It’s been a chaotic year for public education in Ontario. And for all of us who benefit from a high quality and publicly-accountable system, the stakes are high—particularly for our youngest and most vulnerable.

Given what we know about the tremendous societal and economic benefits of investment in public education, the nature of these changes have more than a few advocates who believe in evidence-based decision making scratching their heads.

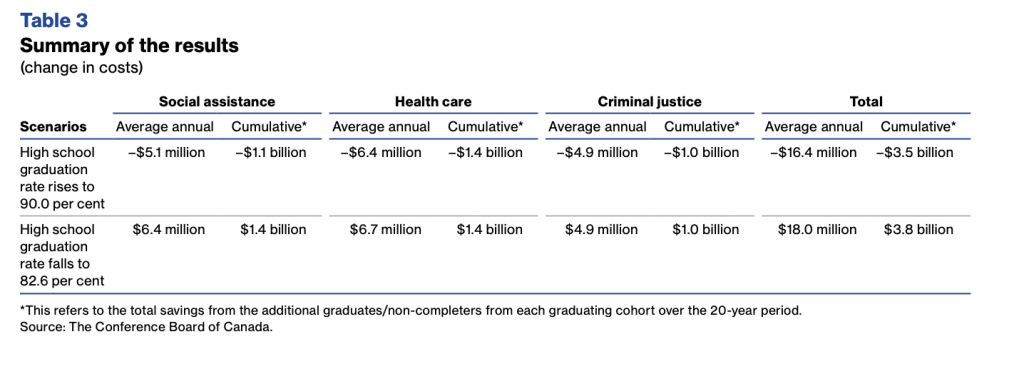

The Conference Board of Canada recently released an analysis of the benefits of investing in public education, and determined that for every dollar invested, the return was $1.30. Furthermore, their economic model suggested that current cuts were likely to result in a decline in graduation rates from the current 86% to 82.6%, at an additional cost to the economy of $3.8 billion. In contrast, if graduation rates were to increase to 90% it would result in a cumulative savings of $3.5 billion to the provincial economy.

The economic case (let alone the social or justice-based one) for investment in public education is definitive. But clearly these cuts, counterproductive as they may be, still find some popular support.

The economic case (let alone the social or justice-based one) for investment in public education is definitive. But clearly these cuts, counterproductive as they may be, still find some popular support.

To understand who these cuts and priorities are speaking to, and refocus the conversation on a collective vision of the public good that’s actually about progress, we must examine the narratives being used to justify changes to the education system that seem so counter-intuitive. There’s overlap and some contradictions, of course, but here’s a look at three of the most prevalent narratives.

- Treat adults like adults.

This narrative—you know best how to spend your money—helps justifies the voucher-type funding models for autism services and child care which have been recently implemented and pull public money out of the public system by encouraging private options. This generally means providing less funding than is required to meet kids’ needs, and often less funding altogether.

More of this narrative is found in the attacks on seniority protections in the education sector (Regulation 274), and in recent public sector wage caps, as part of a broader anti-union sentiment. Why should labour standards get in the way of being able to hire the perfect person for the job—who just happens to be your nephew? If you didn’t get paid sick days and benefits, why should anyone else? Why should people who spend their day with kids—not operating heavy machinery—get regularly negotiated pay increases when you have to ask for a raise (and risk getting laid off in the process)?

But as destructive as this narrative is, it plays on people’s desire to think of themselves as self-made, capable and self-sufficient. And it benefits from decades of neoliberal governments across the political spectrum who repeatedly undermine the role of progressive taxation in paying for the services and programs from which we collectively benefit. Any government that boasts that they are bringing “tax relief” to voters is setting the table for much more draconian service cuts down the (toll) road.

- Don’t trust anyone under 20.

This fear is infused into the so-called Parents’ Bill of Rights. It’s there in the push for financial literacy (which actually began under the previous provincial government) where kids are expected to learn about separating “wants” from “needs” and “chequing” from “savings” without delving too deeply into the racialized or gender pay gap or precarious workplaces that labour legislation rollbacks will worsen.

It’s there in the stated need to make sure we know what kids are learning—and what teachers are teaching, or should be capable of teaching...even if they never actually have to teach it.

And it’s definitely there in the controversy about the sex ed component of the HPE curriculum—a manufactured controversy that has very real negative ramifications for all kids in today’s world, but especially those who are marginalized.

The “toughening kids up” rhetoric took on bizarre proportions when the minister of education argued that class sizes weren’t actually getting “bigger,” they were just being “right-sized” to correspond to those in other provinces (which they don’t). The minister assured the public that, in response to alleged concerns from corporate Ontario and university presidents, kids would learn “resilience” through less one-on-one time with educators and education workers. (Resilience that private schools accomplish through smaller class sizes, flexible learning and a well-heeled network of “it’s who you know.”)

- Democracy is expensive and inefficient.

The chopping of Parents Reaching Out grants was an example of targeting a relatively small pot of money that had a huge impact—money earmarked to facilitate better engagement, awareness and outreach between parents and school boards. Tangible evidence of how boards work with parents directly undermines the argument that those institutions are clunky, expensive and irresponsible when compared to this government’s preferred method of public engagement.

Because it’s not as if this government doesn’t want to hear from parents—they hold telephone town halls and online consultations at the drop of a hat, and the premier is very fond of telling people to just text him. That’s how much of a regular guy he is.

But here’s where it gets complicated: the results of thousands of opinions, expert advice and testimony taken into consideration through formal Health and Phys ed consultations? Bad. The results of government facilitated online and telephone consultations? Good. Unless they’re not. Then they’re the result of a coordinated effort by “certain groups”, and to be ignored; in spite of parents and teachers panning the standardized testing administered through the Education Quality and Accountability Office (EQAO), the education minister’s response was to double down on the need to fix rather than eliminate the tests (and to appoint a failed party candidate as full-time chair).

That’s the thing about replacing formal processes—including consulting Indigenous communities before rewriting curriculum, for example—and democratic institutions with a cell phone or laptop. There’s a tremendous amount of work necessary to make sure everyone has equal access—not just those whose calls are returned—and that the results don’t have to be ATIP’d and then, if inconvenient, deemed unrepresentative of what the government insists the public really thinks.

Mobilizing class(room) consciousness

When assessing educational policy priorities, we need to keep these narratives in mind. It’s hearkening back to a simpler, highly meme-able “when we were kids” time, when teachers “easily” oversaw classes of well over 50 students; when kids were taught the value of a dollar (which is coincidentally what their father—who didn’t need sick days—supported their family on for, like, a week); where workplace standards and ADHD and peanut allergies were a figment of some latte-drinker’s imagination, or evidence of overly-coddled children.

It’s an imaginary past and an equally impossible present. But public education advocates need to remember that turning back the clock to just before the latest round of cuts is not a solution either. Too many kids and communities were not served as well as they should have been by the system, even at what some might consider its high point. If we are to provide all kids with the tools to change the world for the better and not simply accept what we acknowledge is not good enough, progress must be ongoing. And public education advocates must be unapologetic in our defense of it for all kids—not just those whose needs are more easily met, or whose parents can navigate the system.

To protect and enhance public education, economic validation like the recent Conference Board report is important. But the social returns it facilitates and the community connections it represents are equally if not more significant.

The good news is that, like many programs with broad community visibility, public education actually provides a number of opportunities to disrupt individualistic narratives, offering undeniable proof of how cutting services and reducing course selection impacts all kids; how not meeting the educational and social needs of one child will affect other kids in that classroom; how mandatory e-learning is not a workable option for thousands of students.

Parents know that larger classes are not about resilience—they make it harder for educators to teach and for kids to learn because the focus becomes crowd control, particularly as other educational supports are cut. This hurts all kids, but particularly the most marginalized. And while not all kids have the same educational needs, a parent’s desire to have their child’s needs met—and the desperation knowing that, due to cuts, they won’t be—is virtually universal.

Public schools offer almost unlimited opportunities to build and reinforce empathy and compassion because they are inherently about providing collective opportunities for individual kids to thrive in the company of their peers. And even those people only tangentially engaged with the system know it takes experience, a willingness to listen, long term thinking, and adequate resources for this to happen.

This acknowledgment, and this basis for connection, is not just powerful, it’s practical. Because parents know when it comes to what they want for their kids, and what is needed to care for them, it’s about not just surviving, but thriving. And not only does this aspiration unite people across experiences and communities, it undercuts the individualistic narratives that so many current political stunts are designed to appeal to.

Which makes education not only fundamental—it makes it, by design, necessarily inconvenient to narratives that are designed to lower expectations of what we can accomplish collectively.

Excerpts from this commentary were adapted from an earlier speech. Erika Shaker is Director of Education and Outreach at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and on Twitter at @ErikaShaker.