Over the past week, we've been evaluating Canada’s economic recovery. Today is the last post in this blog series.

There is no dispute that Canada has had a ‘recovery’ – both Canada’s economy and unemployment have improved since the end of the low point of the recession – but the question is the quality of that recovery.

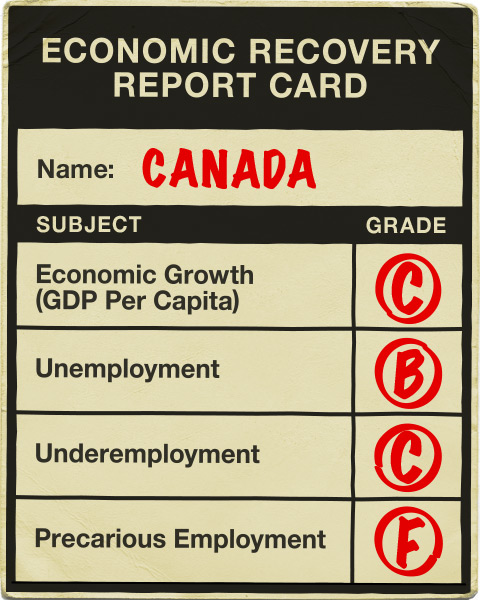

On Monday, we looked at GDP growth. We found that when adjusted for population growth, Canada’s recovery in Real GDP per capita has been pretty mediocre, ranking 4th in the G-7 and 16th of 34 countries in the OECD. Canada’s OECD rank translates to a C according to our grading methodology.

On Tuesday, we looked at the employment market in Canada and found serious flaws in the way the government was communicating the health of the labour market. Looking at unemployment rates, we found that Canada has only partially recovered since the recession. The recovery in Canadian unemployment rates places us 4th in the G-7 and 10th in the OECD. This equates to a B grade based on the OECD ranking.

On Wednesday and Thursday, we looked at how the quality of jobs has changed over the recessionary and recovery periods. Underemployment – people working part-time but wanting to work full-time – was examined Wednesday, where Canada received a C. Precarious employment – short-term and temporary employment with no security – was examined on Thursday. Canada’s poor performance in this measure earned an F, the worst grade received in this blog series.

The grades assigned to Canada’s recovery are as follows:

Canada’s recovery has been mediocre and unexceptional by international standards. Many countries in the OECD have experienced stronger recovery’s than Canada has. This is likely why the government uses the G-7 comparison so frequently – it creates an impression of economic success – but the truth is more nuanced.Examining more representative economic measures with a broader international comparison group, Canada is a mediocre ‘student,’ receiving C’s and B’s in most areas, with an F in the precariousness of work. In real terms, this means that the strength of our recovery (GDP and unemployment) has been at or below average and the quality of employment (underemployment and precariousness) has suffered during the recovery.

Clearly, Canada’s economic growth doesn’t live up to the hype.

Counter to the federal government’s claims of good economic stewardship, Canadians are suffering through unemployment, underemployment, or precarious work. Currently in Canada, there are:

<li>1,315,800 people unemployed,<a title="" href="#_edn1">[i]</a></li>

<li>908,200 people who have jobs but are underemployed (involuntary part-time)<a title="" href="#_edn2">[ii]</a>,</li>

<li>2,434,300 people whose employment is precarious and non-permanent,<a title="" href="#_edn3">[iii]</a> some of whom may also fall in the underemployed category.</li>

But this doesn’t need to be the situation; there are alternatives. The federal government can create more jobs programs and active labour market programs, as suggested in CCPA’s Alternative Federal Budget. For instance, now would be a great time for a larger investment in infrastructure to create jobs and help boost Canada’s economic recovery. Likewise, Canada has a major housing crunch and investments in constructing new affordable housing would help create jobs and social good.

And lastly, all governments should end the austerity agenda—which is only further stifling our precarious economic recovery.

Maybe then Canada will start getting straight “A”s.

To learn more about the methodology behind this blog series, click here.

Kayle Hatt is the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ 2013 Andrew Jackson Progressive Economics Intern.