There was a lot of talk in last night's debate about budgets, deficits, and program funding. So it seemed like a good time to look at the aggregate impact of the party platforms. In other words, let's talk about deficits.

The release of the Liberal platform came with much consternation about their updated deficit figures: they were higher, and absent the seemingly requisite commitment to balancing the books in four years (a promise that is apparently necessary for every party, irrespective of the likelihood of keeping this promise or how many cuts it would entail to do so).

When examining macroeconomic issues like government debt, it’s important to put these numbers into context. For example, a common but unhelpful trope is to equate government debt with family debt: obviously a family would be in dire straights if they had a $20 billion credit card bill coming due….but what’s missing from that scenario is that the family in question makes $2 trillion dollars a year (Canada’s GDP). Also often missing from the discussion is that when you’re a big as the federal government, the money required to eliminate the deficit must come from somewhere else in the economy, and it’s not an insignificant amount.

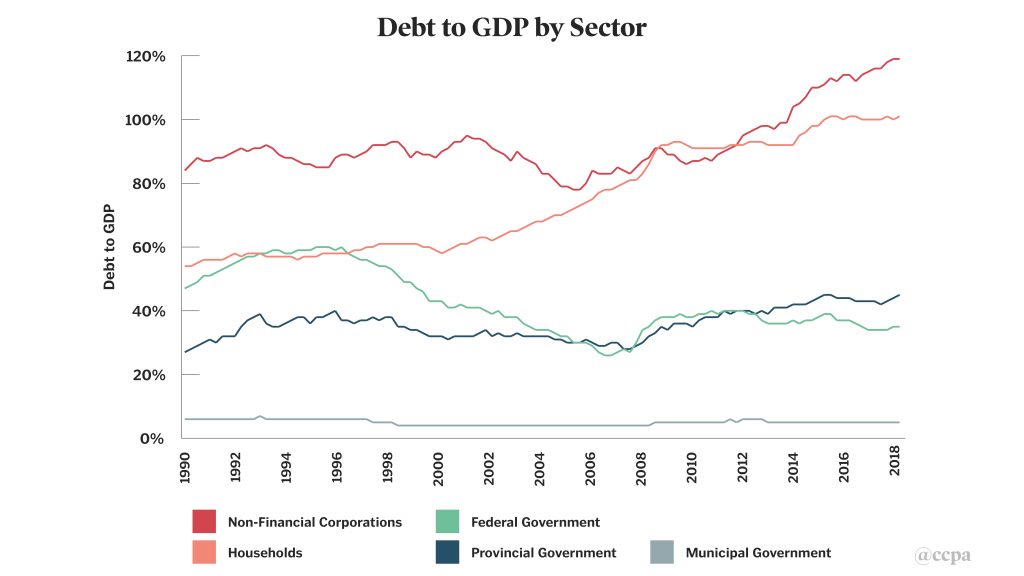

How does debt look across the various sectors of the Canadian economy? The federal government actually has the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio when compared to provincial debt, household debt, and corporate debt. Corporate debt has actually been increasing rapidly over the past five years, even as a percentage of GDP. So, if you’re worried about debt, you should be very concerned about corporations and households leveraging up, and much less concerned about the federal government’s debt (although given the current policy debate you wouldn’t know it).

The most helpful way to examine federal debt and deficits is not to look at them in isolation, instead they should be compared with other sectors, and put in the broader historical context.

Sources: StatCan tables 36-10-0580-01, 36-10-0103-01

Sources: StatCan tables 36-10-0580-01, 36-10-0103-01

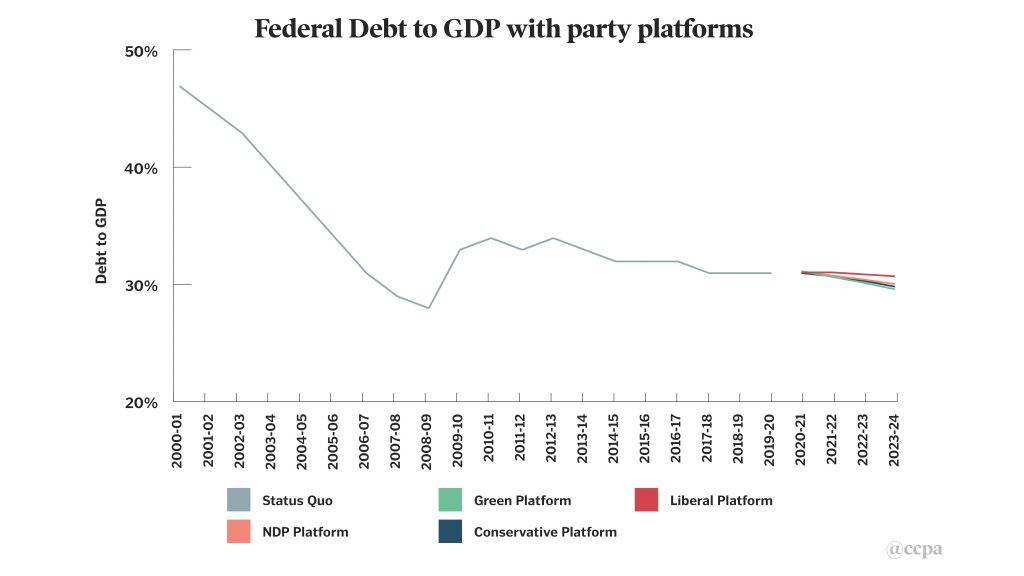

With respect to what the parties are planning (at least for the two that have released full platforms – I’ll update this as more platforms are released) and the federal debt-to-GDP ratio, an interesting picture emerges. The Canadian economy is large, and in the broader historical context what’s been proposed up to this point by both the Greens and the Liberals would result in quite small changes to the federal debt position. Relative to the size of our economy, their proposed deficits (and their impact on the federal debt) simply aren’t that big.

Then there is the perennial requirement that leaders commit to balancing the books over the four years, even though that rarely happens. Here’s why: these are the deficits of the sectors of the Canadian economy in 2018-19, the latest full fiscal year of data.

| Sector | Deficit in 2018-19 fiscal year |

| Corporate (non-banks) | -$163 billion |

| Households | -$79 billion |

| Provincial governments | -$61 billion |

| Federal government | -$31 billion |

The corporate sector has been taking out loan after loan, resulting in an astounding $163 billion deficit last year, much of which has found its way into shareholder payouts, corporate take-overs and real estate speculation, none of which are particularly economically productive. Households for their part are still taking out mortgage debt, the primarily contributor to that sector’s nearly $80 billion deficit last year. The (recently) higher provincial government debt levels are due in part to federal downloading. And at the bottom of the list, the federal government has increased its debt over the past year, but in comparison by much less.

Debt is neither good nor bad on its own. However, it comes with deeply engrained moral judgements which are then applied to government leaders who are deemed “virtuous” if they end up with a surplus but “immoral” if they run a deficit. But these moral judgements are only possible in the absence of context. Because it’s incredibly easy to balance the federal books – it’s just that Canadians would hate the consequences.

Easy ways to eliminate the federal deficit:

- We could cut the Canada Health Transfer to the provinces by $31 billion or 75%. New federal deficit: $0. New provincial deficit: $92 billion (up from $61 billion) as they attempt to compensate for the massive health care funding gap.

- We could increase corporate income taxes by 60%. Boom: federal deficit eliminated. Consequence: the new corporate deficit rises from $163 billion to $194 billion as they pay those new taxes.

- We could boost the GST from 5% to 8.75%. Bingo: federal books balanced. Consequence: household deficit rises from $79 billion to $110 billion as Canadians pony up on every purchase.

Ultimately, in a country with a growing economy and a growing population, new debt is manageable as long as it pays off more in GDP growth than it costs in interest. And with interest rates at almost record lows, that’s not too hard to do.

Editor's note: An earlier version of this article ran with a graph depicting federal debt to GDP levels for only the Green and Liberal parties. Following the full platform releases from the Conservative and NDP parties, the graph has been updated to include debt projections for all four parties.

David Macdonald is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter at @DavidMacCdn.

The CCPA has done extensive research and analysis on a wide range of federal policy issues, most notably through our annual Alternative Federal Budget. As we head towards the October 2019 federal election, we’ll be sharing our independent, non-partisan analysis and fact-checking of campaign promises and platforms from all the major parties.