The COVID-19 pandemic presented Canada and the world with enormous challenges that may reshape our reality for decades to come.

In Canada, the pandemic revealed massive holes in our social safety net, gross inequality between the rich and poor and shameful structural socio-economic and health disparities determined by gender, race, age and more.

As we continue to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, we grapple with how to improve our country and world: in public health, the economy, how we care for others and how we ensure a sustainable climate.

There is no one way to tell the story of COVID-19. Instead, we asked CCPA researchers to present charts, based on their area of expertise, that each offer a different way to understand the time we currently live in.

Women bore the economic brunt of COVID-19

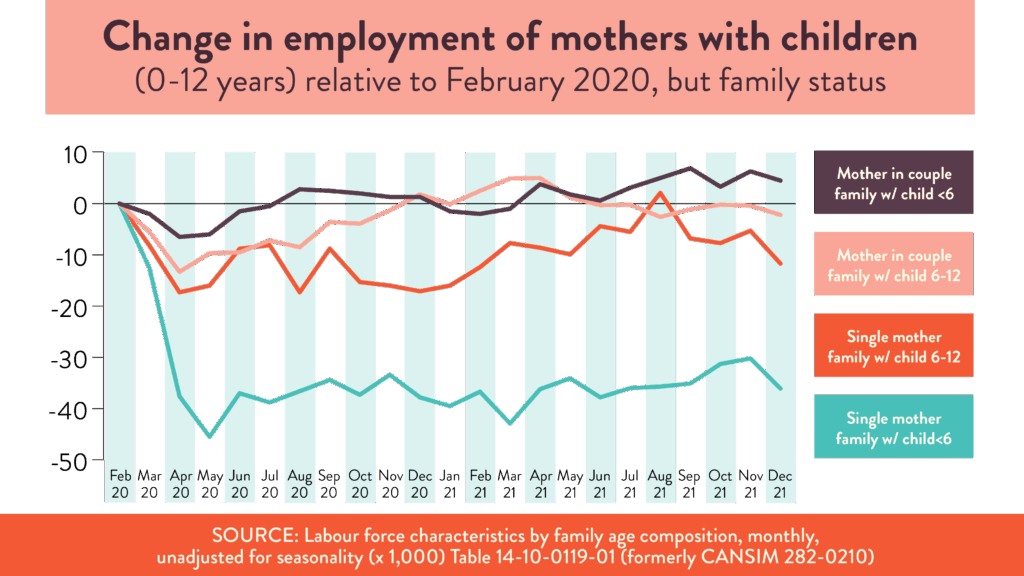

The pandemic saw the labour market decline and recover throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, but the road back to pre-COVID employment has not been equal for lone-parent families with young children. Levels of employment among those with children under the age of six have shown little improvement since the historic losses experienced during spring 2020. As of December 2021, employment was 36% below February 2020 levels and 12% below for single moms with children aged six to 12.

This huge gap speaks to the failure of Canada’s care infrastructure to support the most vulnerable during the past two years. Essential community supports, already fragile before the pandemic hit, came under acute stress due to rising demand, chronic underfunding and declining revenue. The very low wages and lack of benefits, such as paid sick days, that characterize female-majority caring services remain a huge barrier. Child care workers are exiting the profession in droves.

The new federal child care program is a huge win for parents and communities. This could represent a real turning point. But it isn’t clear at this juncture whether the agreements that have been struck with provincial and territorial governments will deliver on the promise of a universal system.

—Katherine Scott, senior researcher

Indigenous workers were more exposed to COVID-19

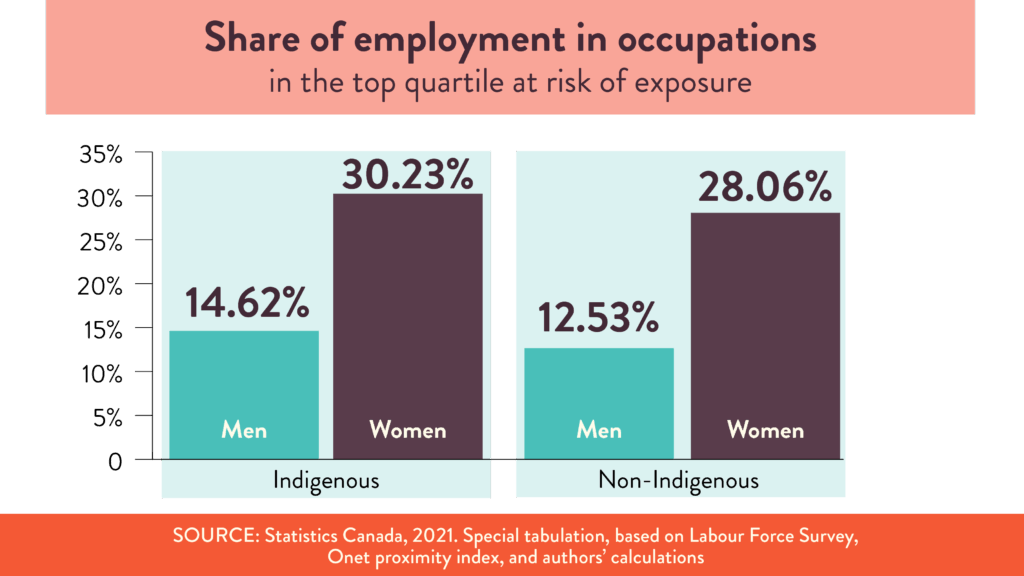

The economic and health impacts of COVID-19 were not randomly distributed and did not affect everyone equally. They were more severe for marginalized people. Throughout the pandemic, workers in predominantly lower-wage occupations faced a higher risk of contracting COVID-19 at work. Indigenous women had the highest share of employment in occupations ranked in the top quartile for physical proximity, at 30.2%. Next, were non-Indigenous women, at 28%, followed by Indigenous men at 14.6%, and then non-Indigenous men at 12.5%. These findings should make us question whether we were ever “all in this together.”

—Sheila Block, senior economist, CCPA-Ontario

Long-term care operators profit amid mass dying

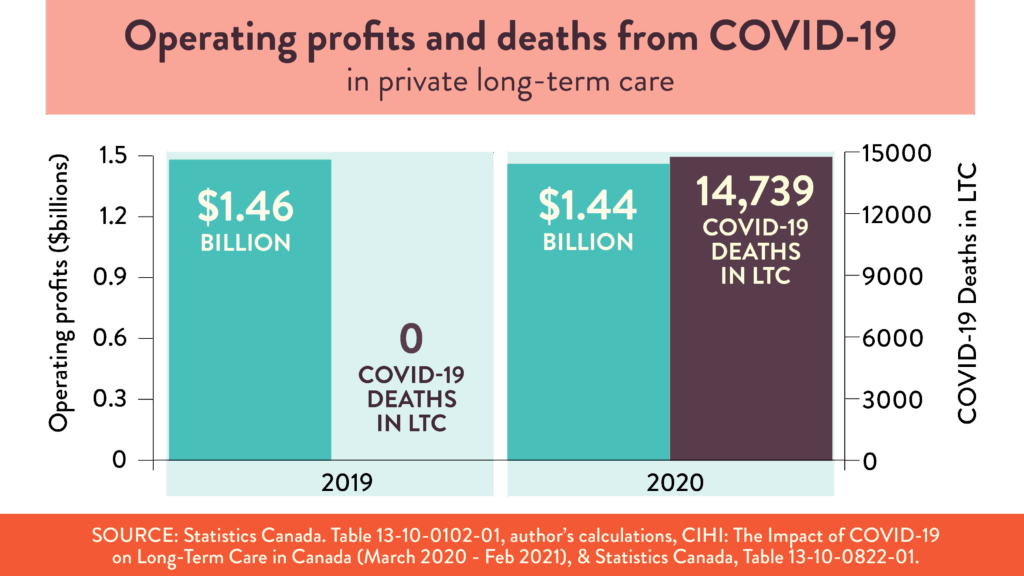

Two years into the COVID-19 pandemic, Canada’s long-term care homes remain a tragic symbol of neglect. The majority of COVID-19 infection rates and deaths were concentrated in the for-profit sector; a sector owned and operated by major chains that continued to reap $1.4 billion in profits, despite the mounting death rate in their homes.

Large private chains, now expanding across Canada, generated sizable profits for their

shareholders through short staffing, lower wages, benefits, and pensions. Across Canada, for-profit facilities have 34% fewer staff and spend less on direct care than homes under public ownership.

Governments must work collaboratively to bring private facilities and services fully into the public system, under a framework of robust national standards of care. This will require substantial investment to expand quality institutional and home care in the public and non-profit sectors. In a country that spends 30% less than the average OECD country on long-term care, this investment is long overdue.

—Katherine Scott, senior researcher

Vaccine inequity leaves everyone worse off

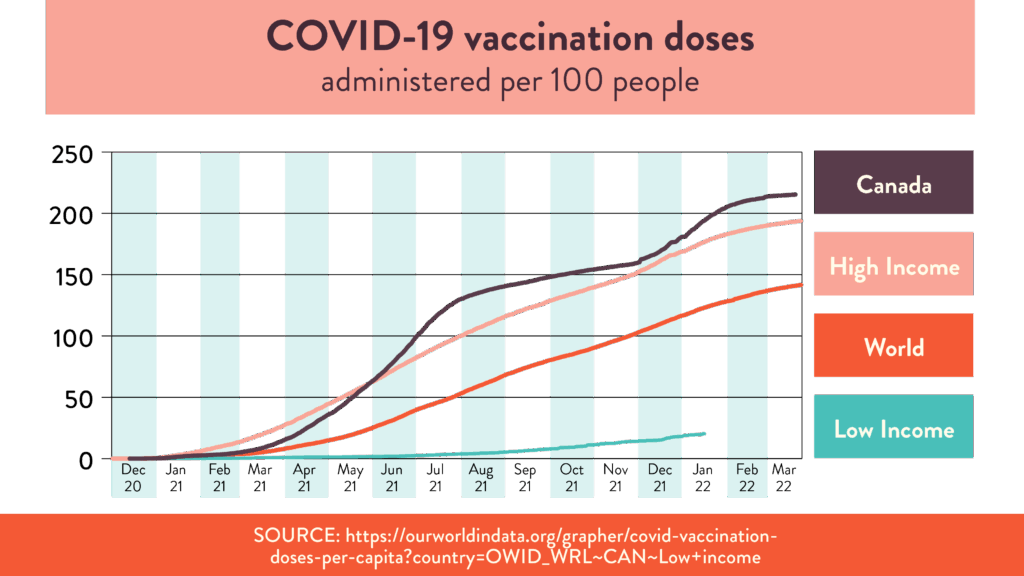

“No one is safe until everyone is safe'' became a core motto early into the COVID-19 pandemic. If only anyone believed it. At first, when containment and treatment were the priority, wealthier countries panic-hoarded or put export bans on face masks, ventilators, and other personal protective equipment, leaving low-income countries high and dry. Then, as vaccine candidates came online in late 2020, those same wealthy countries, including Canada, bought the lion’s share of doses and continued to do so into 2022.

The predictable and preventable outcome was a huge vaccination gap between high- and low-income countries, most notably in Africa. Patent-holding vaccine makers like Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna made a killing and successfully lobbied against efforts to remove trade barriers to producing cheaper generic versions of their products in low-income countries. Vaccine supply is finally catching up with global demand, but logistical constraints and vaccine hesitancy in Africa, much of it absorbed from the West, threaten a Canadian-style vaccination success in large parts of the world.

—Stuart Trew, director of the Trade and Investment Research Project

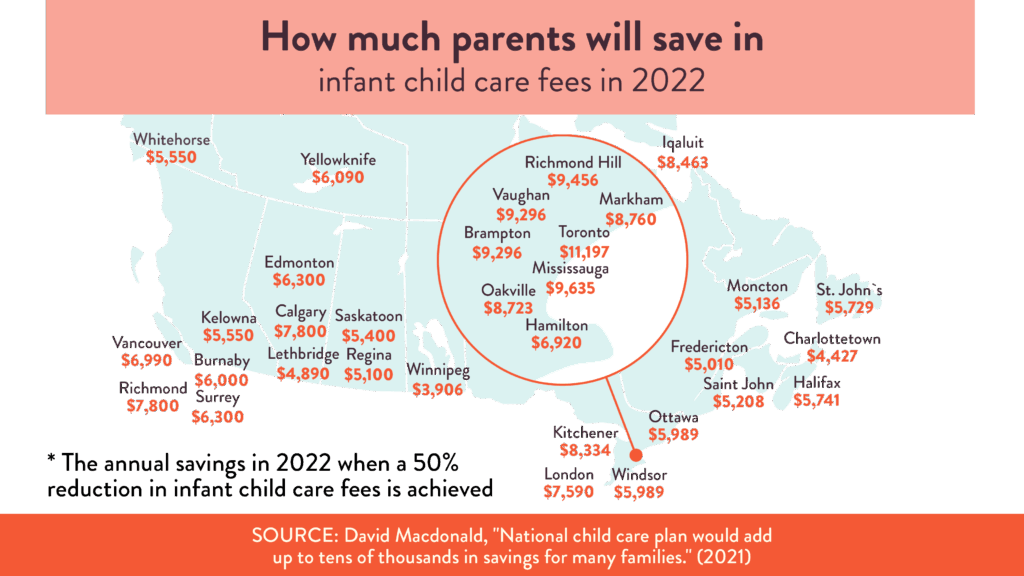

Affordable child care is coming, will we hit the ambitious targets?

2021 was a historic year for child care in Canada as the federal government, after decades of calls from advocates and a pandemic that further exposed the economic disadvantage for mothers, passed a comprehensive national child care plan. 2022 is perhaps even more historic as all the provinces have now signed on, including the last to the party, Ontario. Now it's not a question of whether we'll have a national plan, but how we'll implement it. There could be substantial savings for parents with young children, although different provinces are taking different approaches. Some will likely hit their 50% reductions by the end of the year but others likely won't. Fair pay for Early Childhood Educators and the creation of enough new spaces are still moving targets we’ll need to watch closely.

—David Macdonald, senior economist

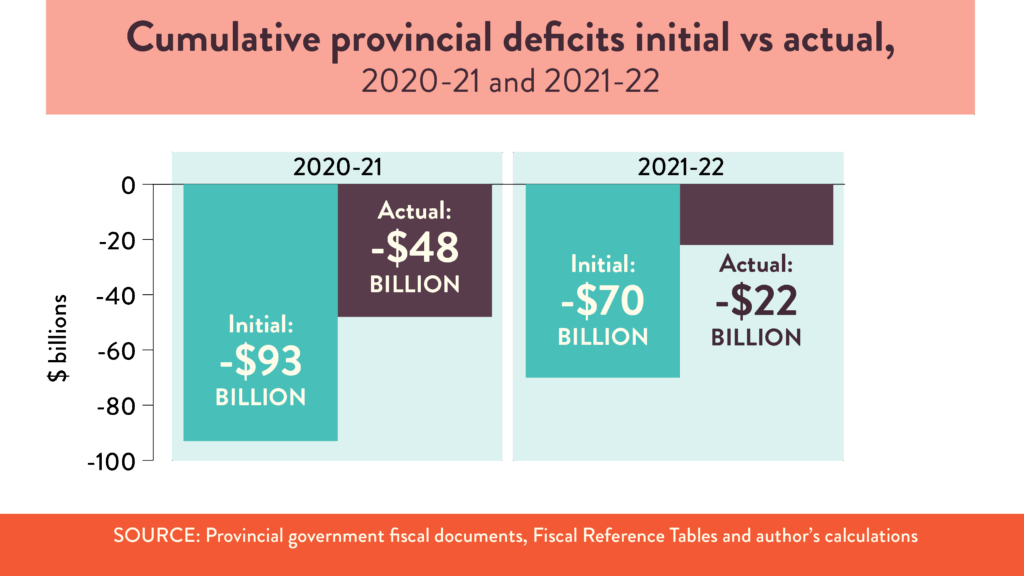

Provincial finances are strong in 2022, let’s fix what the pandemic broke

COVID-19 caused such economic uncertainty early on that it was truly difficult to understand what impact it would have on the economy and on government books. Thankfully, the initial projections of massive deficits in the first two years of the pandemic were wildly wrong. In the first year of COVID-19, 2020-21, deficits were half of what was initially projected. In the second year of the pandemic, deficits were two-thirds lower than initially projected. As provincial economies roared back in 2021, revenue projections turned out to be far too pessimistic. By April 2022, six of 10 provinces will be in a surplus position and the ones that aren't will be very close to a balanced budget. This puts provincial governments in a much better position to tackle the challenges of COVID-19, such as making the health care system more resilient to future waves and building a long-term care system that treats seniors with the dignity they deserve.

—David Macdonald, senior economist

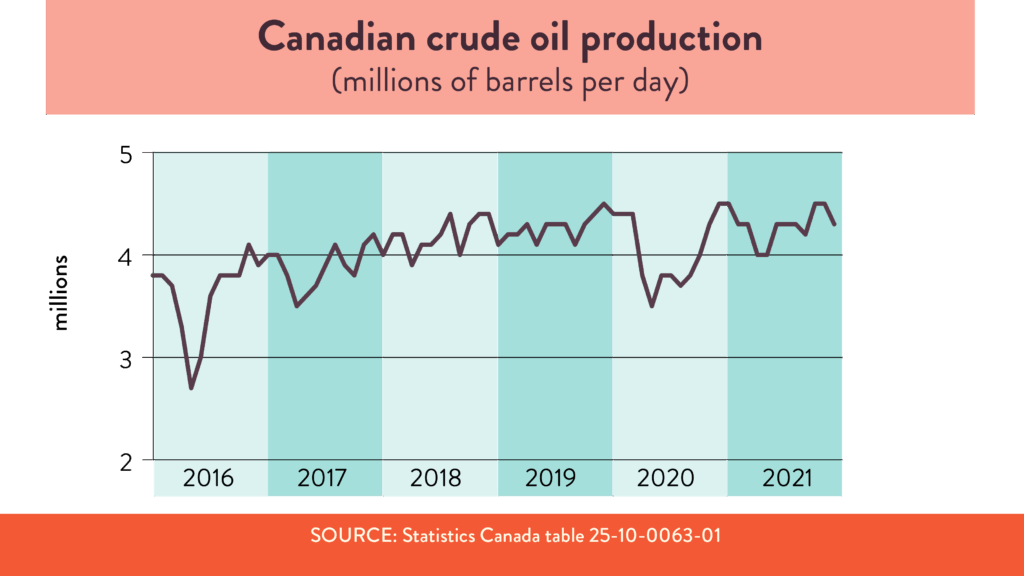

COVID offered a chance to speed up climate action. Instead we produced more oil

Global demand for oil fell precipitously when COVID-19 hit and oil producers responded by cutting production. There was a brief window when it looked like oil had peaked and the world would rebound from the pandemic with a decisive, climate-conscious shift into a renewable energy economy. Not so much. Two years after the crash, oil prices are smashing records and the Canadian oil industry is producing as much crude as ever before, with no sign of slowing down.

How did Canada miss this glaring opportunity to curtail oil production in the midst of a climate emergency? By focusing on the wrong kind of policies. Federal and provincial governments have emphasized demand-side policies, like carbon pricing and methane emissions regulations, but they’ve shied away from supply-side policies that would directly constrain oil production. It may not be popular, but getting to zero requires a proactive plan to phase out fossil fuels.

—Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood, senior researcher

Charts by Katie Sheedy