In the aftermath of the USMCA negotiations, the Trudeau government chalked up two significant “wins” for environmental protection and Canadian sovereignty: the elimination of investor state dispute settlement (ISDS), at least in the Canada-U.S. context, and the disappearance of NAFTA’s so-called proportionality clause in the energy chapter.

The latter is particularly surprising given that in the run-up to the negotiations neither the U.S. nor Canadian governments indicated that proportionality would be on the agenda. This begs the question: why was this undeniably regressive feature of NAFTA removed? And what does this mean for Canada’s energy and climate future?

Proportionality in a petro-state

Canada is a petro-state. We have the third largest crude oil reserves and are the fifth largest exporter of oil and gas in the world. These exports are largely destined to the U.S. and have steadily increased over time. This trend has been driven by the bilateral integration of energy markets, facilitated by free trade agreements.

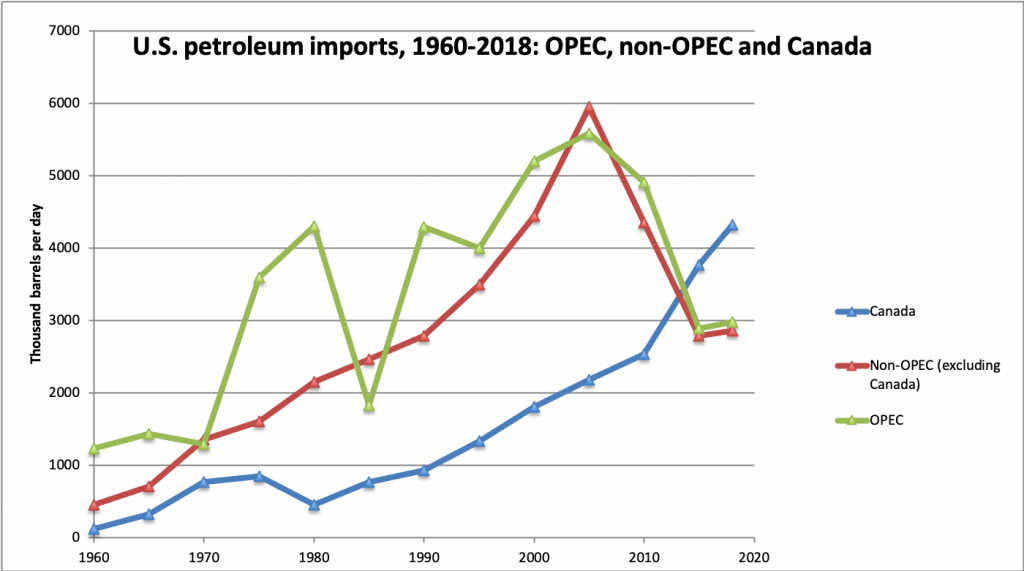

The graph below shows the sources of petroleum imports to the United States [1]. The Canada-United States free trade agreement was negotiated the 1980s and this period also saw the beginning of sustained growth in Canadian petroleum imports. In 2014, Canadian imports overtook those from OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries). While this graph indicates correlation not causation, the oil industry is not shy about crediting NAFTA for increasing oil exports to the United States.

The proportionality clause goes by a couple different names: Foreign Affairs Minister Chrystia Freeland calls it the “energy ratchet clause,” while the oil industry prefers the “good neighbor clause.” The proportionality clause was first negotiated in the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement and later included in NAFTA. The clause requires Canada to maintain a consistent share of energy exports to the U.S. as a proportion of domestic supply based on a three-year average. The proportionality clause effectively only applies to Canada, as Mexico negotiated an exclusion and the U.S. is a net energy importer from Canada. Although the clause has never been invoked, oil-sands giant Cenovus Energy Inc. recently called on the Albertan government to temporarily cut production in the oil sands.

I won’t dive into the weeds on how proportionality was born—Gordon Laxer does a great job telling this story here—but the combined political power of the oil and gas industry and the bargaining power of the U.S. produced a clause that guaranteed the U.S. unrestricted access to Canadian oil and gas. As a result, proportionality has hung like a spectre over Canadian energy policy and helped lock Canada into a high carbon pathway that makes us a major exporter of carbon emissions.

Why has support for proportionality waned?

In 1993, before the ink on NAFTA was dry, the newly elected Chrétien government promised to remove proportionality from NAFTA. Two months later, the agreement was signed and the energy chapter remained unchanged. Opposition from the U.S. government and the North American energy industry buried Chrétien’s pledge. Why was the Trudeau government successful this time? There are three key factors.

1. “It’s the economy, stupid.” The energy landscape in North America has changed drastically since the negotiation of the original NAFTA. The shale boom has meant U.S. natural gas and oil production have skyrocketed over the last decade. Although the U.S. is less reliant on Canadian oil and gas imports as a result, Canada remains the largest source of U.S. crude oil imports, with our exports exceeding imports by a large margin. But Canada is also the largest importer of U.S. crude oil exports and Eastern Canada has become an important market for U.S. shale gas. In other words, while Canada is still the most affected, proportionality now cuts both ways.

2. Corporate interests aligned. Neither the Canadian nor American oil industries appear to mind that proportionality is gone. Both the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) and its American counterpart, the American Petroleum Institute (API), had their list of asks met in the NAFTA renegotiation [2]. They both welcome new language restricting “unnecessarily burdensome” regulations affecting the oil and gas sector (e.g., administrative delays in the approval processes for oil infrastructure, pipelines and major projects). API in particular has been very vocal about the positive outcome of the agreement.

As evidence of the political power of the oil and gas lobby, the industry is one of a handful of sectors in Mexico to retain access to ISDS. Keeping the controversial dispute mechanism in place for their Mexican investments was a “higher priority” than in Canada, especially since Mexico opened its markets in 2013 to foreign companies. But on the issue of proportionality, CAPP Vice-President Nick Schultz said that it doesn’t mean much. Neither industry in Canada nor the U.S. needed proportionality to ensure the continued integration of energy markets.

3. It was a bargaining chip. The elimination of the proportionality clause has made other tough pills easier to swallow for Canada, like opening dairy markets to the U.S., extending monopoly protections for brand-name drugs and accepting continued tariffs on key Canadian products (i.e., steel, aluminum and forest products), to name a few. The pointed rhetoric coming from the federal government after the negotiations that the proportionality clause “impinged” on Canada’s sovereignty is indicative of this rationale. Although the U.S. government decided not to base the USMCA energy chapter on NAFTA, scrapping proportionality didn’t cost the U.S. or corporate interests much, and the Canadian government could claim a win.

So where does the USMCA leave us? The deal continues to bind North America together in an integrated fossil fuel market. This industry has disastrous implications for the climate. Others have shown how much oil and gas needs to stay in the ground for us to avoid catastrophic climate change. The oil and gas sector is the highest emitting sector in Canada, largely concentrated in Alberta. Despite Alberta’s promise to cap emissions at 100 million tonnes, a forecast by the Canadian Energy Research Institute suggests they will exceed this cap in 2030.

Given this reality, the USMCA falls far short of the agreement we need. So while we can take a moment to celebrate the removal of the proportionality clause, there is significant work to be done if we are to meet our climate targets.

The author would like to thank Sujata Dey, Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood and Scott Sinclair for providing invaluable comments and insights.

Endnotes

[1] Data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) Monthly Energy Review.

[2] See CAPP and API documents respectively; trilateral statements from oil and gas industry available here and here.

Amy Janzwood is a PhD Candidate in Political Science and Environmental Studies at the University of Toronto and a Research Associate at the Munk School’s Environmental Governance Lab. Follow her on Twitter @amyjanzwood.