One hundred years ago—July 1, 1923—the Canadian government passed “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration.” Known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was an overtly racist law prohibiting the arrival of newcomers from China. It also required all people of Chinese heritage, including the Canadian-born, to register with the federal government in order to stay in the country. Chinese Canadian communities across the country mobilized to lobby against the act but in the end their efforts failed to stop its passage. Thus, July 1 came to be known as “Humiliation Day” for many Chinese Canadians.

On the 100-year anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Monitor is releasing a series analysing the context in which the Act passed, resistance to the law, and its historical legacy. These articles are a serialization of the booklet 1923: Challenging Racism Past & Present, which you can read in full at https://challengingracism.ca/

World War I began in the summer of 1914. The government introduced the repressive War Measures Act that same year, which led to the unjust detainment and incarceration of Ukrainians and other ethnic groups labeled as ‘subversives.’

Initially, large numbers of white men enlisted, creating labour shortages at home. Indigenous, Black, and other racialized communities faced systemic discrimination in recruitment policies, limiting their participation in the war. However, many persisted in finding ways to circumvent racist policies, such as through the formation of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, an all-Black labour corps. Many racialized soldiers who went to Europe and survived returned with a renewed determination to challenge racism.

Challenging Racism in Recruitment

Indigenous peoples in Canada responded in complex ways to the onset of war in July 1914. Initially, the war department was reluctant to recruit First Nations men because “the Germans might refuse to extend to them the privileges of civilized warfare.” By late 1915, however, recruiters began to enlist First Nations men, with many joining the Canadian Expeditionary Force.

Haudenosaunee (Six Nations) Confederacy

In response to the Borden government’s campaign to raise war funds, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy Council asserted that their nations “[did] not belong to Canada and wish[ed] to make their contributions direct[ly] . . . as a token of the alliance existing between the Six Nations and the British Crown.” The Confederacy Council considered itself to be in a treaty relationship with Britain that predated the formation of the Canadian state. As such, the council would maintain a neutral stance toward the war until King George V made a formal request for assistance.

The Confederacy allowed individual members to enlist, and many did. A Mohawk woman, Edith Monture, became the first Indigenous woman in Canada to become a registered nurse and served in Europe during the war. Because wartime nurses were also awarded the franchise, she was also the first Indigenous woman able to vote, over four decades before Indigenous people were enfranchised. After the war ended, Monture returned to Six Nations Reserve where she worked in a local hospital and fought for better health care for her community. A Patriotic League to support troops abroad brought other Haudenosaunee women to the fore. At the same time, differing views of the war promoted divisions within the

Confederacy, including disagreement over the merits of an elected band council versus hereditary leadership.

The introduction of conscription in 1917 provoked widespread resistance by First Nations. The Port Simpson Band in British Columbia petitioned against the Military Service Act, stating, “at no time have our Indians had any say in the making of the laws of Canada.” Continuing resistance to conscription finally forced the government to pass an order-in-council, PC 111, exempting First Nations from military duty. Nevertheless, thousands of First Nations men went to war. Many felt they were maltreated upon their return to Canada and excluded from the benefits that white soldiers received.

Asian Canadians

Asian Canadian communities also faced major impediments to enlisting. The Japanese Canadian Association formed a company of 227 volunteers that began training in Vancouver. When the Association made a formal offer to form a battalion, Militia Headquarters flatly refused them on the grounds that integration with white soldiers would be difficult. Canadian military officers also feared enlistment of Japanese Canadian soldiers might reinforce their demand for the right to vote, a right the BC government had denied them since 1895. Despite this setback, over 200 Japanese Canadians traveled outside BC to enlist. Fifty-four died in battle and 92 were wounded, with many being decorated for bravery, including Masumi Mitsui, who would later lead the movement for enfranchisement. Under conscription, PC 111 also exempted Japanese Canadians from service.

Chinese Canadians who hoped to enlist in BC were also turned away. Nevertheless, a number traveled to Alberta or other provinces to enlist, including Frederick Lee and brothers Wee Tan and Wee Hong Louie from the Shuswap region in the interior of the province.

A few men of South Asian heritage were able to enlist but in general the colour bar was strictly enforced both because of racism and fear that anti- colonial sentiment might lead to South Asian troops turning their guns on the British.

Black Forces

“They fought their country to fight for their country”. – Senator Wanda Bernard, presentation at the National Apology, July 9, 2022, Truro, Nova Scotia.

Former senator and author Calvin W. Ruck describes the landscape of war mobilization for Black communities during 1917: “Throughout the country, from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, large numbers of Black volunteers were being rejected strictly on the basis of our colour.” Yet the Borden government claimed that “no outright ban on Black enlistment existed” and that “commanding officers controlled the selection without interference from headquarters.” Even if men enlisted, some were not allowed to serve. Some Black volunteers were discharged when white soldiers refused to serve with them. In some cases, the reason noted was that they were “undesirable.” Colonel Ogilvie, the officer commanding Military District 11 in Victoria, BC reported in 1915 that “several cases of coloured applicants have been reported on by Officers Commanding units and the universal opinion is that if this were allowed it would do much harm, as white men here will not serve in the same ranks with negros [sic] or coloured persons.”

No. 2 Construction Battalion, Canadian Expeditionary Force

By 1916 the Allied leadership was growing alarmed at the blood bath that was taking place on the battlefields of France and Belgium. Casualties were reaching staggering proportions and reinforcements were almost non-existent. On May 11, 1916, the British War Office decided to accept an all-Black labour corps, the No. 2 Construction Battalion.

Despite the easing of racist restrictions to enlistment, racist attitudes were prevalent and unrelenting. Those who did enlist were often derided by the medical staff assigned to examine them. The first and only Black battalion in Canadian military history, No. 2 Construction Battalion, which included five men from British Columbia, was segregated during its maiden voyage to England in order to avoid “offending the

susceptibility of other [white] troops”. The battalion proved a disciplined unit, put aside the overt racism, and produced double the output of other comparable units while living in segregated camps without proper medical care, rations or equipment.

Demobilization was an equally discriminatory process, dictated by race, rank, and class. Skilled white officers were not only the first to arrive back in Canada but were also greeted with nation-wide celebrations and fanfare, unlike racialized soldiers. Black soldiers waiting to come home endured anger and frustration as delays in demobilization dragged on. It would not have taken long for them to realize that the racism, segregation, and discrimination they experienced before and during the war was waiting for them upon their return.

White Women Win the Vote

Women won the vote in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta in 1916 and in Ontario the following year. Federally, a limited franchise began during the war (see poster). In 1917, white women in British Columbia won the right to vote after a referendum and provincial election that saw the Liberal Party replace the Conservatives. Interestingly, only men voted in the referendum on whether women should get the vote, casting 43,619 in favour and 18,604 opposed.

This was an important victory for white women, but also posed a question: Was the referendum a reflection of an enlightened male constituency or a quest for racial solidary? White women won the vote in many provinces during and after the war as political elites sought to expand their voting base. Yet their platforms were expressly racist, as they portrayed themselves as the ‘mothers of the race’ in contrast to Eastern European men (who could vote) and Asian Canadians and First Nations (who could not).

Organizing during War

Racialized communities continued their organizing efforts during the war as they faced a multitude of challenges.

The Allied Tribes of British Columbia

The increasing number of white settlers in BC severely affected the ways of life and subsistence of Indigenous Nations as they struggled to obtain land for agriculture and waters for fishing. Growing disputes over land, reductions in the size of reserves, denial of the Douglas Treaties, and the potlatch ban resulted in an upsurge in Indigenous organizing. In the spring of 1916, a delegation of the Interior Tribes of BC and the Nishga Land Committee traveled to Ottawa to press home their demand for a judicial decision on aboriginal title, as demanded in the Nishga Petition.

British colonial authorities refused to consider a legal case as long as the Mckenna-McBride Commission (MMC) was operating. As a result, representatives from a majority of Nations met in Vancouver to form the Allied Tribes of British Columbia. The Allied Tribes denounced the MMC, supported the Nishga Petition, and demanded reserves of 160 acres per capita, full compensation for alienated lands, and recognition of Aboriginal title.

Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) (1914-1921)

Founded by Jamaican-born Marcus Garvey in 1914, the UNIA was part of a global movement to unite, empower, and improve the lives of people of African descent. The movement newspaper, “Negro World”, said to have a readership of 200,000, was a key organizing tool and central to the movement’s success. The UNIA paid attention to Black women’s labour and financial needs, starting the Black Cross Nurses program, which helped Black women find employment outside domestic and factory work.

A dynamic if controversial figure, Garvey first visited Canada in 1917. Within a few years, the UNIA had nearly 5000 members in 32 divisions in Nova Scotia, Quebec, Ontario, Manitoba, Alberta, and British Columbia. The UNIA sponsored the construction of several community centres, including in Montreal and Glace Bay, NS – the latter being the only original hall still in existence. The Montreal Liberty Hall was an important centre, providing education and supporting social, cultural, and economic needs.

The vast majority of Canadian members were West Indian immigrants, who brought a strong pan-African consciousness to the leadership of the UNIA. The Universal Negro Improvement Association was designated a national historic event in 2018. Today, the Glace Bay UNIA Community Hall runs a cultural museum.

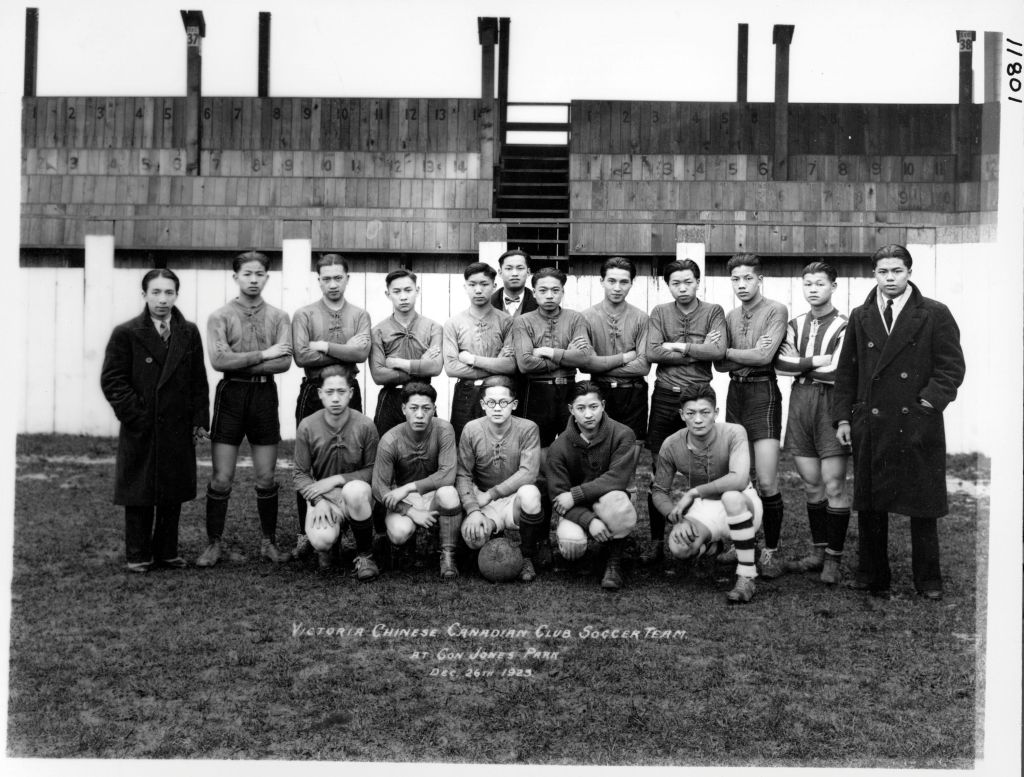

Chinese Canadian Club

Established in 1914 in Vancouver and Victoria, the Chinese Canadian Club was the first group to publicly use the term ‘Chinese Canadian.’ Originally a young men’s social club, within a few years it became politically active, unsuccessfully campaigning for the right to vote for Canadian-born and veteran Chinese people. The Chinese Canadian-born generation would play increasingly important roles in leading the fight against white supremacy in the years to come.

Previously, migrants from China coming to Canada did not think of themselves as members of the same group; they spoke different languages and identified with their home counties or places of origin. However, by the 1910s, the common experience of racist oppression led diverse communities to develop a shared identity as Chinese. They built collective organizations to organize self-defence and provide mutual aid.

Most important of these organizations were the Chinese Benevolent Associations (CBAs) of the major cities, which were umbrella organizations that brought together different associations. Victoria’s Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association, the original CBA, functioned as a Chinese-controlled local government as it arbitrated disputes in the community, provided free services including a public school, assisted those in trouble with white authorities, and protested racist measures.

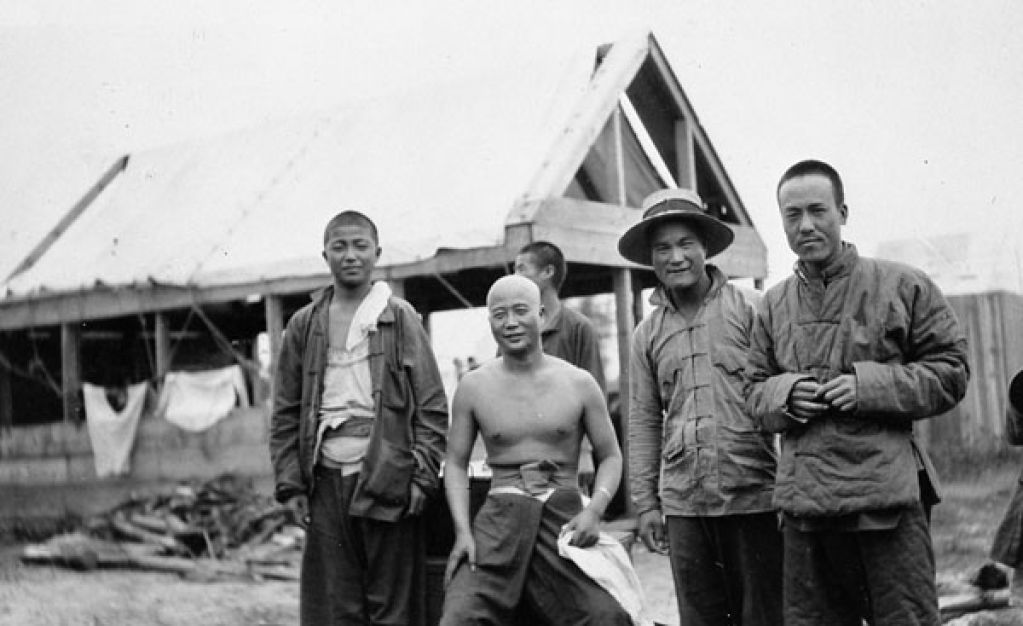

The Colour of War

Over 120,000 labourers from China joined the war in Europe in 1917. Of these, approximately 80,000 traveled from China to Europe and back again via Canada. Their treatment while in Canada—kept in quarantined camps for weeks and transported in sealed rail cars across the country—was hardly what one might have expected given their status as valuable allies in the war effort. As one historian put it, “Canadians, as a whole, treated the Chinese in Canada badly and treated the Chinese labourers on their way to France even worse.”

They were part of a huge contingent of racialized troops and labour battalions that fought in various fronts of the war in Europe, Africa, or the Middle East. This included more than 200,000 African Americans; over 15,000 troops from the Caribbean; over a million from Africa; approximately 1.4 million from the Indian sub-continent; more than 90,000 from Vietnam and Cambodia; and 120,000 from China.

Of the estimated four million or more participants, racialized as non-white in a variety of ways, the vast majority were men and tens of thousands perished. Racialized women also participated in the war, some as nurses and others, particularly in Africa, as carriers or transport workers for supplies for the opposing armies. These included the imperial powers of Britain, France, Russia, Italy, and Japan, who warred against Germany, the Austro-Hungarian empire, and the Ottoman empire in 1914. The United States joined the war in the spring of 1917, while Russia withdrew after the 1917 revolution.

At least nine million people lost their lives in this war, and its ramifications were felt long after. In the end, the colour of war was red – the common colour of the blood shed by all men and women, including huge numbers of civilians, who were sacrificed life or limb in this dreadful conflict.