There is something great about summer in Canada; it’s hot but also full of promise with places to visit, camping, travelling, cottaging, trips to the beach and various summer events and festivals.

For many of Canada’s students, however, summer has not been so great. New data from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey released Friday shows that students are struggling to find summer jobs for the sixth year in a row.

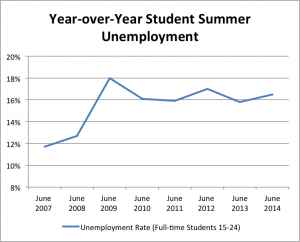

The unemployment rate for full-time students between 15-24 was 16.5% in June, down from 18.3% in May. Higher student unemployment at the beginning of summer is a pattern and it almost always falls between May and June as students find positions or give-up looking. This is about a third higher than pre-recession levels at the same time of the summer.

Looking at the unemployment rate at this point in previous years (there is no seasonally adjusted data available), you can see how students have fared in the post-recession period. Student summer unemployment has barely recovered from the economic shocks of 2008-09 and has been stagnant since the summer of 2010.

Looking at the unemployment rate at this point in previous years (there is no seasonally adjusted data available), you can see how students have fared in the post-recession period. Student summer unemployment has barely recovered from the economic shocks of 2008-09 and has been stagnant since the summer of 2010.

Beyond the unemployment rate increase, student participation in the labour market has also declined (perhaps as some students have come to feel that summer classes and the accompanying student loans are a better bet than finding a summer job). The unemployment rate measures the number of people who don’t have a job but are looking for one, since students are participating less in the labour market, the employment rate (the number of people employed) is helpful in seeing the extent of the post-recession change.

The summer employment rate for full time students in June 2008 was 55.3%, this June it was 49.7%. In terms of employment rates for students in the summer, there has been no recovery since the worst of the recession.

Squeezed on both sides

You might be forgiven for asking “why does student unemployment matter, when Canada has lingering problems with unemployment for non-students?”

Canada does have a significant youth unemployment problem for non-students, which needs to be addressed. But that doesn’t mean that summer employment for students isn’t also important.

As CCPA has pointed out in the past, students are under pressure from steadily increasing tuition rates and other expenses. And while university has gotten significantly more expensive, with costs rising far faster than inflation, wages haven’t kept pace. In Ontario, for example, it takes 2.7 times longer than it did in 1975 to pay for the average cost of a year at university at a minimum wage job. (See CCPA’s interactive application for province and program specific information.)

The result is that students are being squeezed on both sides, trying to cope with the higher cost of university and growing debt on one side while having a harder time finding jobs to pay for it and, if they’re lucky enough to find a job, having to work longer to cover costs. When baby boomers say “in my day I worked in the summer to pay for school instead of getting loans” that’s a fairy tale; it may have been true at once upon a time but these days it that has no more social relevance than Sleeping Beauty does (what exactly is a spindle anyway?).

Furthermore, temporary summer jobs help students gain important skills and marketable experience that can improve long term prospects. A recent study found that high school students who worked a part-time job in the school year or a summer job between years had better outcomes in their mid-twenties. Other research shows that university graduates with work experience have an easier time finding post-university employment.

Alternatives?

In searching for solutions to this problem, it might be helpful to look at how government cuts have contributed.

When the Conservatives came into power in 2006, they cut the old Summer Career Placement Program that provided summer work experience up to 55,000 students and replaced it with the Canada Summer Jobs Program, but only for half as many students. Despite the worsened labour market conditions, the Canadian Summer Jobs Program still only provided 36,077 subsidized placements in 2012-13 and funding for the government’s Youth Employment Strategy umbrella strategy has been cut from $275 million in 2010-11 to $211 million in 2012-13[i].

Past audits and evaluations of the SCPP and SJP have found that most employers who had taken students as part of this program had not planned to hire or would not have been able to do so without the wage subsidy (in part because the programs target funding partially to cash-strapped non-profits).

If we want to decrease the slack in the student labour market then reversing these cuts and expanding the ambition of our youth employment programs would be an important first step.

There were 106,000 full-time post-secondary students (between 20-24) who wanted to work last month but couldn’t find a job. We should do something to help them.

Kayle Hatt is a Research Associate with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ National Office and was the CCPA’s 2013 Andrew Jackson Progressive Economics Intern. Follow Kayle on Twitter at @KayleHatt.

[i] HRSDC, Departmental Performance Report, 2012-13