One hundred years ago—July 1, 1923—the Canadian government passed “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration.” Known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was an overtly racist law prohibiting the arrival of newcomers from China. It also required all people of Chinese heritage, including the Canadian-born, to register with the federal government in order to stay in the country. Chinese Canadian communities across the country mobilized to lobby against the act but in the end their efforts failed to stop its passage. Thus, July 1 came to be known as “Humiliation Day” for many Chinese Canadians.

On the 100-year anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Monitor is releasing a series analysing the context in which the Act passed, resistance to the law, and its historical legacy. These articles are a serialization of the booklet 1923: Challenging Racism Past & Present, which you can read in full at https://challengingracism.ca/

The tumultuous years of the war and its aftermath saw a growing assertiveness on the part of Indigenous, Black, and Asian Canadian communities as well as radical labour. White elites, however, responded aggressively—at Winnipeg and in Versailles. Measures imposed by the Borden government in 1918-1919 impelled the state toward repressive actions. The forces of white supremacy realigned as they attempted to renew and reinforce control over racialized communities and Indigenous land.

In British Columbia, economic and social elites came together, renewing alliances and fomenting a backlash in BC’s fertile racist terrain. This coincided with the federal government’s attempt to gain greater control over Indigenous peoples. Confrontations ensued as racialized peoples fought to defend their ground while coping with divisions within their respective communities.

Riots in Toronto, Wales, and Halifax were initial signals of troubles to come.

Anti-Greek Riot (Toronto)

In the summer of 1918, a drunk veteran had abused a waiter and been ejected from the Greek-owned White City Café in Toronto. The next day, thousands of veterans gathered to loot and attack every Greek-owned shop in downtown Toronto. The riot reflected continuing prejudice against eastern and southern Europeans by dominant Anglo groups, who spread rumours that Greeks did not fight in the war and were “pro-German.”

Anti-Black Riot (Wales, UK)

In early 1919, white Canadian troops rioted in the Kinmel Park barracks in North Wales while awaiting transportation home. When sergeant major Edward Sealy, on duty as military police and member of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, attempted to arrest an unruly white soldier, the reaction was swift. White soldiers attacked hundreds of members of the Black unit as they went for baths.

A biased military report encouraged readers to conclude, according to historian Melissa Shaw, that Black troops had “audaciously transgressed ‘proper’ racial boundaries.” Further riots by white Canadian soldiers were interpreted by the Canadian media as a response to Black American troops returning home before them.

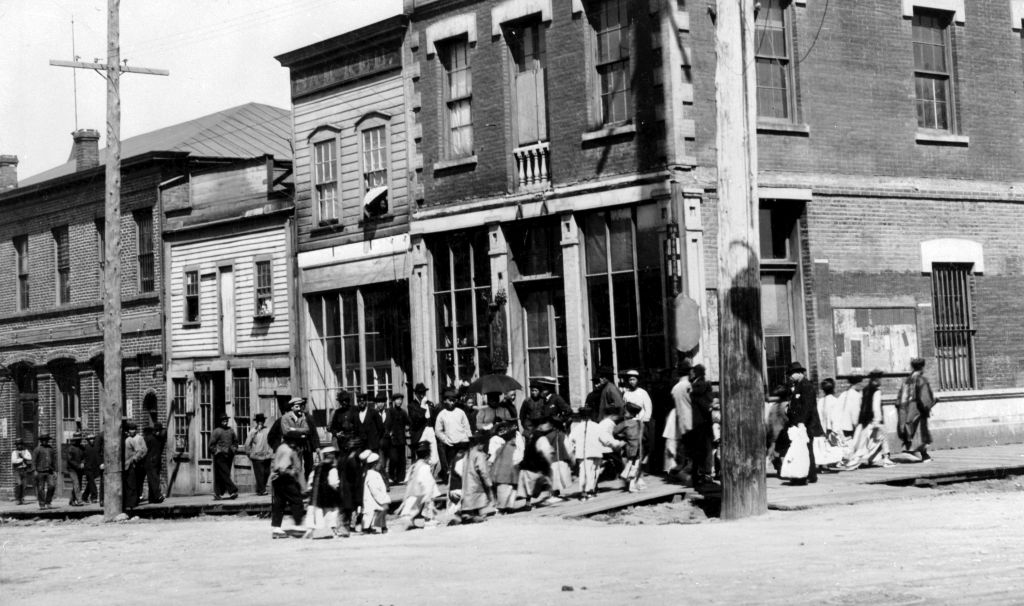

Anti-Chinese Riot (Halifax)

Returned white soldiers rioted and mobbed Chinese stores in February 1919 after a veteran refused to pay his bill and “abused the Chinese proprietor.” When asked to leave he tried to steal cigarettes and cash. After being ejected, he later returned with others and began a two-night rampage, destroying mainly Chinese restaurants and injuring several Chinese residents.

These riots illustrate how some white veterans vented their frustrations against racialized groups who increasingly stood their ground, refused to be intimidated, and defended their comrades, businesses, and communities. The riots, however, were only the beginning.

Fomenting a Backlash

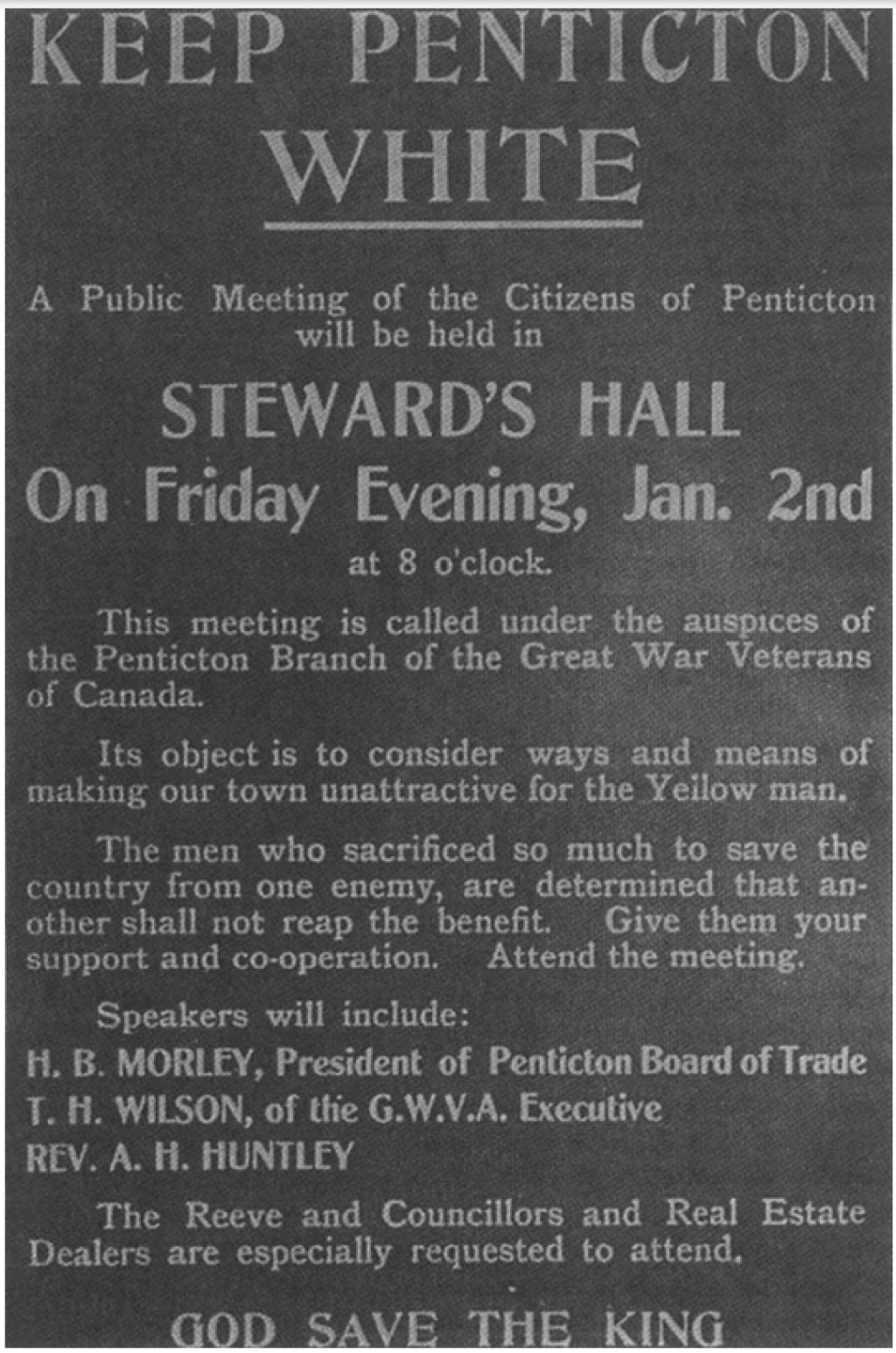

In British Columbia the signs of backlash came fast and furious after the war ended. New Westminster city council passed a motion in February 1919 resolving that “all Asiatic immigration be stopped” and that “all enemy Aliens, as well as Aliens who rendered service to the State during wartime be deported.” The neighbouring municipality of Burnaby opposed “Orientals acquiring land,” and lobbied to restrict Chinese Canadian green grocers and “Oriental retail or wholesale traders.”

Farmers’ organizations lobbied against Asian Canadians acquiring agricultural land. They were joined by the United Farmers of British Columbia and the BC Fruit Growers’ Association, as well as white veterans’ associations, boards of trade, and municipal councils, particularly in the Okanagan. At a Kelowna meeting, these forces declared “the ownership of land in BC by Japanese and Chinese is continually increasing, and constitutes a peril to our ideal of a white British Columbia, as it is impossible for Japanese and Chinese to become assimilated as Canadian citizens.”

Japanese Canadian fishers came under attack as well, having become an important force in the west coast herring, salmon, and cod fisheries. In December 1919, the federal Department of Fisheries issued instructions to reduce the number of gillnet licenses issued to Japanese Canadian fishers every year.

Signs of cross-racial solidarity that had surfaced with the rise of social unionism in 1914-1919 faced major obstacles as craft unions reasserted control over the Vancouver and Victoria Trades and Labour Congress. These organizations actively re-engaged in smearing Asian workers as unfair competitors and inassimilable.

In 1920, white backlash overwhelmed attempts by Japanese Canadians to win a limited right to vote for veterans.

Japanese Canadian Veterans demand the Vote

The Japanese Canadian Association, on behalf of Japanese Canadian veterans who had survived the war, approached the provincial government to revise the voting act to give the 196 veterans the right to vote. Believing they had the support of the Vancouver chapter of the Great War Veterans Association, the government initially accepted the proposal, including an amendment giving them the right to vote in a revised voting act submitted to the legislature in early 1920. The reaction was swift.

White politicians, veterans, unions, farmers, and women’s groups raised furious objections to stop this extremely limited right to vote for 196 Japanese Canadian veterans. In the legislature, MLAs such as W. R. Ross took advantage of the narrow scope of the proposed bill to underscore how it would not give the vote to “Hindus and other East Indians, British subjects, who served the Empire in the war, nor to those Indians of the Province, many of whom enlisted and served overseas.”

The Women’s Canadian Club spoke out formally, stating the issue was one that concerned “the very woof and fabric of the Anglo-Saxon civilization.” They strongly disapproved of any measure granting the vote to the “Japanese or Chinese on any grounds whatsoever,” because to do so fundamentally means the “jeopardizing of our racial traditions and the undermining of Christianity.”

Great War Veterans Associations mobilized widely against the legislation, sending a delegation to Victoria to lobby the cabinet. Labour MLA J. H. Hawthornthwaite stated that he “disliked to draw the colour line,” but from the “standpoint of labour there were objections…the fact that in the past the Japanese had worked for less wages and under conditions under which the whites could not labour had created antagonism between white labour and the Orientals.”

On April 20, the premier formally announced the withdrawal of the proposed legislation enfranchising the veterans. Japanese Canadian veterans, while continuing to lobby for the vote, also persisted by other means, financing a memorial in Stanley Park to their fallen comrades days after the legislation was defeated.

The 1920 campaign against Japanese Canadian veterans’ right to vote heralded the renewed racist ties binding white elites and sectors of civil society, who would go on to propel a white backlash over the next two years. At every turn they would take advantage of divisions between and within communities to advance a racist agenda that would have grave implications across the country.

The Racist Wave Takes Shape

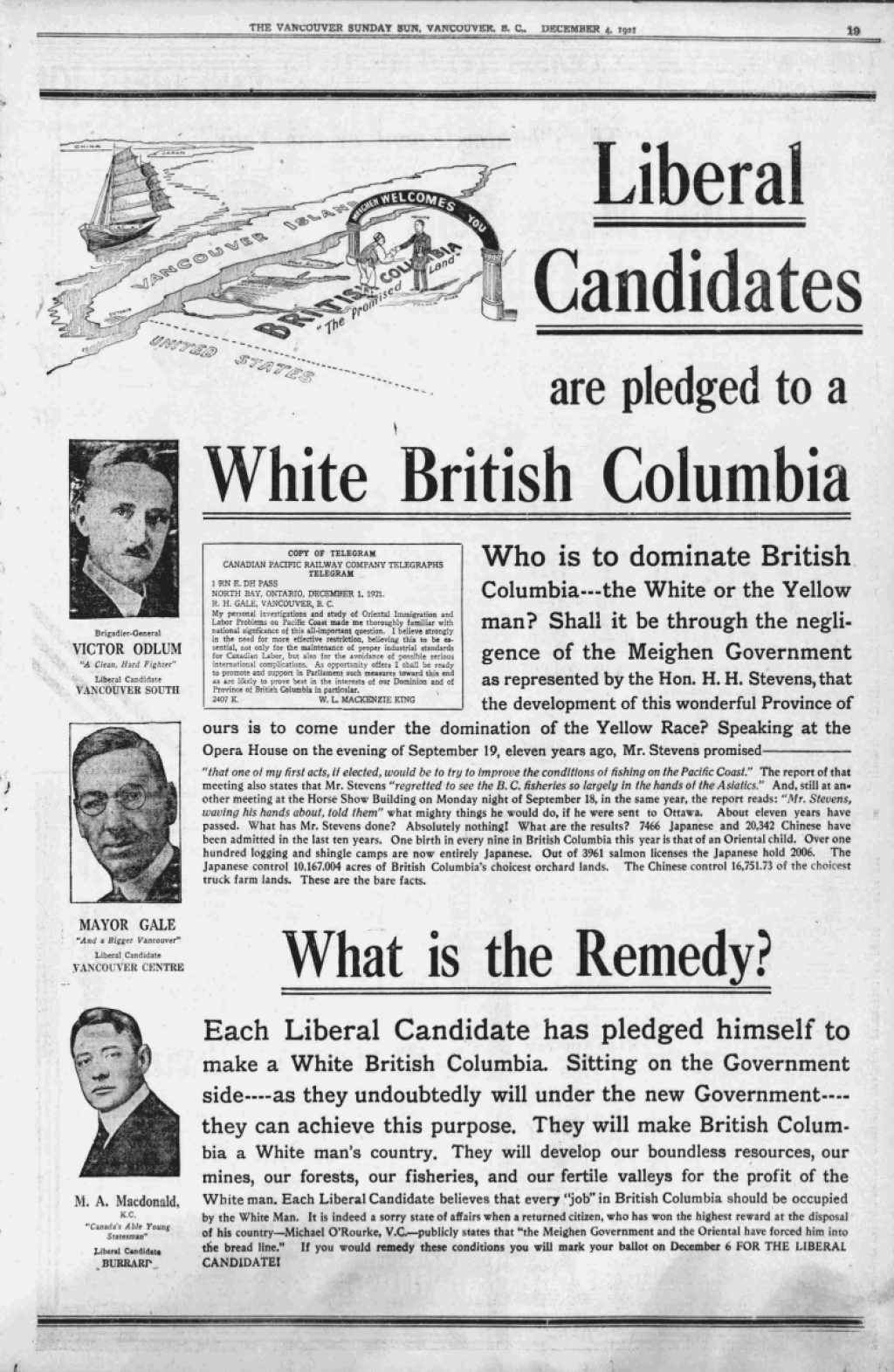

In Vancouver, the Board of Trade declared in 1921 that Asian Canadian landholding should be restricted and that they “would do everything in our power to retain British Columbia for our own people,” by which they meant white people.

The Victoria Chamber of Commerce created a “Committee on Oriental Aggression” that year. The committee submitted its report in November, recommending a complete ban on immigration from Asia, the enforcement of health and sanitary standards in Chinese communities, a ban on Asian Canadian ownership of property, and segregation of Chinese students in public schools. J. O. Cameron, a US timber baron and committee member, told the Chamber “the present system of public education was encouraging social equality and should be remedied.”

Media and culture opportunistically catered to and enflamed racism and xenophobia. The Vancouver Daily World began a concerted anti-Asian campaign led by journalist J. S. Cowper. The Vancouver Sun joined in, publishing the racist novel The Writing on the Wall by H. Glynn-Ward. A new racist newspaper, Danger: The Anti- Asiatic Weekly, had a brief but destructive existence.

On August 16, 1921, trade unions, veterans groups, and business associations gathered at the Vancouver Labour Hall to re-create the Asiatic Exclusion League (AEL) of Canada. Its goal was to create a ‘White Canada’ through “a campaign of education and organization to meet the dangers confronting the population of British Columbia from the ever encroaching industrial and commercial pursuits of Asiatics.”

A month later, the Vancouver Board of Trade joined the AEL and called for the “ultimate total cessation of Oriental immigration,” as well as a prohibition on “further acquiring of lands in this province by Orientals.”

The provincial legislature joined the fray, passing a resolution demanding that the federal government “totally restrict the immigration of Asiatics into this Province, keeping in view the wishes of the people of British Columbia that this Province be reserved for people of the European race…”. A similar resolution passed in 1922.

The federal parliament appointed a fisheries commission in 1922 that included anti-Asian politicians A. W. Neill from Comox-Alberni and W. G. McQuarrie of New Westminster, who had demanded that “steps be taken toward restoring the fishery to white fishermen and Indians.”

It didn’t take long for McQuarrie and federal politician H. H. Stevens of Vancouver to amplify the backlash. In the spring of 1922, they introduced a non-binding resolution in parliament calling for an end to all Asian immigration to Canada. The May 8 resolution represented a well-organized drive for exclusion and found support among many members of the newly elected Liberal party. It was an ominous sign of things to come.

Confronting the Backlash

However, resistance to the crucible of white reaction also intensified.

The Japanese Labour Union

A delegation of this union protested the formation of the Asiatic Exclusion League in Vancouver at its offices in 1921. The union had been established in April 1920, after Japanese and Chinese workers joined with white workers to strike at a lumber mill in Swanson Bay, located on the central coast of BC, for better wages and working conditions.

Soon after, workers who participated in this strike, together with local activists Sukuzi Etsu and Umezuki Takaichi, formed the Canadian Japanese Labour Union (Kanada Nihonjin Rodo Kumiai). Feminist and community activist Tamura Toshiko was an important supporter of the union.

The union fought for the rights of workers in the forest and fishing industries as well as for day labourers and laundry workers. It sponsored the labour papers, Rodo Shuho (Labour Weekly) and the Nikkan Minshu (Daily People and later became the Japanese Camp and Millworkers’ Union.

Chinese Students Strike

In 1922-3, the Victoria Chinese community organized a students’ strike in opposition to the Victoria School Board’s order to segregate all Chinese students in Chinese-only schools, including those who spoke English as their first or only language. According to the board, segregation was necessary to provide special instruction in English to the Chinese, but racism was the real reason; as one trustee explained, “the mixture of white and Chinese students in the public school is abominable.”

A youth organization called the Chinese Canadian Club (CCC) initiated the strike, working with the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association to mobilize the entire Chinese community behind their cause. Their rallies drew thousands of people and raised thousands of dollars in Vancouver and Victoria, organizing enough support that two trustees opposed to segregation were elected to the Victoria school board.

CCC president Joe Hope noted many years later that the students’ were able to build the solidarity of the entire Chinese community, bringing together people of diverse origins, languages, and interests, as well as competing associations and rival political parties. This unity enabled the community to survive the challenges of the Chinese Exclusion Act.

Canada-wide fight against the Exclusion Act

The 1922 parliamentary resolution calling for an end to all Asian immigration galvanized Chinese communities across the country. The Liberal government (replacing the Conservatives in late 1921) focused its energies on pursuing Chinese exclusion while finding other solutions to limit Japanese and South Asian immigration. Chinese government representatives in Canada shared this information with Chinese Canadian leaders and communities began to mobilize.

Many organizations and sectors of society rallied to organize opposition. Chinese Benevolent Associations played a leading role, communicating details of the proposed Exclusion Act and urging members to unite to defend their rights. Associations were set up in cities and small towns across Canada, collecting funds and arranging demonstrations. Trade unions such as the Chinese Labor Association of Vancouver, the Chinese Shingle Workers’ Federation, and the Chinese Produce Sellers group responded publicly to the proposed Exclusion Act with a counter- proposal. Protest only mounted going into 1923.

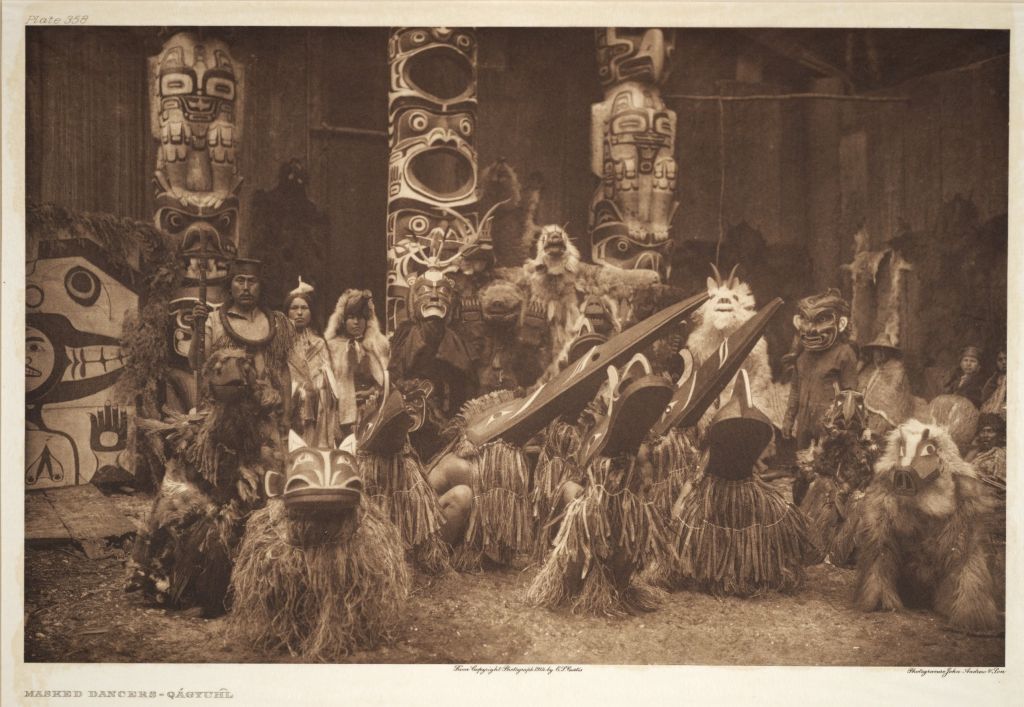

Anti-Indigenous Racism

The rise of the racist coalition in “British Columbia” and the pressure to pass a Chinese Exclusion Act coincided with the attempt on the part of the federal government to reinforce state control over Indigenous peoples and social movements. As deputy superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA), Duncan Campbell Scott came to play a powerful role as a bureaucratic steward of white supremacy. His specific goal was to overcome Indigenous resistance to Canada’s genocidal policies of seizing their lands and destroying their communities.

In the face of ongoing Indigenous resistance to residential schools, for example, Scott advocated for parliament to amend the Indian Act in 1920 so that it became compulsory for all Indigenous children to attend the schools. Thousands would die there, their bodies were not returned to their families, and today are being found in unmarked graves. The residential school system remains a travesty that continues to haunt survivors and families, directly and through intergenerational trauma, as shown by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

At the same time, Scott oversaw stricter enforcement and adherence to laws banning the Potlatch. This amendment to the Indian Act was introduced in 1884 but many First Nations continued the tradition, particularly on the west coast. At the behest of DIA agents, Scott urged a crackdown to reinforce the government’s policy of forcing assimilation by attacking Indigenous institutions. Resistance to such policies never ended.

Six Nations Confront the State

In 1920, Scott and the DIA began a crackdown against The Six Nations of Grand River. Taking advantage of divisions in the community that had arisen during the war (see chapter 1), Scott began to undermine the traditional Confederacy Council headed at the time by Deskaheh (Levi General).

Deskaheh had become speaker for the Six Nations Council after the DIA tried to impose military conscription. He openly defied Canadian control, traveling to London, England on a Six Nations passport to ask the British monarchy to support Haudenausaunee sovereignty. Scott was determined to get rid of Deskaheh and replace the Confederacy Council (composed of hereditary chiefs often appointed by clan mothers) with an elected band council mandated by the Indian Act.

In late 1922, during an arbitration process, the RCMP raided Six Nations territory and shot one of their warriors. Speaking to the momentous nature of the transgression, Deskaheh wrote at the time that it was unprecedented for the government to send mounted police to their land. “They had no right to shoot any Indian. They shot him five times…is this what you call a protection according to our treaty.” In response, Deskaheh and the Confederacy Council decided they had no choice but to appeal to the newly formed League of Nations to recognize their status as a sovereign nation.

With the Six Nations rising in defense of their sovereignty while Chinese communities fought hard against racist exclusion, 1923 was shaping up to be a year that would determine the course of Canadian history for decades to come.