We need to break up with our current fare-based transit model and the pandemic has made this abundantly clear.

Farebox recovery revenues, also called cost recovery revenues, represent the amount of a transit system’s operating costs that are downloaded to the rider through the fares they pay. As government funding for transit systems is clawed back, the reliance on farebox recovery revenues increases.

However, this reliance is itself not without impacts. The oft cited Simpson-Curtin rule provides the rough guideline that for every 3% increase in fares, ridership drops 1%. Critics of this rule argue that it is too imprecise to capture the myriad factors that influence ridership. When the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC) increased cash fares by 54% in a single year in 1992,1 this move contributed to the loss of 15 million riders.2 However, it wasn’t the only factor influencing the decline. The TTC’s attempt to close their fiscal gap by putting increased financial pressure on its ridership exacerbated financial pressure that their riders were already experiencing due to the recession and made taking transit less accessible.

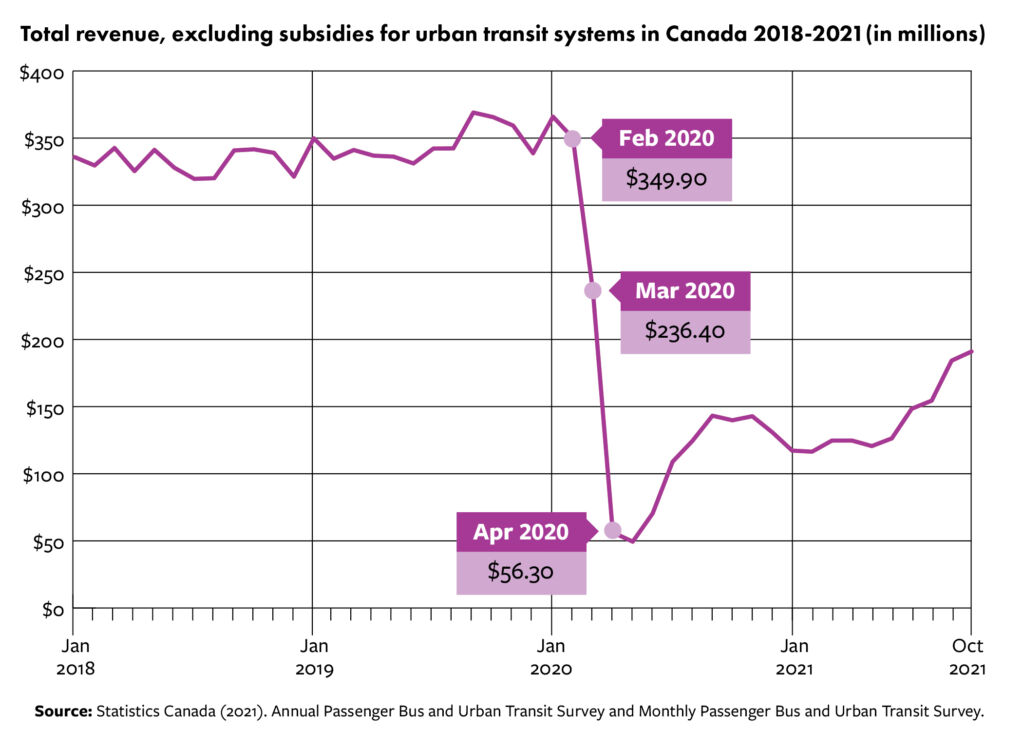

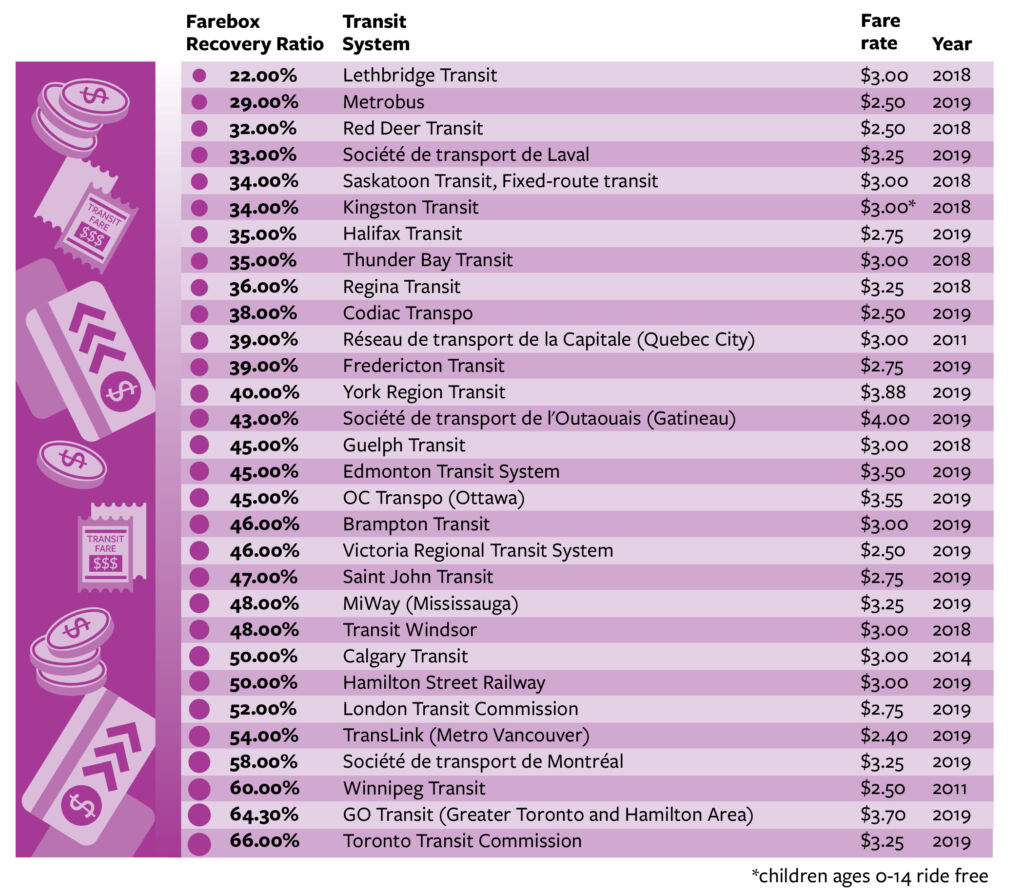

While this massive loss in ridership ought to have served as a warning to other municipalities about the pitfalls of relying on farebox recovery revenues, rider fares remain a central funding stream for Canadian transit systems. The average farebox recovery ratio for Canadian transit systems in 2019 was 51%,3 meaning that right before the pandemic hit, the majority of public transit operating costs were being covered by rider fares. This level of reliance on farebox revenues was rated by Moody’s as creating significant financial risk for transit systems.4 We don’t have to imagine what that significant financial risk looks like; we’ve seen its effects unfold in real time across Canada over the course of the pandemic.

Perhaps the most notable example of this risk is the Go Transit bus and rail system, operated by Metrolinx, which serves the Greater Golden Horseshoe region of Ontario. In the 2019–20 fiscal year, Metrolinx reported a cost recovery ratio of 64.3%. After the COVID-19 pandemic hit, the ratio fell to 10.1%.5 Go Transit lost 90.2% of its fare revenue in 2020–21, totalling a drop of $517.9 million from the previous year. While not all systems were hit as hard as Metrolinx, many faced significant ridership drop offs following the start of Canada’s pandemic experience. And though there have been some improvements in ridership numbers, they have not returned to pre-pandemic levels.

At the same time, Canada needs to be expanding its public transit systems to transition commuters out of their cars and into sustainable modes of travel. Improving transit is not possible when systems rely on fares to operate. Because of their pandemic-related declines in ridership, by 2024 the public transit agencies that serve the greater Montreal area estimate that they will have accumulated a deficit of anywhere from $716 million to $936 million. In order to address this debt, they intend to cut service by 2% each year while raising fares 4% each year, meaning that the systems could end up with a greater farebox revenue ratio than before.6

This doesn’t even take into account the amount of money that we spend collecting fares and policing our transit systems to make sure that people have paid to be there. The privately owned Presto fare card system has cost an estimated $1.2 billion to operate.7 The TTC alone reportedly spends about $10 million annually on 110 fare inspectors, and about $15 million on 120 special constables. Is this an efficient or effective use of public dollars? If we understand our transit systems as existing to help move people through cities, to help reduce the greenhouse gas emissions from personal vehicles, to close equity gaps, we can see the people using transit as deserving of service, regardless of ability to pay. If the goal is transit, let’s fund transit.

But to achieve that goal we need a different funding model. Without permanent operational funding support, transit systems remain locked in a funding ratio that leaves their budgets open to significant risk and unable to provide the low- to no- barrier access to public transit that allows Canada to reach its climate targets. It’s time for Canadian municipalities to rethink their transit funding models, but they can’t do it without the support of all levels of government.

Notes

Graphs by Katie Sheedy. Header illustration by Karen Hibbard.

1 TTC fares from 01.21.1973 to Present. (n.d.). Transitstop.net. Retrieved from http://transitstop.net/Stats/t...

2 Rusk, J. (2002, November 12). TTC warns of 50-cent fare increase. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.co...

3 The Canadian Urban Transit Association (CUTA ACTU). (2021 June). Why public transit needs extended operating support. https://cutaactu.ca/wp-content...

4 Moody’s Public Sector Europe. (2021, March 29). Structural fall in ridership post pandemic opens substantial funding shortfall. https://www.lagazettedescommun...

5 Metrolinx. (2021). Annual Report. Retrieved from: metrolinx.com/en/docs/pdf/board_agenda/20210624/20210624_BoardMtg_2020-2021_Annual_Report.pdf

6 Keep Transit Moving Coalition. (2021).Permanent operational funding. https://www.keeptransitmoving....

7 Spurr, B. (2018, Sept 7). Ontario's Presto costs soar to $1.2 billion. Toronto Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/g...