Last week’s national jobs report may have included some shocking numbers but looking more closely at the data shows that the Canadian labour market has been on a strong upswing over the last 12 months.

With attention grabbing headlines like: Canadian economy loses 88,000 jobs in January and Don’t panic: Canada sheds 88,000 jobs in January, biggest decline since 2009, you couldn’t be blamed for feeling like Canada is on the precipice of a jobs decline, but there is so much more going on than the attention grabbing headlines can portray.

Monthly data are volatile

First and most important to remember is that the labour force survey collects jobs report data on a monthly basis, producing fairly volatile results. And while the numbers are indicators of what may be happening in the labour market—one month of data does not a trend make.

Last week, the monthly jobs numbers showed a decline of 88,000 jobs in the month of January prompting one headline to shout that this was the biggest monthly decline in 9 years. But looking at the trend on a 3- or 12-month average basis shows similar job trends to last year. Year-over-year job growth in the month of January was the smallest since (wait for it…….) April 2017. The 3-month average job growth was the smallest since October 2017, again a relatively short time ago.

In fact, even with the January decline, annual job growth on a percentage basis is higher last month than any month in 2014, 2015 or 2016.Some headlines have tried to make hay out of the fact that the largest (monthly) jobs decline was in Ontario. The thing is Ontario also has the largest labour force of any province in the country so it makes sense that the raw numbers show larger movements in the data. However, on a percentage basis, the decline is not nearly as dramatic. New Brunswick’s monthly numbers showed a 1.7% decline in employment (and a year-over-year 1.1% increase) while Ontario posted a 0.7% decline. Manitoba came in third with a 0.56% decline. The general consensus among economists regarding what effect the minimum wage increase had on the labour market in Ontario is to say we have to wait and see.¹

What’s more pertinent than the monthly numbers is a look at what has happened in the labour market across the country in the last 12 months.

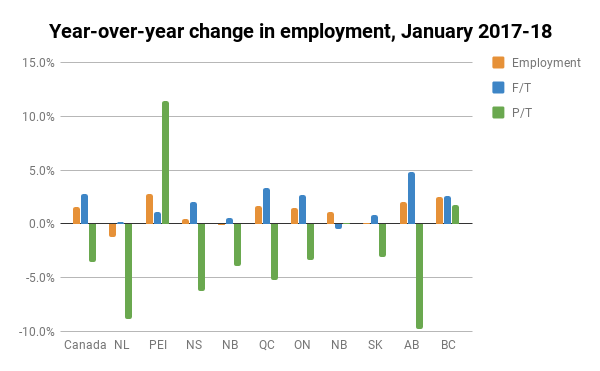

Employment gains strongest in higher minimum wage provinces

Overall, Canada saw a year-over-year increase in employment of 1.6%. That included a 3.5% reduction in part-time work and a 2.8% increase in full-time work. A similar trend of declining part-time work and increasing full-time work is evident in 8 out of 10 provinces. Prince Edward Island is the only province to see a larger increase in part-time work than full-time work (the largest increases in employment in PEI were in the construction industry and among business, building and other support services). Alberta saw the largest decline in part-time work at (-9.7%) and the largest increase in full-time work over the year. Incidentally, Alberta increased its minimum wage to $12.20 on October 1st 2016 (and to $13.60 on October 1st, 2017) giving the province the highest minimum wage in the country for the full 2017 year.²

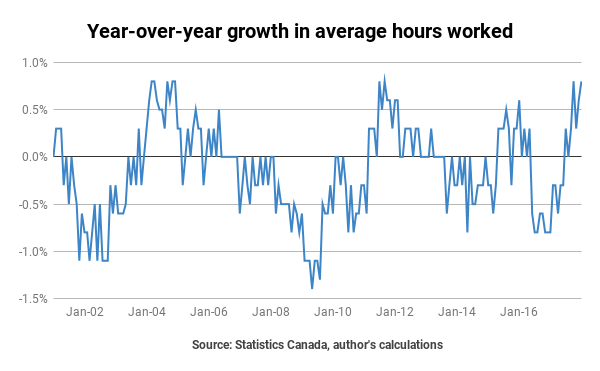

Average hours worked is on a strong upward trajectory

Not only are there more jobs since January 2017 but average hours worked is growing too. Average hours worked has been on a strong upward trend over the last year—growing 0.8% in January 2018. At the industrial level, growth in average hours was strongest among other services, information, culture and recreation, and health care and social services.

At the provincial level, Alberta, Quebec and PEI led the pack in growth of average hours worked. Overall every province with the exception of Manitoba (-0.8%) and New Brunswick (no change) saw increases in this indicator.

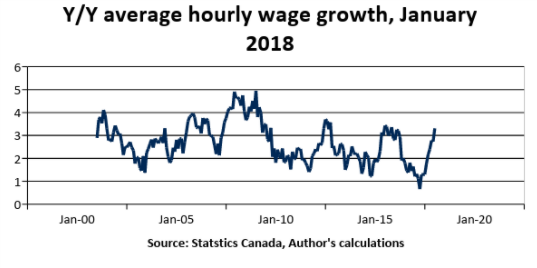

Average wage growth showing strong year-over-year gains

At 3.3%, average hourly wage growth (aggregated over all industries and ell employee types, from management to new entrants) marked strong gains year-over-year. The highest gains were evident in Finance, Insurance, Real Estate, Rental and Leasing while the industries with the smallest gains included manufacturing and education at 1.8% and 0.8 percent respectively. Overall, Canada’s average wage growth has been weak since the 08-09 recession. The country saw declining wage growth from the end of 2015 through mid-2017. The strong upswing in the last 8 months does not reverse the weak wage growth trend but does pose the possibility that there is light at the end of the tunnel.

If the labour market continues to tighten as it did over the course of 2017, it is predicted that wage growth will continue to strengthen as employers have to compete for workers in a more competitive environment where supply is closer to meeting demand and workers have more power to demand higher wages and better working conditions. Here’s hoping that theory rings true.

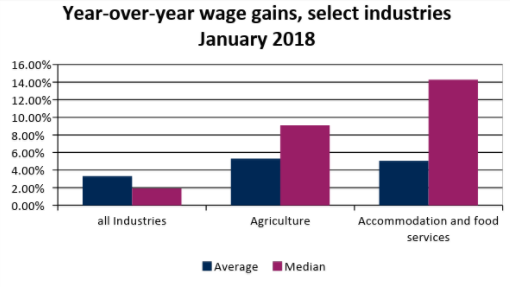

Chart to watch: median wage in low wage sectors

On average median wages have tended to grow at a slightly lower rate than average wages. This is often true in the aggregate as well as industry level. When median wage growth does outperform average wage growth, the differentials between the two tend to be quite small.

In January, low-wage sectors bucked that trend in a big way. At the industrial level, the accommodation and food services and agriculture industries have some of the lowest median wages. The median wage in accommodation and food services hovered around $12.75 last year. In January, the year-over-year increase in the median wage for this sector was more than 14% to $14. The agriculture industry saw a substantial increase in the median wage as well, increasing by 9% from $16.50 to $18 between January 2017 and January 2018. As provinces across the country have been increasing the minimum wage and some are implementing plans to move to $15 an hour, the median wages in these two industries are important indicators to keep an eye on.

This is exactly what a higher minimum wage is designed to accomplish: lifting the floor for workers who are experiencing extremely low-wage work.

------

Canada’s labour market has been on a positive trend for the past 12 months. The unemployment rate is relatively low, wages have grown, hours worked has increased and the economy has seen an employment increase of 1.6% and traded part-time jobs for full-time jobs.

Last week’s jobs numbers, though certainly alarming on the surface, do not provide enough information to say whether or not the trend has been bucked or if the numbers are just the same continuation of volatility that is always present in the labour force survey.

¹ See last week’s post from Sheila Block and David MacDonald for more information on the changes in Ontario’s labour market.

² See Ian Hussey’s recent work outlining the effects of the minimum wage increases in Alberta in the Globe and Mail for more information on Alberta’s experience with raising the minimum wage.

Kaylie is an economist working in the research department at Unifor. Follow her on Twitter @KaylieTiessen.