In Ontario’s first-past-the-post electoral system, it’s not just a matter of counting votes. Here are a few things to think about that may help determine who wins—and who loses—on June 7:

Geography matters

Governments change when the same people vote differently, or when different people vote the same—but in a new place. This can happen when they move, and lots of Ontarians move, especially to booming centres like Milton, northwest of Toronto.

In the 2018 Ontario election, though, literally millions of voters are effectively moving because they’re ending up in new ridings due to redistribution. With 17 new ridings shoehorned into the electoral map, over 80 ridings have seen their boundaries change.

Many ridings have been dissolved entirely and their voters assigned to two or more neighbouring ridings.

Two of the new ridings are in the north, where Kenora-Rainy River and Timmins-James Bay have each been divided into two ridings. Some of the new ridings are in eastern Ontario. The lion’s share of new ridings is concentrated in fast-growing communities across the Greater Toronto Area (GTA).

From Durham to Niagara, many boundaries are changing significantly, throwing voters together in new combinations. In some cases, new boundaries may well affect which candidate ends up in Queen’s Park.

Vote efficiency matters

Pollsters report province-wide voter intentions as if the June 7 election will be one election. It isn’t—it’s 124 separate riding elections.

In our first-past-the-post voting system, votes for losing candidates do nothing to add to a party’s overall representation in the legislature and winning candidates who get more votes than they need in order to win do nothing for their party either. A party with an efficient vote is a party that converts votes into more winning ridings better than its opponents.

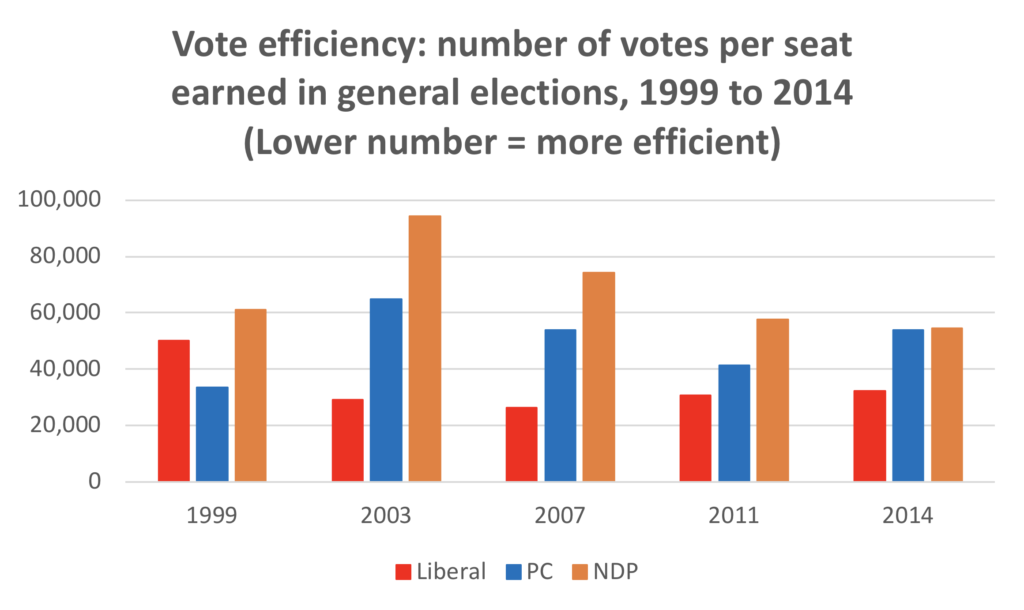

In the five elections since the Fewer Politicians Act, 1996, reduced the number of provincial ridings in Ontario, the party with the most efficient vote has won every time. In 2014, the Liberals won a seat for every 32,119 votes they received, while the PCs needed 53,795 and the New Democrats needed 54,504. The NDP’s vote efficiency has improved in each of the last three elections.

Small parties matter

Parties other than the three that currently hold seats in the legislature are often written off as “fringe,” but the Green Party of Ontario is working to change that.

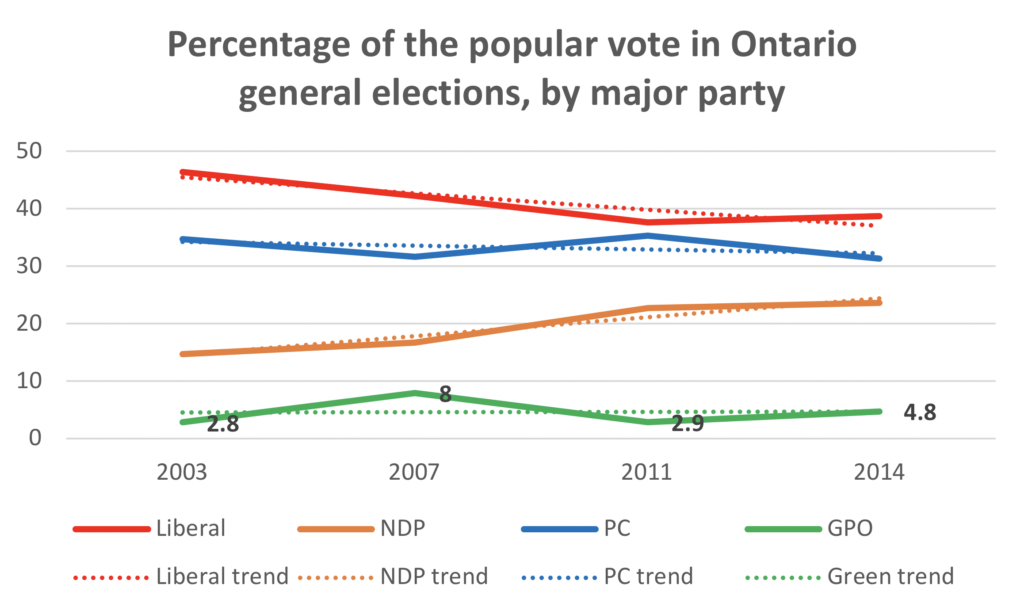

After winning less than 1 per cent of the popular vote in the five elections they contested in the 20th century, the Greens began to get more attention from voters in the 21st century. In the last four elections, the party has averaged 4.6 per cent of the popular vote—not enough to win a seat, but enough to influence some riding races.

While the Greens present themselves as neither left nor right, opinion polls have suggested that the second choice of most Green voters is either the NDP or the Liberals, not the PCs. In recent elections, the Green vote has risen in years where the PCs have faltered; there is a strong negative correlation between PC vote totals and Green vote totals.

This suggests that Green supporters have two priorities: first, voting for the party of their choice, and second, voting to block a PC government. If this is correct, a strong lead in the polls for PC leader Doug Ford means it’s possible many Green supporters could opt for their second choice in 2018.

Watch for the Trillium Party

Every election fields candidates from many small parties, but this time around, one small party in particular is worth watching: the Trillium Party.

Like Alberta’s now-defunct Wildrose Party (also named after a provincial flower), the Trillium Party aims to be a home for voters with a strong social and fiscal conservative bent, who favour grassroots party democracy more than the centralization of power under the leader.

The Trillium Party, which ran only two candidates and captured just a few hundred votes in 2014, received a shot in the arm in 2017 when Jack Maclaren, MPP for Carleton-Mississippi Mills, joined the party.

In the wake of Doug Ford’s decision to appoint 11 PC candidates rather than hold candidate nomination meetings in the affected ridings, other grassroots PCs have done the same. And Ford’s disqualification of outspoken social conservative Tanya Granic Allen as the PC candidate in the riding of Mississauga Centre after her supporters helped Ford win the PC leadership may make social conservatives stay home on election day—or vote for a conservative who is not a PC candidate.

No right-of-centre party in Ontario other than the PC party has won more than one per cent of the vote since 1990, when the Family Coalition Party and the Confederation of Regions Party took 4.6 per cent between them. Most PC MPPs elected in the 2014 election won by a wider margin than that, but the Trillium Party could play the spoiler in tight races.

Local candidates matter

The Liberals head into the 2018 election with at least a dozen sitting MPPs deciding not to run again.

Losing experienced campaigners who have won before is never good for any party, but local candidates impact campaigns in many ways. For example, PC leader Doug Ford has appointed 11 candidates of his own, in some cases against the wishes of local PC riding associations.

Among those appointees is Andrew Lawton, a controversial former media host, who will be the candidate in London West. Another Ford appointee, Mike Harris, Jr. (son of the former premier) is running in Kitchener-Conestoga after Ford ejected the sitting MPP from the PC caucus.

Ford’s appointments have done nothing to build loyalty among PC voters; they may end up having the opposite effect.

Getting out the vote is critically important

It doesn’t matter what polls say if a party’s supporters don’t actually go to the ballot box and vote. Parties get out the vote by having effective campaign machines, but they also get out the vote by putting forward policies that bring new voters into the fold.

In this election, for example, a large swath of minimum-wage workers can expect a $1-an-hour pay raise on January 1 if the Liberals or the NDP win. It may not bring more people to the polls than before, but it certainly could.

Small changes can make a big difference

In the 2014 election, the Liberals converted a minority government into a majority by increasing their share of the popular vote, compared to the previous election, by one percentage point, from 37.65 to 38.65. Coupled with a PC vote share that fell by 4.2 per cent, that one per cent spelled a nine-seat gain for the Liberals, boosting them to 58 seats.

Small changes mean less when the party in the lead has 40 per cent or more of the vote, but below that, they can be critically important.

Gaffes have changed many an election

Saying the wrong thing, putting forward a bad policy, or even having a bad picture taken can kill an otherwise adequate election campaign. An important point, though: mistakes hurt parties and candidates most when they serve to crystallize what people already thought about those parties and candidates. Other mistakes are just as easily forgiven.

The post-mortems will begin soon after the results start coming in on the night of June 7. At that time, one thing will become clear: getting more votes cures all ills. Regardless of party affiliation, all obstacles involving geography, vote efficiency, vote-splitting, candidates, and so on are overcome very simply: by winning more votes.

Unfortunately for all parties and candidates, this is seldom easy.

Randy Robinson is a political economist and commentator based in Toronto.