The school year has started with huge trepidation and heightened worry about the fate of our kid’s education and well-being, and growing fears about what the future holds as daily infection numbers climb.

Even if we manage to avoid a second wave of the coronavirus—a big if—there will be inevitable and lengthy disruptions in the event of illness among children, educators or staff. The supply of alternative child care is limited and costly. Families may or may not have other caregivers that can pitch in. This is certainly true for hundreds of thousands of single parent families working hard to pay the rent, feed and care for their kids within the narrow confines of their family bubbles.

So what will happen when the school closes for two weeks, or the rest of term? How will parents be able to work? How will mothers be able to work? Will mothers even have a choice?

Without support, the killer combination of trying to work, juggle child care and support children’s schooling indefinitely may push back women’s rights and opportunities by decades. Are we going to stand by and watch this happen?

Disproportionate job loss, lagging recovery for most marginalized

The economic security of women in Canada has been disproportionately impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, threatening equality gains. Women are returning to work or picking up additional hours, but months after the onset of the crisis their employment lags behind that of men, and their economic security remains fragile.

Economic losses have fallen most dramatically on women living on low incomes who experience intersecting inequalities based on race, class, education, sexuality, disability, and migration and immigration status. Many have lost employment or had their hours cut back significantly and are now sitting on the sidelines of the recovery.

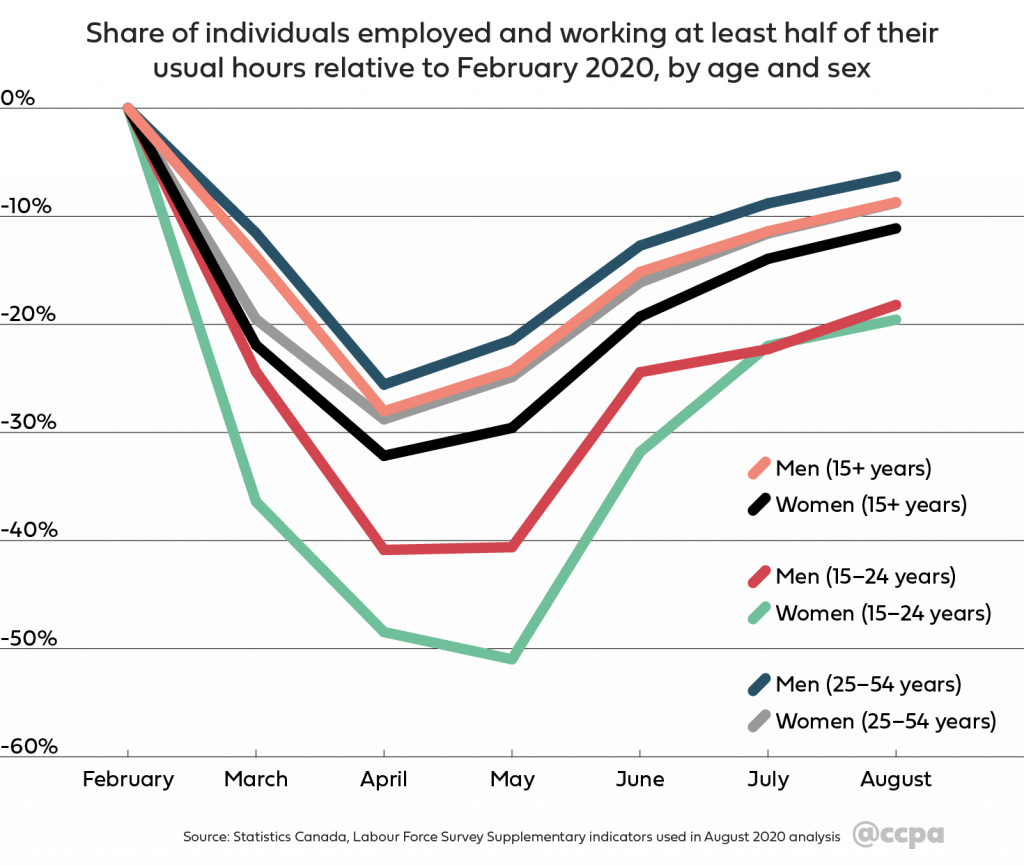

The August jobs report from Statistics Canada shows that, since April, women have recouped almost two-thirds of February-April employment losses (63.4%), and less than one-half of full-time job losses (46.2%). Core-aged women (25–54) saw larger gains than youth (15–24) and older women (55+). For all age groups, the recovery among men is more advanced.

Women’s job growth has been mostly in part-time work. A summer boost in part-time work in hard-hit industries such as retail and food services spurred employment among low-wage workers, but their rate of recovery continues to be slower than that of higher paid employees, lagging by 12 percentage points (87% vs. 99%), notably among women (at 86%).

Not everyone is finding their way back to the labour market. A large group of women who left the labour force through the first months of the pandemic have yet to return. Among core-aged women (aged 25-54 years), the number of women outside of the labour market increased by 425,000 (or 34.1%) between February and April. By August, the size of this group was smaller, but still in excess of 100,000 workers—roughly three-quarters (76.0%) of February’s levels.

Single parents have nowhere to turn

Gains in employment have been especially weak among mothers with children under 12, pointing to the impact of school closures, uncertain access to childcare and unequal division of labour in the home.

By August, fathers had effectively recouped all of their losses, while 11.7% of the mothers (over 236,000) who were working in February were still without work or working less than 50% of their regular hours.

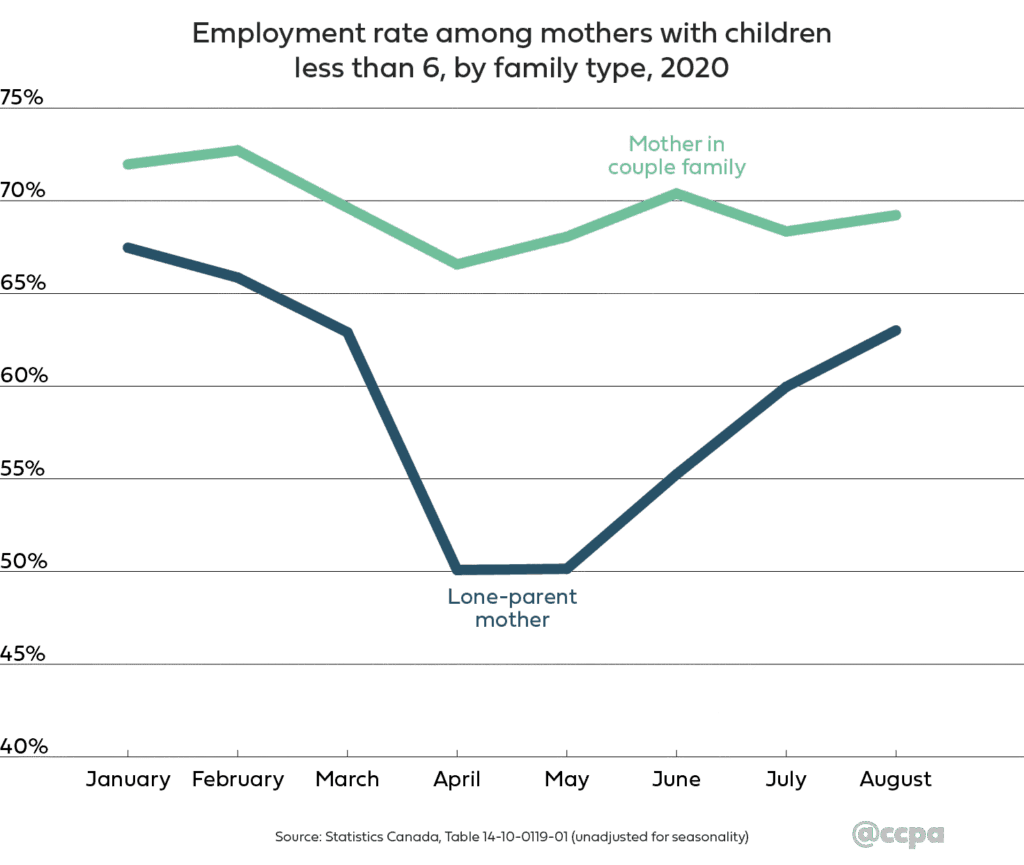

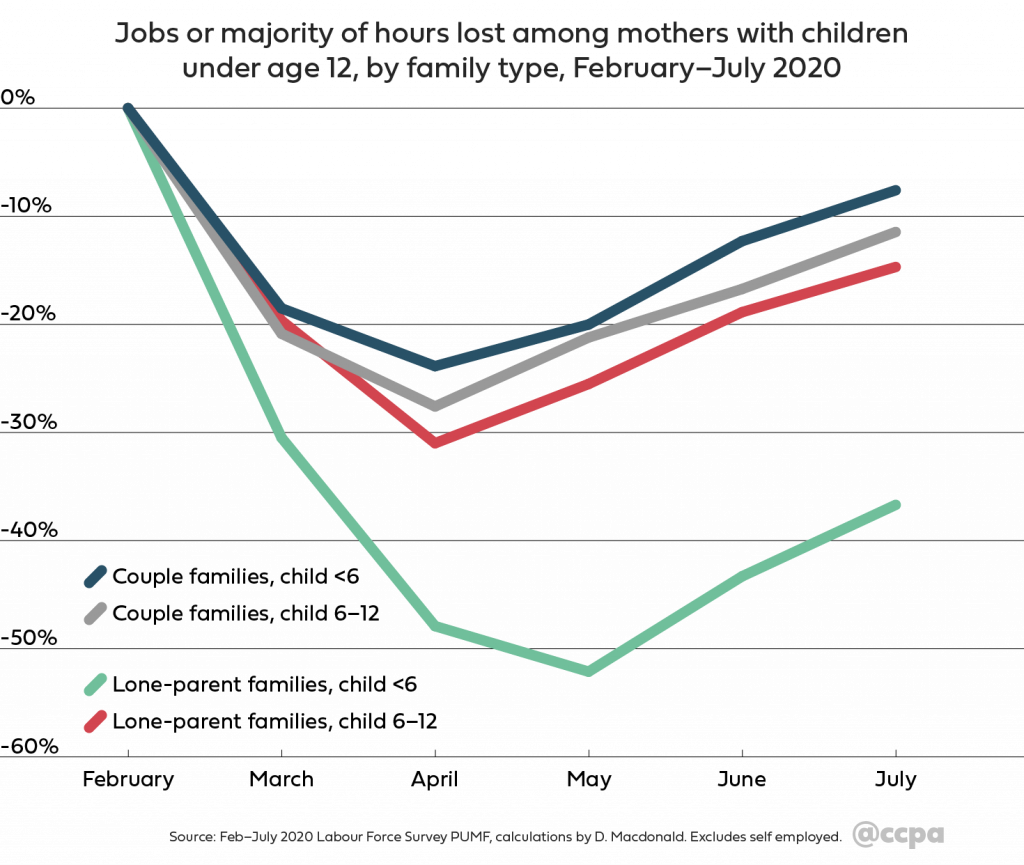

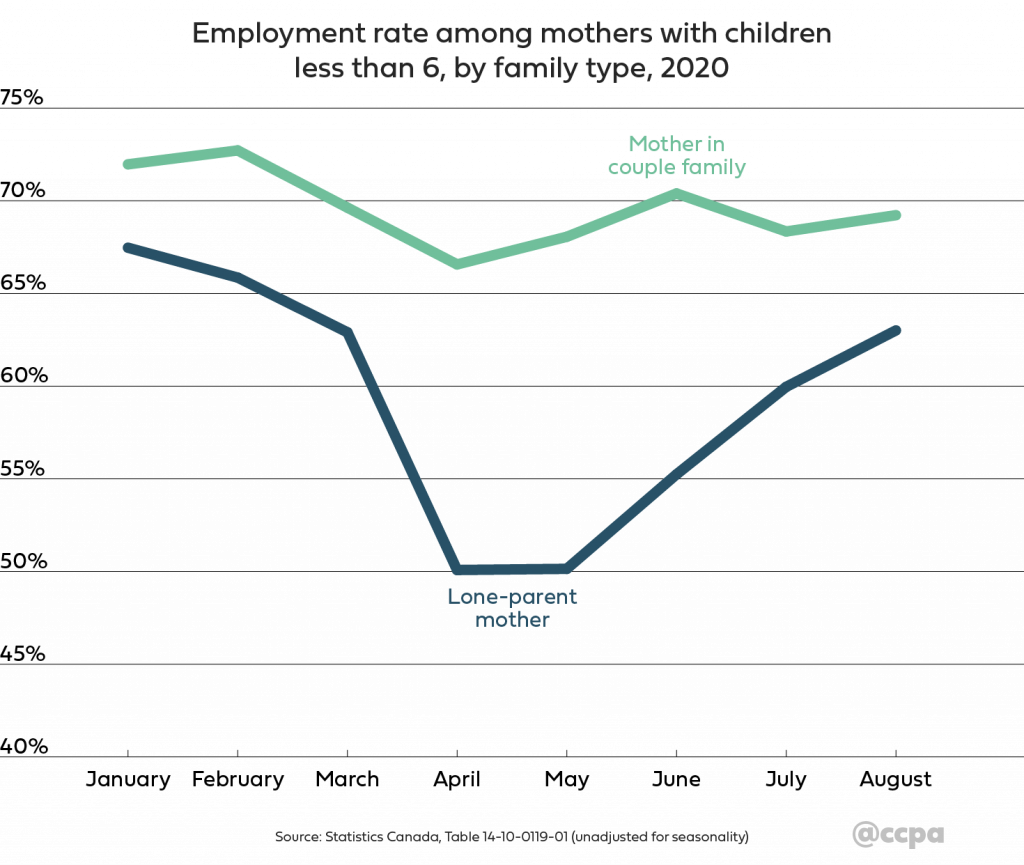

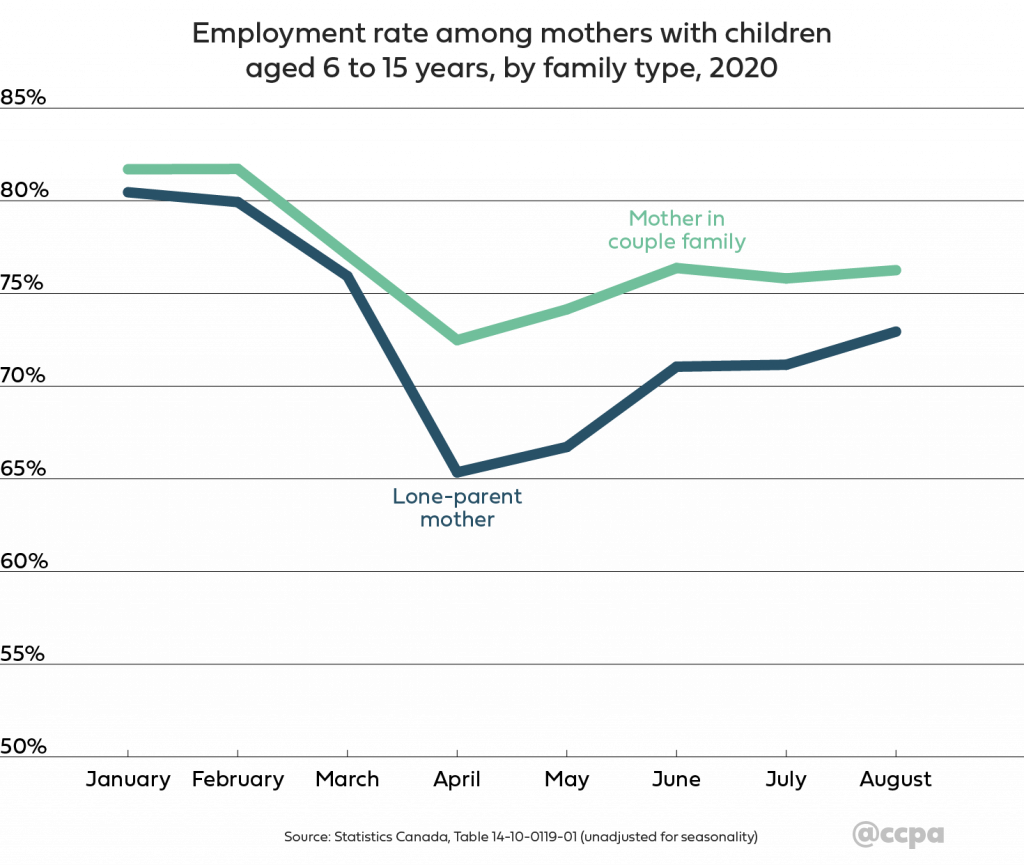

On this score, lone parents have experienced greater loss of employment and are recovering much more slowly than parents in couple families. Concentrated in “flexible” occupations such as sales and service, over one-third (37.5%) of single mothers with kids under 12 lost their jobs or a majority of their working hours when the economy shut down in the spring compared to one-quarter (25.5%) of mothers in couple families.

By August, single moms had only recouped a fraction of their employment losses and many were still working less than half time. One in three (29.2% or 75,000) were unemployed or working reduced hours as a result of the pandemic, including 42.2% of mothers with kids under six.

Rates of employment among mothers with children (aged 0-12) living in couple families are also still much lower than in February, especially among those with school-aged kids (6-12 years). This coincides with an increase in the number of mothers (among both lone-parents and mothers in couple families) who are employed but absent from work on leave.

The lack of coherent plans to safely reopen child care and schools creates huge barriers for mothers looking to re-enter the workforce. Social norms and traditional caregiving roles, which have contributed to gender gaps in pay, are now pushing mothers, rather than fathers, out of the labour market and into full-time caregiving and homeschooling.

This suggests tremendous economic hardship lies ahead. Prior to the pandemic, women earned 42% of household income and were, on average, responsible for almost half of household spending. The precipitous collapse in employment will inevitably lead to higher levels of low income and poverty, not just in the coming months, but, for years to come.

For single mothers, the economic lockdown wiped out two decades of economic progress at a stroke. And lack of support now threatens their recovery. Poverty rates among single parent families were already considerably higher than in couple families going into the pandemic. It has now magnified these stresses exponentially. And the numbers of those living in poverty are set to explode.

No child care, no recovery for women

The pandemic has demonstrated how economically and socially precarious many Canadians—and the services they depend on—are after 30 years of austerity and privatization. The pandemic has also exposed the systematic undervaluing of paid and unpaid care work.

Figures from Ontario’s Ministry of Education reveal that only half—half!—of the province’s child care centres had opened by the beginning of September. The challenges are acute in other provinces as well. Federal funding for child care announced under the Safe Reopening Agreement has helped with the purchase of PPE and some operating costs, but it’s too little, too late for many centres and homes struggling to lure back qualified ECE staff with low wages while backfilling significant financial losses incurred over the last six months.

Governments are standing by while critical infrastructure collapses, clearly with the expectation that families—and mothers in particular—will step in to shoulder this massive increase in unpaid labour. If 50% of our roads and bridges were at risk of collapsing, as senior economist Armine Yalnizyan has argued, we’d have a national plan. We’d have a strategy in place to ensure that the recovery doesn’t stall in the event of a resurgence of the virus and predictable rise in on-demand employment.

Add in the uncertainty associated with deeply flawed school and child care reopening plans, mothers now on the edge will walk away from their jobs. Fifty years on from the release of the Royal Commission on the Status of Women, and it’s come to this.

**

There is a lot riding on the federal government’s Speech from the Throne, set for release on September 23rd. To move forward, we must centre the needs of the most vulnerable in our efforts. We can’t afford to wait: Immediate action is needed to address the precarious position of mothers – and single mothers in particular – who are at risk of being sidelined from the recovery and a secure future altogether.

Katherine Scott is a Senior Economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow her on Twitter @ScottKatherineJ.