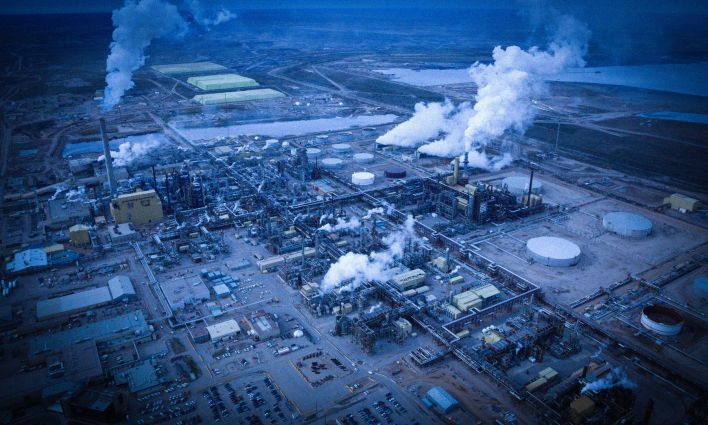

The past few years have seen what could be the beginning of a serious reorganization of global trade. Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the United States' mounting conflict with China, the post-COVID recovery—these elements have combined to create mounting tensions in international trade.

These tensions are further aggravated by climate change. Powerful countries are adopting subsidies and tariffs to meet their climate change goals, spurring their own green industries and reorganizing supply chains around regional allies.

In this context, at the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos this past January, where the world’s super rich meet annually with politicians and business leaders, 50 trade ministers from across the globe launched the new Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate.

Co-led by trade ministers from Ecuador, the EU, Kenya, and New Zealand, the Coalition aims to promote “cooperation, inclusivity, leadership, and transparency” in climate change mitigation and adaptation through fostering an “open international economic system.”

While the Coalition represents a high-level of political engagement, it is rife with contradictions. The US—a member of the Coalition—has already authorized $369 billion USD in subsidies to green its economy through its Inflation Reduction Act.

European Union countries , recently proposed 270 billion euros in subsidies for their own green transition, and the EU is developing a carbon border adjustment plan that would place tariffs on carbon intensive imports from other countries–a move criticized by China, India, and others as unfair protectionism. Not only is the EU trade commissioner a co-leader of the Coalition, but the individual trade ministers from 26 EU member countries make up nearly half of the Coalition partners.

Given the actions of the richest countries in the world, one might wonder why they talk about open trade as being either desirable or possible for addressing the major climate demands ahead. What politics lies behind this contradiction?

The World Trade Organization as Climate Hero?

To start, the main goal of the Coalition is likely less about achieving actual free trade than about defending the reputation of trade in a world where climate change has called into question the entire global economy.

Defending international trade has often fallen on the shoulders of the World Trade Organization (WTO)—the top intergovernmental trade organization with 164 member states. Long criticized by social movements and Southern governments for being an institution whose rules unevenly benefit rich countries and transnational corporations, the WTO has sought to promote itself as a multilateral body aimed at “inclusive” and “sustainable” trade for all.

Climate change is at the forefront of the WTO’s sustainability agenda, and the organization has highlighted its ongoing negotiations aimed at removing subsidies on fossil fuels, illegal fishing, and plastics, as well as removing trade barriers on green technology and products.

Despite these efforts, making the case that the expansion of trade can be harmonized with the demands of climate change—which requires a rapid reduction in emissions associated with globalized production, transportation, and consumption—has not been easy. The WTO’s World Trade Report 2022 estimates that the carbon emissions embedded in world exports in 2018 accounted for 30 percent of the world’s total.

While ultimately confident that trade sparks green innovation and facilitates its adoption, the WTO concedes that “paradoxically, economic progress is both the cause of and the solution to the climate crisis.”

It is within this context that the new Coalition of Trade Ministers on Climate emerged, initially out of discussions at the WTO in Geneva. The Coalition explicitly supports WTO initiatives, and WTO Director General, Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala attended its launch, calling it “historic” and stating it “sends a very strong message that trade — rather than being seen only as part of the problem — is also part of the solution.”

Confronting Unilateralism

Wealthy countries are not the only members of the Coalition, which involves countries from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, including ones that are particularly vulnerable to climate change like Vanuatu, the Maldives, and Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and is co-led by Ecuador and Kenya.

To member-states from the Global South, the Coalition represents a possible mechanism for confronting the actions of powerful members—whose unilateral subsidization will give a green growth advantage to already-rich countries, leaving middle and low income ones behind in the transition.

With this in mind, the Coalition’s founding statement affirms the importance of “inclusive international cooperation that includes a diversity of countries from different regions at different levels of development,” and calls for “the diffusion, development, accessibility and uptake of goods, services and technologies that support climate mitigation and adaptation in both developed and developing countries.”

As the Coalition develops its agenda, with its next meeting scheduled alongside the WTO Ministerial Conference in 2024, it remains to be seen what these statements will amount to. By linking trade policy to climate change, Southern members likely hope for firmer commitments on green finance and technology sharing—echoing demands at COP27 for $100 billion in annual funding to deliver rapid climate investment and action in the Global South.

The big issue that will almost certainly not go away is the role of green subsidies, underpinning the efforts not just of Western countries, but economic giants in the Global South. China now dominates the world’s solar panel industry after decades of subsidizing its solar industry. Recently, China announced plans to eliminate these subsidies, while at the same time acknowledging it had built up a backlog of over $62 billion USD in subsidies to renewable industries that has still to be paid out.

While free trade economists claim subsidies distort markets and swell government debt, governments are set to ramp them up as rich countries pursue the “green subsidy race.” The real question is whether low and middle income countries will be left further behind. Will the Coalition become a global trade talk-shop, where rich countries proclaim their dedication to “open” markets while subsidizing their own industries?

Or will it become a place where governments take genuine steps to support the diffusion and development of green technology through “inclusive international cooperation,” as the Coalition’s lofty goals state, and Southern partners no doubt aspire to?

For rich countries, it is less clear what these statements will mean—or if they will remain, as is often the case in global accords, just statements.