[Image: Twitter user @zittrain]

[Image: Twitter user @zittrain]

Perhaps it shouldn’t come as a shock that, as ends no longer come close to meeting, and as households reel under the strain of systems and employers that treat quality of life as an inconvenience, people are turning to “alternative funding models” to try and buy themselves some security.

Which means that moms-to-be in the U.S., without maternity leave benefits, are crowdfunding to try and literally buy some time with their newborns.

Or recent graduates, increasingly desperate at the prospect of paying off their debt loads while barely staying afloat in an insecure job market, are hoping that sympathetic friends and strangers might kick(start) in a few bucks to help out.

Crowdfunding may just be the new way to finance your personal life, explains Forbes magazine (assuming that maternity leave benefits and a nation of graduates unburdened by crippling student debt in an increasingly insecure job market is only about one’s personal life).

Indeed, on GoFundMe there are a reported total of 6,000 fundraising campaigns mentioning the words “maternity leave” or “childcare” (raising more than $9 million); between 2011-14, the number of campaigns mentioning “tuition” rose by a whopping 4,547%. After all, explains the cofounder of YouveGotFunds.com, “Why would college students want to graduate owing $150,000 plus in loans if they have family, friends and possibly community members who can help, enabling them to start their careers in a better place?”

But is monetizing the “kindness of strangers” a solution to the deeper problems that plague us? Or is just a way to reinforce the idea that if you can’t individually overcome systemic inequality you better be good at marketing yourself to a sympathetic audience of potential patrons?

“Well, what do you expect?” some may say. “You’re talking about the U.S. after all. In Canada we have a social safety net. Crowdfunding is just for extras.”

I mean, this is Canada.

Canada. Where, as a result of longstanding federal government inaction, Idle No More started a crowdfunding campaign to build homes in First Nations communities, explaining to prospective donors that a “healthy, productive and dignified home brings life and joy to families.”

Canada. Where legislative changes have also resulted in people having to seek alternative funding sources to launch constitutional challenges (which once could have been eligible for public funding through the Court Challenges Program).

But in a climate of “taxes are bad and program spending is worse”, perhaps public interest litigation, like human rights and dignity for Indigenous families and communities, has been redefined as an “extra”.

I have no problem with the idea of charitable giving in principle. People can—and do—give money to the various individuals, initiatives and causes they wish to support.

But the point is: it’s voluntary. Which means you give the amount you choose or can afford to support who or what you want. And because of this it’s inherently unreliable.

It may be nice (and depending on the size of the donation, it may get you lots of positive feedback and warm fuzzy feelings and newspaper headlines). It may be well intentioned. But none of that makes it fair.

Assuming fairness is what we’re after, of course.

Because in the world of charities it’s not those with the greatest amounts of money who give the largest proportion of it to causes they agree with (yes, even when taking branded wings of hospitals and university schools of management into consideration). It’s those who have the least who proportionately give the most. Which may be not so bad when we’re talking about boutique projects—but it’s an inherently inefficient way to fund a basic quality of life for all of us.

The most recent set of revelations of global tax avoidance by the wealthiest have underscored how collective responsibility without accountability can become a voluntary activity based on privilege. Where, as it has been said: wealth doesn’t trickle down; it gushes offshore.

There’s no question that our current model needs work—loopholes must be closed, and those who attempt to pay their way out of civic responsibility (along with those who profit from this lucrative industry of avoidance) must be held accountable.

We deserve a system that comes with full assurance that those who make the most, pay the most (even if their less glamorous, tax-based contribution doesn’t come with our slavish gratitude); one that efficiently and fairly ensures that we all contribute to and benefit from our collective investments in social and economic growth.

Not based on pet projects. Not based on fair-weather or self-serving (frequently tax deductible and definitely media friendly) generosity. Based on a sense of communal responsibility and the acknowledgement of how a better standard of living is good for all of us—not just those in a position to contribute the most to it (or to theirs’).

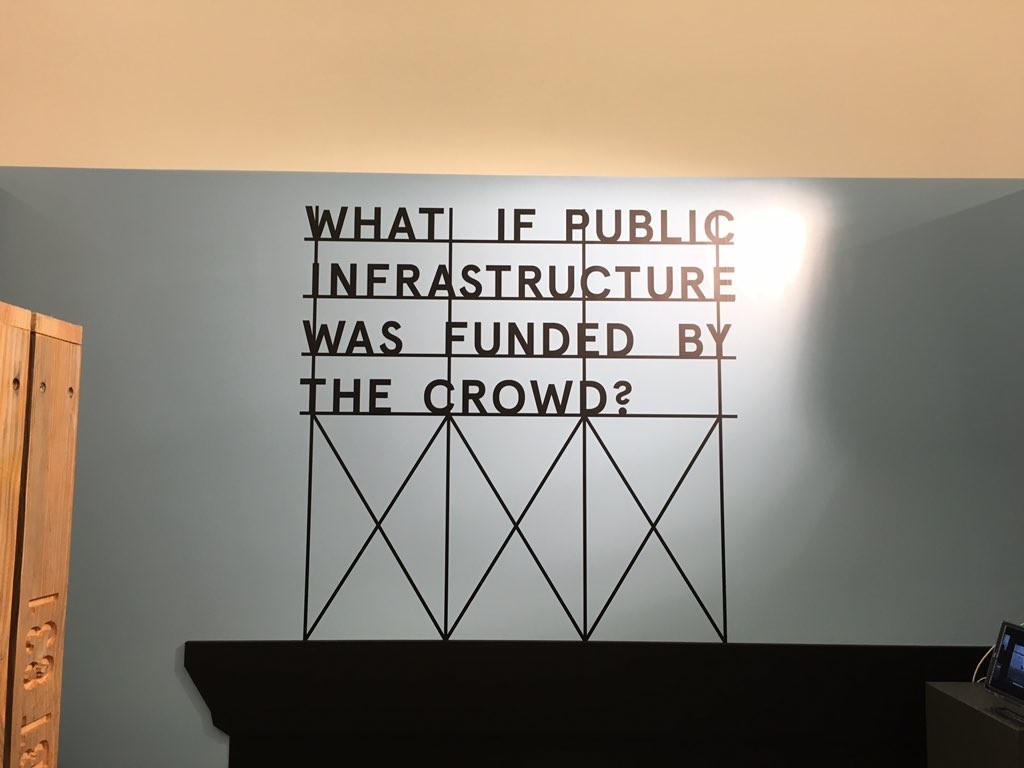

Progressive taxation is the original crowdfunding. When it comes to the public good, keep your standards high. And accept no substitutes.

Erika Shaker is Director of Education and Outreach at the CCPA. Follow Erika on Twitter @ErikaShaker.