Photo by Kevin Jarrett, Flickr Creative Commons

Photo by Kevin Jarrett, Flickr Creative Commons

The dangers of corporate monopolies in our communications have been recently revealed through exposés of social media corporations like Google and Facebook. Almost unnoticed, though, has been a similar analysis of the way in which these same corporate monopolies have been colonizing and privatizing public education under the guise of “21st Century learning.”

Colonization is a process where a significant force moves into an area and dominates. It takes over not only the production and resources, but imposes—often by stealth and power—the processes, approaches, and even the values of the social and cultural environment.

And dominate is what the monopolistic technology platforms are on track to do in public education.

The top five global capital corporations are platforms in the technology field—Apple, Google, Microsoft, Amazon and Facebook—from which a variety of services and uses can be hosted. While the big five compete against one another, adding services to keep users on their platform for everything they do online, the sheer size of these entities ensures there is no significant competition from outside this select group. If a new, potentially competitive service seems to be gaining users, it is quickly purchased and integrated into an existing platform. Alternatively, the big five can use their massive resources to develop a comparable app and push the potential competitor aside.

The author of Platform Capitalism, Nick Snricek, points out that this form of monopoly “introduces new tendencies within capitalism that pose significant challenges to a post-capitalist future.” Building public, cooperative platforms becomes an impossible dream.

In the pursuit of new growth opportunities, it’s no surprise that the tech platforms have moved into public education, which represents a big chunk of potential revenue. Just as importantly, education is where one can find most of the future consumers and (potentially ongoing) users of platform services.

The most successful corporation here has been Google. A recent report indicates that Google’s G-Suite for Education is being used by half the teachers and students in the U.S. It includes a range of free software tools that can be used by students and teachers—word processing, presentations, spread sheets and the like. G-Suite incorporates “Classroom,” an integrated learning management system that keeps track of grades, attendance and more. And, of course, YouTube is linked for student use.

New elements are added frequently. “Google Sites” is promoted for student e-portfolios, because “every student should publish for the world.” Google acquired Workbench, integrated with Google Classroom, to give “lessons connected to a variety of ‘maker’ activities focused on STEM.” It is part of Google’s plan to “help schools and educators address their universal needs around education content.”

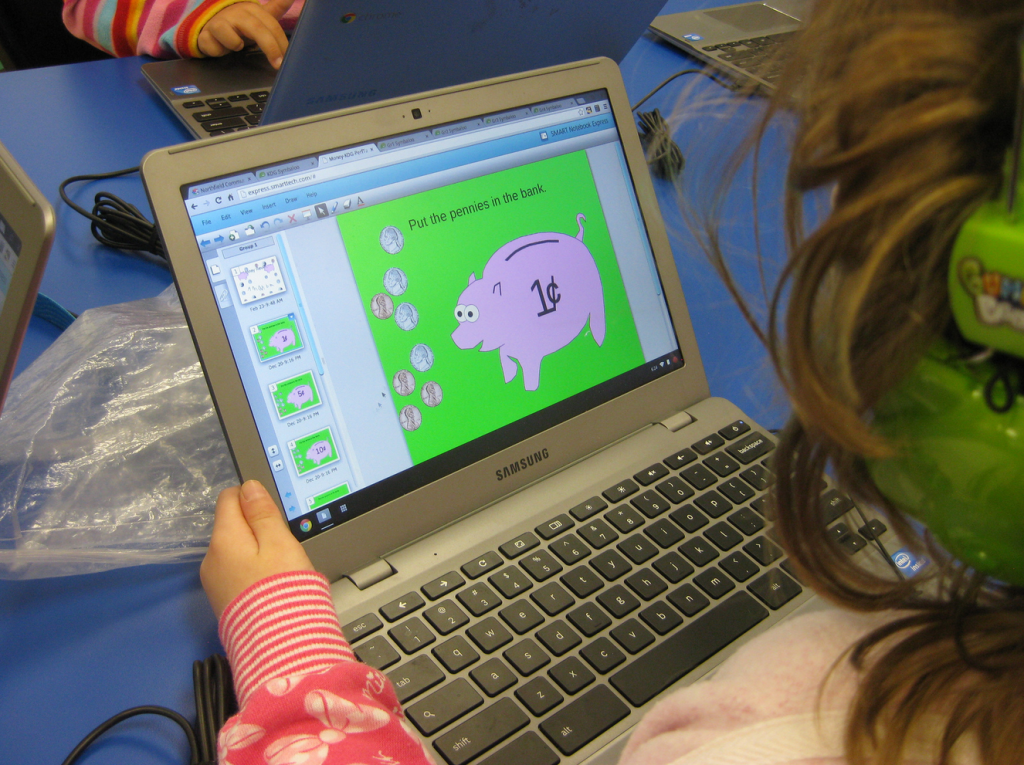

So, rather than democratic public institutions, Google shapes what is on offer. Google’s position as edu-colonizer is strengthened by the hardware increasingly used in schools—the Google Chromebook. It is less expensive than other computers because much of what it needs to operate—operating software, applications and memory—is supplied by Google in the cloud rather than being included with the computer. According to market reports, Chromebooks make up the majority of all computers sold to schools in the U.S. and they are also marketed globally.

However, one must have a Gmail account to use these Google tools—so the kid whose parent wants to protect the privacy of their child and refuses a Gmail account is left out, while the rest of the class works away on their Chromebook and its accompanying slate of Google tools.

Google has even taken up teaching “internet safety,” with a program aimed at reaching five million students. Its core is a game for students in Grades 3 to 6 to teach them to avoid “schemers, hackers and other bad actors.” However, as critics point out, it doesn’t talk about privacy concerns when users’ personal information and actions are tracked online—activities in which Google itself is directly implicated.

A Swedish study of Google’s strategy concluded that: “By making an implicit demarcation between two concepts—(your) ‘data’ and (collected) ‘information’—Google can disguise the presence of a business model for online marketing and, at the same time, simulate the practices and ethics of a free public service institution.”

In her article, "Ed-tech in a Time of Trump," Audrey Watters points out that: “The risk isn’t only hacking. It’s amassing data in the first place. It’s profiling. It’s tracking. It’s surveilling.” (For more on this topic, see A Hack Education Project.)

Google isn’t alone in the business of colonizing education and mining student data—it’s just the most successful at it… so far. One competitor is Microsoft 365 Education, which will “unlock limitless learning” with a promise of “empowering every student on the planet to achieve more.”

Microsoft 365 is the cloud-based provision of software and cloud storage for your work that is the new business model for Microsoft. They don’t sell you software, you rent it—and keep paying for it. And your work isn’t saved on your own computer, so you have to keep up your subscription. Like Google, Microsoft is hoping that students will keep using their tools when they finish being students.

Here, Microsoft imitates much of what Google provides, but by charging for the service rather than trading it for data. It offers apps, educator training and STEM lessons “to enrich science, technology, engineering and math classes,” and “budget friendly” Windows 10 devices with licences for Microsoft 365 Education.

While Microsoft and Google are prominent in the pursuit of the classroom, neither are pioneers of the sector. Apple was the first into education way back in the '80s, with the Apple IIe and the “Apple classroom of Tomorrow." More recently, Apple has promoted the iPad’s ease of use, despite its cost, to convince schools to buy class sets; it also, in collaboration with Pearson, engaged in an ill-fated project in Los Angeles schools.

And the frenzy continues as venture capitalists hope to find the magic app that will make a fortune, and as hundreds of millions of dollars are spent each year on developing new products that will either be bought or copied by one of the major corporations.

Meanwhile, shockingly little attention is paid by education authorities or researchers to the way in which technology monopolies have the potential to not just shape but distort public education.

Larry Kuehn is Director of Research and Technology at the British Columbia Teachers’ Federation (BCTF). An earlier version of this blog was published at IPE/BC.