France and Québec have sealed alliances in the past to defend the principle of cultural exception. It essentially aims at limiting the effects of globalization within the cultural industry, already under anglo-saxon domination. State funding of the film industry has sparked a number of debates within both societies. We shall first identify what triggered these controversies on each side of the Atlantic before turning our attention more closely to the various issues debated in Québec.

France and Québec have sealed alliances in the past to defend the principle of cultural exception. It essentially aims at limiting the effects of globalization within the cultural industry, already under anglo-saxon domination. State funding of the film industry has sparked a number of debates within both societies. We shall first identify what triggered these controversies on each side of the Atlantic before turning our attention more closely to the various issues debated in Québec.

It is worth first remembering that, in 2012, the people of both France and Québec rid themselves of right-wing governments and replaced them with centre-right (or left-wing neoliberal) political parties. In both cases, a fierce debate regarding rich tax exiles ensued.

In France, the controversy led Gérard Depardieu to play the pathetic role of the poor overtaxed rich man who has no other choice, we are meant to believe, but to live in exile. Complaining that the new François Hollande government had humiliated him, the famous French actor took refuge in a democracy where “success, creation, talent, anything different” are not “grounds for sanction”, i.e. Russia.

In Québec, the PQ government was initially resolved to increase taxes for the wealthy, but that only held for a few days. Soon enough, Minister of Finance Nicolas Marceau returned to being “reasonable” and limited the scope of a measure which would have rendered income tax more progressive.

However another debate was opened up on both sides of the Atlantic in the wake of Depardieu’s follies: the one regarding film funding. Producer François Maraval stepped into the polemic in which the Russophile actor was already bogged down and denounced French actors’ excessive pay.

According to the figures he disclosed, a well-known French actor would receive a fee between €500,000 and €2 million when shooting in France, but would generally settle for a much smaller fee, between €50,000 and €200,000, when he appeared in an American movie, though the market is considerably larger.

Maraval claims that it is futile to place the blame on actors, but urgent to change the system which makes possible such excess. The money being pumped in and directed to renowned French actors comes from the indirect subsidies of private TV channels, he says. In France, it is mandatory for “television services” to invest 3.2% of their sales figure in film production, a legal disposition which stems from the idea of a “cultural exception”.

Producers absolutely have to submit themselves to the requirements of this unusual source of funding. Otherwise there would not be enough money to bring film projects to fruition. The biggest names in the game must be cast so that once a movie leaves the big screen and appears on television, audiences tune in.

Producer and distributor Maraval considers that though TV channels’ contributions should not be abolished, actors’ income must be capped. If they are not, movies will keep on costing too much, he believes, and even French films which are met with great success will still fail miserably from an economic standpoint.

Just as Depardieu was moving East to Mordovia, where he will peacefully continue his “personal degeneration” as Mordovian minister, ironically nearby the prison camp where is held one of the Pussy Riot singers, the debate regarding film funding travelled West and entered Québec.

In the past, Québec has developed policy to support the cultural scene in the name of the principle of cultural exception and film industry support was considered within this context. In the last year, some have put into question this approach entirely.

Mr Vincent Guzzo, president of both Cinémas Guzzo (a greater-Montréal mainstream movie theatre chain) and the Association des propriétaires de cinémas du Québec (APCQ), first expressed concerns about Québec cinema at the end of 2012. Mr Guzzo renewed the attack in 2013, armed this time with a poll which allegedly proved that Québec movie goers wanted to see more jokes on the province’s silver screens.

According to Mr Guzzo, the problem with Québec movies came from this incurable propensity to produce “whiny” movies instead of movies “people want to see”. That, at least, is the line of argument he was pursuing in January in the capital’s tabloid, the Journal de Québec:

“The people of Québec, they say that they’re sick and tired of their everyday problems and preoccupations and, when they go see a movie, it’s to be distracted and to forget about their daily lives for two hours. […] Too many similar movies are being made. We’ve forgotten that cinema is a popular art form. It’s neither a painting by Picasso nor the Grands Ballets canadiens [Montréal’s ballet company].”

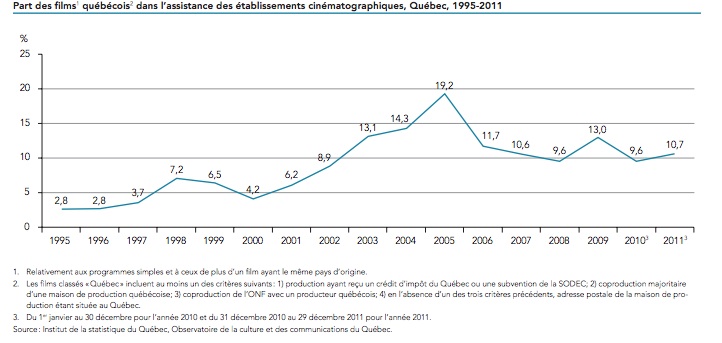

Vincent Guzzo rested his crusade upon the 2012 sales statistics for Québec cinema and its 4.8% market share, the lowest percentage since 2000. It is indeed much lower than the 13% achieved in 2003, the year of the irresistible Seducing Dr Lewis and the unstoppable Barbarian Invasions. But it is also twice the level of 1991 (2.7%). In any case, there is no evidence that the last year’s result is part of a downward trend.

The following graph shows how the share of moviegoers coming in to watch Québec films evolved since 1995 (the 2012 decline is missing from this graph).

Source : Observatoire de la culture et des communications du Québec, Statistiques sur l’industrie du film et de la production télévisuelle indépendante, p. 37The upward trend over the entire period is quite obvious. As a point of comparison, in Canada, the share of domestic English-language films barely exceeds 1% of the market. Maybe “whiny” Québec cinema isn’t that unpopular after all?

Many stakeholders stepped up to the plate and replied to the president of the APCQ. Amongst these, director Philippe Falardeau (Oscar nominee Monsieur Lazhar) responded more specifically to the accusation of wasting “taxpayer money” in “grant movies that are always complaining about something.” His rebuttal was rigorously logical: (1) it’s impossible to predict what will become a commercial success (and thus what “people want to see”), (2) big productions are not profitable even though producers and distributors earn a lot of money, and (3) all movies receive grants, from the smallest to biggest productions, and sometimes, it’s the smaller productions that end up costing less to the taxpayer.

From a strictly financial point of view, he adds, Mr Guzzo’s logic would have led to make the mistake of refusing to fund the scenarios of Incendies and Monsieur Lazhar, two projects which ended up being lucrative. And that does not even take into account the fact that Québec cinéma is far from having wasted its year 2012 by standards which lie beyond the box-office. Indeed, the last year could even have resulted in a greater international esteem.

Marc-André Lussier, a film journalist for the Montréal daily La Presse, underscored the paradox, weakness in market share versus success in “personal” productions. The three consecutive years of Oscar nominations serve as a great proof in point, along with the log jam in good Québec movies at the Jutras, Québec’s movie awards. The celebrated Bernard Émond’s latest movie (All That You Possess) was only nominated in one category and Évelyne Brochu was not even nominated for her stunning performance as lead actress in Inch’ Allah because the competition was too strong. The same assessment applies to documentaries.

In contrast, the Société de développement des entreprises culturelles (SODEC), without being as ridiculous as Mr. Guzzo, used the term “yellow alert” following last year’s crop of Québec cinema. The public corporation had in fact already revised the evaluation criteria for films. If it had not, Rebelle, which represented Canada at the Oscars this year, would have be classified as a “failure” with its $150,000 box-office receipts.

In April, the Ministry of Culture asked SODEC to set up a working group to tackle the issues and challenges of Québec cinema. The leading figures designated to sit on the committee will have until the fall to reflect. The group’s lack of representativity fuelled some critiques whilst some regretted that the group was not mandated to thoroughly revise the Cinema Act.

Back in the days of René Lévesque and the first PQ government, Québec moviemakers thought that they could found their own variant of the Third Cinema, a sort of non-aligned cinema (independent from both Hollywood and European cinema). They were inspired most notably by Argentine filmmaker Pino Solanas. A presence of a nationalist government gave directors high hopes.

Despite a bill by Gérald Godin which intended, amongst other things, to establish a royalty on profits, threats of a boycott from the American film industry and the fast approaching elections persuaded the government not to act out and to refrain from using the tougher provisions of the new Cinema Act.

The Liberals won the following elections and, in 1986, vice-Premier Lise Bacon signed an agreement with Jack Valenti, CEO of the Motion Picture Export Association of America, yielding to the latter rights over the distribution of English-language films. This agreement sealed the end of Québec filmmakers’ dream of guaranteeing the development of auteur cinema, which becomes a secondary concern of the SODICC, the predecessor to SODEC, centered on entertainment and good old drive-ins.

Québec cinema still managed to survive, but the Valenti-Bacon agreement remains relevant to the current debate between Québec’s independent distributors and the concentration of big distributors in the wake of the recent merger between Entertainment One (eOne) and Alliance Films. The former claim that without support from the state, that essential link —distribution— would end up giving out, affecting the entire Québec production. In contrast, Seville Pictures (a Montréal-based eOne subsidiary acquired in 2007) defend themselves by ensuring that they will keep on investing in the development of Québec cinema.

To conclude, the analyses of some stakeholders calling upon Québec’s film industry to move more towards reproducing Hollywood formulas hardly hide their own interests and are show little consideration for its international successes. Québec cinema is nevertheless faced with a number of challenges and some mechanisms should certainly be revised, such as those which place control over film distribution in Québec into the hands of oligopolies.

The entire film scene, including in France, would be well-advised to keep an eye on the free-trade negotiations currently underway between Canada and the European Union, which could shortly be expanded to include the United States. Québec actually exerted pressure on France to keep an exemption in the texts of the agreement which are under negotiation. It would be surprising if the demands of film industry’s superpowers did not include dropping definitively the principle of cultural exception.

This article was written by Guillaume Hebert, a researcher with IRIS—a Montreal-based progressive think tank.