The Fraser Institute has a new report warning Ontario could become the next Greece or California because of the size of its debt.

Of course we know Ontario is not Greece or California, and such comparisons are disingenuous.

But it is possible that Ontario could find itself in a similar mess if it follows the Fraser Institute’s standard issue prescription for government financial management: more public spending cuts, more public sector layoffs, and more tax cuts.

Theoretically, Ontario could cut public spending even more than it already has. It could fire doctors and nurses, teachers and cops. It could close down hospitals, shut down schools, close child care centres.

It could ignore the at least 20,000 Ontarians who protested public sector cuts outside of the Liberal leadership convention just last Saturday.

It could ignore the latest Statistics Canada data showing Ontario has the second-worst levels of income inequality in Canada.

The austerity experiment has been waged in several European Union countries: Massive cuts in government spending for four years drove Greece, Spain, Portugal and Ireland into full-scale economic depression. Meanwhile, the U.K. is struggling to get off its austerity treadmill, despite the less than stellar results there.

Ontario could pretend that more of the same – cutbacks – will yield different results than it has already in Europe. But even the chief economist of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), Oliver Blanchard, has come out saying Europe went too far with austerity measures.

As for California, CCPA Economist Hugh Mackenzie says: "It's suffering primarily from the kind of policies the Fraser Institute advocates: cutting and freezing taxes when it doesn't make any sense to do so. Even the most superficial reading of the California experience points to the role that tax freezes, tax cuts and various propositions designed to limit the ability of California to meet its obligations."

Austerity poses a similar threat in Ontario, where more government cutbacks could lead to higher unemployment – including youth unemployment, which is already unacceptably high in Ontario.

Yes, Ontario did incur a deficit during the worst of the global economic crisis – due in part to dropping tax revenues, which always occurs during a recession, and aided by stimulus spending that helped prevent even more job losses.

The province launched into spending cuts before the economy had fully recovered, which hasn’t helped matters.

That said, Ontario’s deficit is on the mend more rapidly than expected. The Finance Minister says it’s already almost $3 billion less than his Fall 2012 prediction. Barring another economic downturn, Ontario’s deficit will be balanced by 2017 – quite possibly earlier, without needing to lay off workers, axe services and dangle more tax cuts in front of corporations.

The Fraser Institute’s shrill warnings notwithstanding, there is no need to press the panic button.

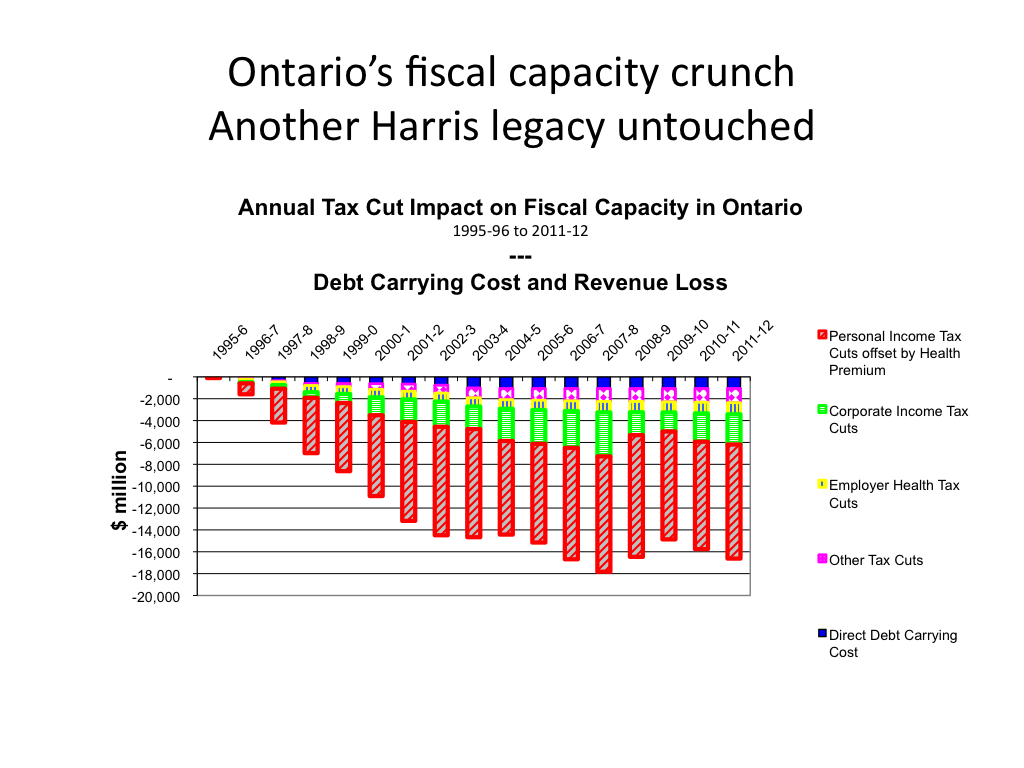

And the solution certainly isn’t more tax cuts – Ontario having given up a cumulative of $17 billion a year in tax revenues since the Mike Harris government implemented multiple rounds of tax cuts in the late-1990s. As you can see from this chart below, by Hugh Mackenzie, the real fiscal capacity crunch started in 1995-96 once Harris became Ontario’s premier.

The chart shows Ontario’s debt carrying costs and lost revenues since 1995-96 and calls into question the old fiscal ideas the Fraser Institute is heralding today. Those policy prescriptions didn’t work then and they’re not going to work now.

The 1990s called: They want their bad ideas back.

There is growing international consensus that the way out of the post-recession doldrums is to focus on economic growth through job creation and wage growth rather than debt and deficit reduction.

Job creation leads to a healthier economy, more people working, more people contributing in taxes – and it turns out that’s really great for deficit reduction. That, in fact, is the real lesson learned from the 1990s.

Ontario could also revisit the toll more than a decade of corporate and personal income tax cuts is taking on the province’s ability to remain resilient during inevitable economic downturns.

Perhaps it’s time to talk about the right balance of taxation to fireproof Ontario’s public services for the future, because the tax cut mentality of the 1990s is really so yesterday.

As for deficit hysteria in Ontario, it’s a bit like the boy who cried wolf. Ontario’s deficit can be managed without ravaging its public services.

This is an exceptional historical moment: interest rates are so low that Ontario could borrow money for decades at 2-3 per cent. That’s dirt cheap. It explains why the markets are not at all concerned about Ontario’s debt.

Most Ontarians are more concerned about their own jobs – they don’t name deficit reduction as a top concern. But they are worried about things like income inequality, which, by the way, the World Economic Forum says is the biggest threat out of 50 risks to global stability in 2013.

Repeat after me: Ontario is not Greece, nor should it make the same mistakes as Greece. It’s time to move on. It’s time to define our own agenda, a post-austerity agenda, and truly put Ontario on the path to economic recovery.