese riot in January 1908. More troublingly, it fuelled a series of anti-Asian legislation.23

Following King’s report, Prime Minister Laurier sent Minister of Labour Rodolphe Lemieux to Tokyo to discuss immigration. During his visit, Lemieux cautioned his host that reducing the number of immigrating labourers was necessary to maintaining the “happy relations” between the two countries and preventing further anti-Japanese hostilities in British Columbia.24 This “Gentlemen’s Agreement” between Lemieux and Count Hayashi significantly limited Japanese immigration to Canada.25

The Hayashi-Lemieux Agreement was just the first piece of legislation to come out of the riot’s aftermath. Soon after came the 1908 Continuous Journey Act, essentially ending immigration from India as continuous travel from India to Canada was not yet possible. In 1923, Canada passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned most forms of immigration from China to Canada. The “Gentlemen’s Agreement” was amended in both 1924 and 1928, eventually capping the annual number of Japanese immigrants at 150.26 Then, in 1941, Japanese Canadians were required to register with both the RCMP and the Registrar of Enemy Aliens, and Japanese fishing boats began to be impounded. Soon after, the government declared the area within 100 miles of the west coast a “protected area” and on February 7, 1942, ordered all male “enemy aliens” between ages 18-45 to leave the protected area by April 1, leaving their families behind. On February 26, a dusk-to-dawn curfew was imposed for all remaining Japanese Canadians in the area, and they were ordered to prepare to leave the protected area.27

A similar message rippled through Ottawa during the occupation: that (white, settler) residents needed to Take Back Ottawa. The underlying assumption being, of course, that it is ours to take.

Lessons for today

While the inciting incidents that led to the protests in 1907 and 2022 were different, the two events share key characteristics.

The role of the media

In 1907, the media played two critical roles: stoking anger and fear about immigrants while admonishing the mob violence for the political embarrassment it caused. Roy notes that the day prior to the violence, the Vancouver Daily Province ran a story about more Japanese immigrants arriving. On the first day of the riot, the paper ran a story with the attention grabbing (and emotion stirring) lede “[Asian] Hordes on MONTEAGLE… over 2,000 [Chinese] had left Yokohama on that Canadian Pacific Steamship.”28

In the aftermath of the riot, the focus of English newspapers was on the potential for international embarrassment, not the impact on local residents. Wang notes that English newspapers focused their sympathy on federal British officials who had to deal with this incident.29 While leaders including Laurier and Roosevelt shared the belief that North America needed to be preserved as a white homeland, media stories were quick to point out that breaking windows was not the method by which to safeguard this future.

A similar pattern has played out in present day mainstream media. The continued downplaying of the risks of COVID-19 infections by mainstream reporting continually casts doubt on the need for public health measures and contributes to growing frustration.

The early coverage of the Freedom Convoy was most concerned about disrespect of the National War Memorial and Terry Fox statue, but not the impact it had on the residents stuck in the red zone. Further, there was an unwillingness among journalists covering the occupation to label the behaviour of the participants as violent. The lack of a nuanced definition of violence prevented reporters from accurately capturing the depth of harm caused by a 26 day occupation that included physical attacks on community members, a bomb threat called in to a local hospital, 24/7 noise pollution that frequently reached 110 decibels, intentionally flooding 911 with calls so that residents could not reach emergency services, the flying of hateful imagery including the Nazi and Gadsden flags and more. If our media will only recognize violence at its most extreme, journalists are failing to document the ways that extremist movements have damaged our communities.

In 1907 the riots received political attention because of the strategic importance of Japan to Britain at the time, and because Canadian and British officials were embarrassed by the overt lawlessness of the events. Similarly, the Freedom Convoy garnered attention after bridges between the U.S. and Canada were occupied. When Canadian officials moved to end the blockades American media outlets took notice of the ongoing protests.

Underlying assumptions allow for dangerous outcomes

In 1907, everyone in a position of leadership agreed that the “[Asian] problem” was serious and in need of attention. As King wrote after one meeting, “that Canada should remain a white man’s country is to be not only desirable for economic and social reasons …[it] is necessary on political and national grounds.”30 It’s worth noting that Europeans were, themselves, colonizers in this place and the idea that they would then get to deem Canada as a country for white people is in and of itself problematic as it remained home to many Indigenous nations.

Still, because the underlying assumptions were the need to prevent further embarrassment and restore stability, the real threats to Asian Canadian communities remained. In fact, because King identified Asian immigration as a cause for the riot, the violence became an excuse for future xenophobic legislation.

A similar message rippled through Ottawa during the occupation: that (white, settler) residents needed to Take Back Ottawa. The underlying assumption being, of course, that it is ours to take. The views represented on the Hill during the occupation were an extension, albeit an extreme on, of the unaddressed white supremacy upon which Canada is founded.

We must also resist the urge to see this movement as one that was simply about public health mandates. The recent arrival of the Rolling Thunder convoy in Ottawa, over a month after the removal of mask mandates, should be evidence enough that this movement never was about public health measures. If Canada today does not consider how ongoing radicalization is intertwined with anti-lockdown messaging, the racism, trans and homophobia that were present in Ottawa this winter will continue to spread.

Toxic populism and nationalism

Both Patricia Roy and Walker revealed in their research the centrality of nationalistic imagery to the protest movements of 1907. o Walker, a “toxic populism” was critical to mobilizing supporters in Vancouver, a trend that he now sees re-emerging. The marchers in 1907 carried banners and signs that would not have been out of place at the Freedom Convoy protests this year. Many were strongly identified with the maple leaf and symbols of patriotism. Nationalism, it seems, offers easily repurposed, high-value signifiers like the Canadian flag that have warped and continue to warp into powerful signifiers for white nationalism.31

In both 1907 and 2022, economic insecurity has been weaponized to garner support for violent forms of populism. While the 2022 protests did direct anger at elected officials, calls did not aim to increase supports for affected workers and close widening inequality gaps.

An unwillingness to confront white supremacy

This final takeaway is a recognition that 115 years have passed since the Vancouver race riots. We have learned and grown as a nation in that time. While it would have been a tall order to suggest that King and his contemporaries confront white supremacy, that’s less the case today. In fact, now it is imperative. That includes acknowledging that, while the Freedom Convoy protests may have included international actors, it was a homegrown movement. We gain nothing from comforting ourselves with tales of foreign influence.

The longer we give space to white supremacy and oxygen to ideas rooted in hatred and fear of others, the longer we permit violence and create unsafe situations for historically marginalized communities. The Occupation of Ottawa shouldn’t make us angry because people laughed at Canada. It should make us angry that racialized, queer and disabled people weren’t safe to leave their homes for a month. It should make us angry that when a certain class of white people get upset in this country, they can lash out without consequence. We had an established white supremacy problem before the first brick went through a window in 1907, and we have one now. Changing immigration policy then didn’t solve it, and eliminating mask mandates now won’t end it. Until we actually confront the root and dismantle systems that enable white supremacy, we are ensuring future violence against the most marginalized members of our communities.

Resources

The following resources can be helpful guides for learning more about the 1907 riots and their role within Canada's history.

360 Riot Walk: This interactive walking tour of the 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver. It utilizes 360 video technology to trace the history and route of the mob that attacked the Chinese Canadian and Japanese Canadian communities following the demonstration and parade organized by the Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver.

White Supremacy, Political Violence, and Community: The Questions We Ask, from 1907 to 2017: Written in 2017, article looks back at 1907 through the lens of recent protests, connecting the recent history with the not-too-distant past.

The History of Canada Series: Trouble on Main Street: This book documents William Lyon Mackenzie King's journey as the head of the commissions and statesman sent to maintain relations with American counterparts in the aftermath of the riots. It is a solid account of the bureaucratic side of the crisis.

Patricia Roy's Trilogy: Possibly some of the most thorough research on Canada's racist policies of this era are documented by Patricia Roy. Her book series, A White Man's Province, The Oriental Question, and The Triumph of Citizenship are available through the publisher.

Acknowledgements

Thank you to Jenny at the University of British Columbia Initiative for Student Teaching and Research in Chinese Canadian Studies and Patricia Roy for their help with this piece.