When the first trucks rolled in on January 28, I knew something bad was coming our way. What I didn’t realize at the time was that nobody had a plan to stop them.

Many participants have described the first weekend of the occupation as a joyous, celebratory event—a gathering of like-minded individuals—akin to Canada Day. It didn’t take much sleuthing for me to discover the true intentions of those who had descended on our city.

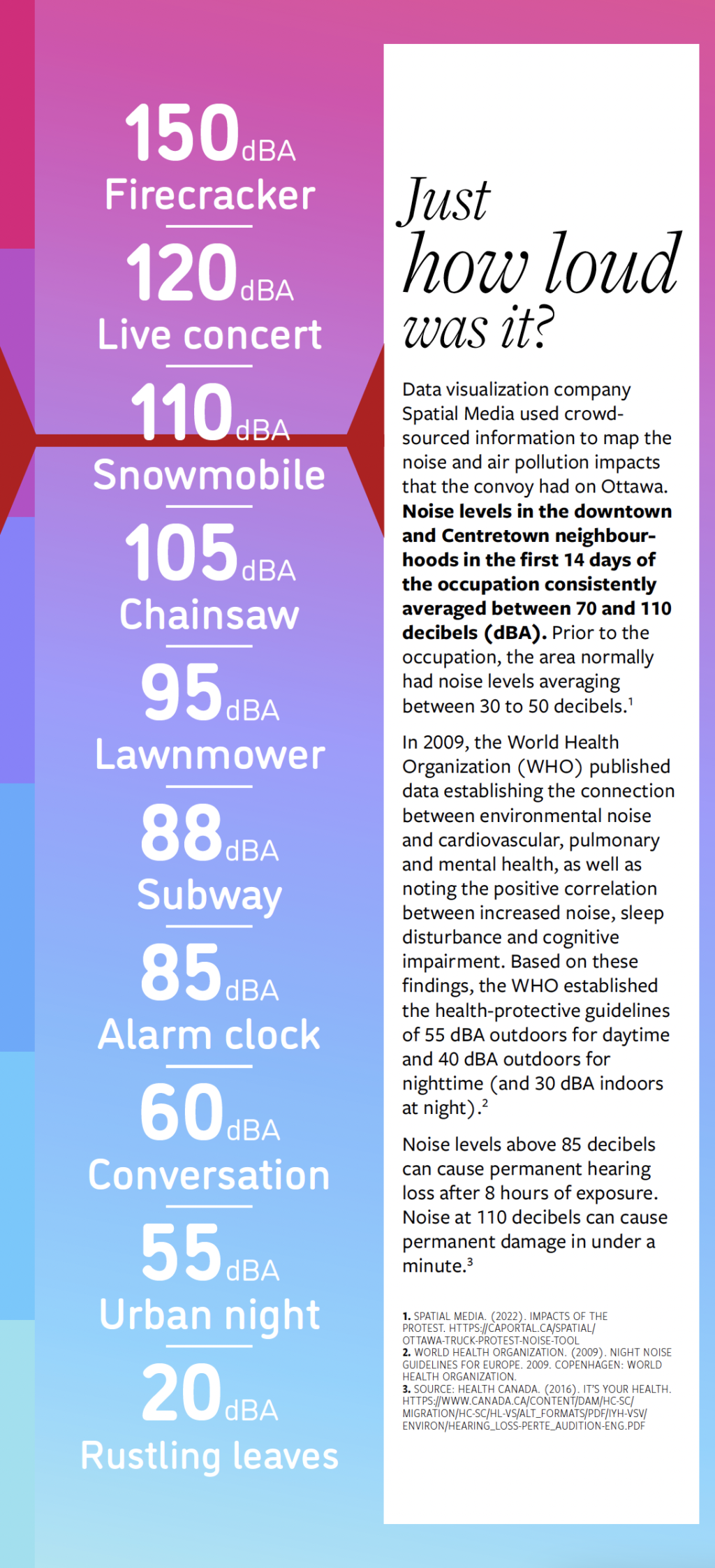

What first stood out to me was their use of noise. Often downplayed as “just some honking,” the noise produced by transport trucks carrying aftermarket horns—which one occupier described to me as “no louder than 140 decibels”—produced noise at an ear-splitting volume that was constant and unbearable. Given the roving pickup truck carrying a literal train horn in its bed, an air raid siren across from my home and the miscellaneous honks that accompanied every sound, it’s no wonder that so many who lived down-town needed to escape their homes for a modicum of rest. This so-called protest had taken up residence in our streets, but it had also invaded our homes and disrupted our lives for that same reason.

Let’s be clear: this was not a protest. The intention from the very start was to hold the residents of Ottawa hostage and to make our lives so unbearable that we had no choice but to heed their demands—which were garbled at best. These rambling demands covered everything from the anti-mandate demands that they were supposedly here for, to calls for Justin Trudeau to be removed from office and tried for crimes against the Canadian population, as well as conspiracies about the government working with the World Trade Organization to track and control vaccinated individuals. Combined with their use of a constant barrage

of noise and their imposition of sleep deprivation—an internationally recognized method of torture—it was clearly demonstrated that these individuals could not be reasoned with, negotiated with, or allowed to stay.

Demonstrating disregard and apathy for residents’ suffering, the Ottawa Police Service (OPS) continuously described the occupation as a peaceful, successful protest while Ottawa’s leadership expressed their appreciation in blissful—and perhaps willful—ignorance. It was exceedingly difficult to watch this narrative repeated, and each time it was, a little bit of my hope was chipped away.

By February 3, I decided that I had had enough. For over a week, I had observed the occupation firsthand: watching and listening in awe of the absurd reality we were living in. I made an effort to speak to many of the police officers I encountered, mostly to find out why they were allowing this to happen. Some responded dispassionately, while others suggested they were sympathetic but unable to act.

Regardless of their reasons, the OPS observing from a distance while the law was being broken in every direction only fanned the flames of resident frustrations and emboldened the occupiers to continue their siege. The tensions in downtown Ottawa were rising, and many of us felt that a response would soon be seen, not from the OPS, but from the residents—particularly when the OPS made statements suggesting that nobody was calling them or reporting any issues, which was unequivocally untrue. I found myself organizing a meeting with OPS community liaison officers and residents of my building for us to air our grievances, demand help and establish accountability—nobody would be able to say that the Ottawa Police Service was unaware of our issues. My secret intention for the meeting was to diffuse some of the anger many of my neighbours were feeling, as I worried immensely about any kind of resident-occupier confrontation. I’d like to think it helped.

By this point, it was quite clear that our city would not be leading a solution so time was of the essence.

From this community meeting I was identified as a candidate for the lead plaintiff of the class-action lawsuit. Paul Champ and his team had been working on the case but they were having difficulty getting an individual to put their name on it, largely due to valid concerns over safety. After the meeting, Paul Champ called to inform me of the work they were trying to accomplish. In particular, the potential for the injunction against noise resonated deeply with me. I agreed to be the lead plaintiff almost immediately. This wasn’t a frivolous decision by any means, but we were desperate for any kind of action. By this point, it was quite clear that our city would not be leading a solution so time was of the essence. I knew that members of my community were suffering—both those that I knew personally and those that I didn’t, but all of whom I cared about.

Personally, I felt some hesitation and doubt, primarily because I knew that I wasn’t the worst off. There were countless young children, elderly residents, those living with physical and mental illnesses and so many others that were more gravely affected than me, and I feared that my own experience was not enough to emphasize the real harm that was being dealt to these particularly vulnerable communities. However, I did come to the eventual realization that I had to stand up and offer a voice for the people impacted. I knew I had the strength and resilience to weather the guaranteed slew of hate and vitriol that would, and did, come because of the injunction.

The legal team had told me that putting my name on the case was more than enough to help the community, but as I watched the inaccurate depiction of what was happening in my city, it was important that I offered another perspective, as the lead plaintiff and as a resident of the community living through what I often described as a hellscape.

Speaking out painted an especially large target on my back, resulting in everything from generalized hate messages, to having my address and number leaked, and, of course, the extreme conspiracies dreamed up by creative occupiers (and occupier sympathizers). All these responses were expected, and really, they didn’t mean much to me. What was unexpected, however, was the positive response to my actions and appearances on the news.

One of the rays of hope throughout this experience has been how the community was able to unite in the face of such extreme hardship. Neighbours from down the hall and those from across the country alike came together to offer support, kindness and encouragement, while recognizing and condemning what was happening in Ottawa. We had finally been heard, and while it took far longer than it should have, we took back our city. The damage from the occupation lingers in our streets, homes and minds, but at the very least, we can

start our recovery in peace.

On February 4, 2022, a class-action lawsuit was filed against the Freedom Convoy protestors with Zexi Li as the lead plaintiff. On February 7, an Ontario Superior Court justice granted a 10-day injunction against horn honking. The injunction was later expanded to include discharging fireworks, idling vehicles and setting fires.

On March 23, Mayor Jim Watson and Councillor Catherine McKenney presented Li with the Mayor’s City Builder Award for her leadership and inspiring contributions during the occupation.

Header image photo credit: lezumbalaberenjena