One of the apparent silver linings of the COVID-19 lockdown has been a significant drop in air pollution in cities around the world.

Although the effect has been most pronounced in notoriously polluted places like New Delhi, Beijing and Los Angeles, we’ve seen improvements in Canada as well. As I wrote last month, pollution levels in major Canadian cities dropped as much as 15% in March 2020 compared to March 2019.

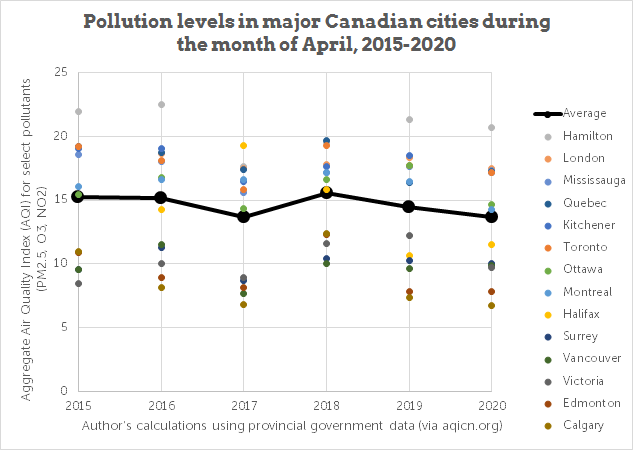

Now that we’ve reached the end of our first full month in lockdown, we can see a similar effect for the month of April (see chart). Across 14 of Canada’s biggest cities, pollution levels declined an average of 5% in April 2020 compared to the same period last year. When compared to the average April between 2015 and 2019, the drop in April 2020 was about 8% across the country.

Calgary experienced the biggest decline in air pollution with a drop of 26% in 2020 compared to the preceding five-year period. Halifax, Edmonton and Montreal also saw double-digit improvements. Most other cities saw smaller but still significant declines in pollution.

This improvement in Canadian air quality is good news for our health and for our efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but it should also give us pause. Major sectors of the economy are in hibernation, consumer spending is down dramatically, millions of people have lost their jobs and millions more aren’t leaving their homes to drive or fly around. And yet pollution levels have only declined by 5-10% in most parts of Canada?

On the one hand, this modest change should come as little surprise. Firstly, most of our pollution comes from sectors of the economy, such as oil and gas extraction, heavy industry, electricity generation and commercial transportation, that have not been shut down to the same extent as the service and retail sectors. Emissions from sectors like oil and gas or manufacturing have very little do with our individual behaviours, at least in the short term.

Second, we’re continuing to produce a lot of the same pollution during lockdown, just in different forms. For example, instead of heating our office buildings during the day, we’re now heating our homes more often using the same sources of natural gas or electricity. Our individual choices about energy use are largely determined by the energy system we’re a part of.

On the other hand, we have often been told that if only we drove less, flew less and consumed less—if only we reduced our personal carbon footprint—we could do our part to solve climate change.

There is great value in making ecological choices, but it was never going to be the whole solution. What the COVID-19 lockdown is showing us is that, when it comes to reducing air pollution and, by extension, fighting climate change, our individual actions are not even remotely enough.

To cut emissions dramatically—to decarbonize the economy as we have promised to do in the next 30 years—will require large-scale structural changes to our energy system and our broader economy.

It’s especially important to be having that conversation now, when the future is so uncertain, instead of waiting for things to get back to “normal”. Our pre-COVID “normal” was characterized by an inequality crisis within a climate crisis and fighting to restore that world will only put us further behind.

That’s the message coming from environmental and social justice activists right now, such as those calling for a People’s Bailout and a Just Recovery from the coronavirus pandemic. Some sectors of the business community are calling for a Clean Reset, although without the same focus on inequality.

Whatever it’s called, it is essential that we put the focus back onto what we can do collectively to protect the environment and head off the climate crisis. We may never have an opportunity like this again.

Hadrian Mertins-Kirkwood is a senior researcher on international trade and climate policy for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow Hadrian on Twitter @hadrianmk.