I was really hoping the recent release of Census data would bring good news: wage gap closed! Racial discrimination gone! Equality achieved!

Not so much.

Gaps in pay for women and racialized groups persist. Ditto for immigrants and Indigenous peoples.

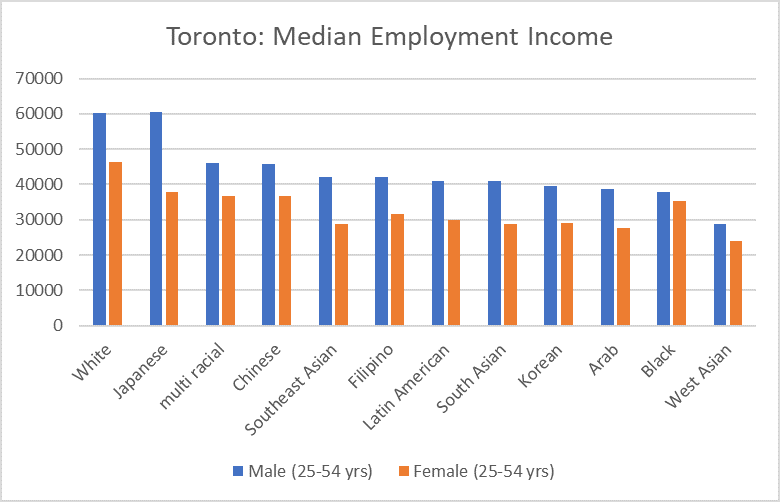

Consider Toronto, Canada’s largest city and one of its most diverse. More than half of Toronto’s population are immigrants. Exactly 50 per cent of the city’s population identifies as a visible minority. Maybe in the next Census, Statistics Canada will swap “visible minority” for “racialized,” seeing as 50 per cent is not a minority.

Take a closer look below at the economic life of Toronto’s diverse population. Here’s what you get: the wage gap is there for every group of women—both when compared to the paycheque a white man brings home and when compared to men within the same group. White women earn more than any other group of women (but still 22 per cent less than white men).

One in six Torontonians is South Asian. South Asian men make only 68 per cent of what the average white man makes in the city. South Asian women make less than half that amount. And while your jaw is dropping and ire rising, consider also what the city and its women are missing out on in economic terms. If those same women were making the same salary as their white male peers (and I only looked at women who had employment income and were between the ages of 25 and 54 years), they would have added $6.8 billion more to Toronto’s economy and their own bank accounts in 2015. That seems like a deficit worth worrying about.

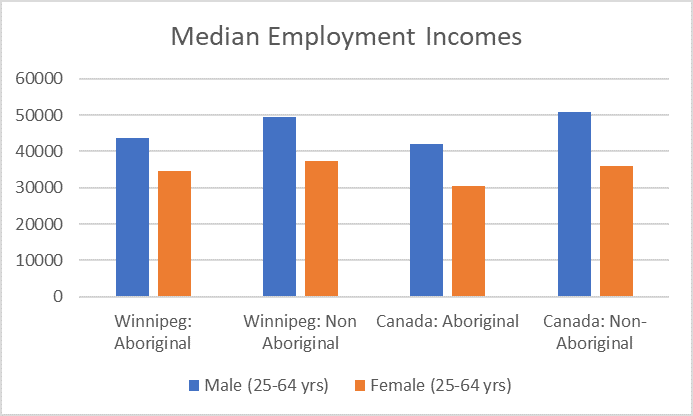

As much as I enjoy picking on Toronto, it seems only fair to point out that other cities don’t fare any better. Winnipeg has one of the largest Indigenous populations among Canadian cities; more than one in ten Winnipeggers is Aboriginal. Aboriginal men see a 12 per cent shortfall in their wages compared to non-Aboriginal men. Aboriginal women bring home 30 per cent less than non-Aboriginal men and 21 per cent less than Indigenous men. Which is better than the national average, but maybe not something you want to brag about.

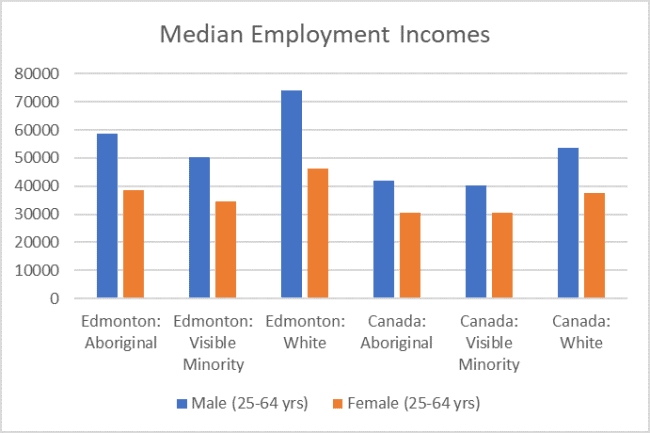

Edmonton is the best city in Canada to be a man, as far as employment incomes go (see guys, I’m keeping an eye out for you). That is, unless you’re not white. One in four Edmontonians identifies as part of a racialized group. Racialized men bring home nearly $25,000 less each year than white men and racialized women earn less than half what white men earn. Less than half. 46 per cent to be exact.

For the 5 per cent of Edmonton’s population that is Aboriginal, the picture is better, but only in comparison to really bad. Aboriginal men earn 87 per cent of what non-Aboriginal men do, and Aboriginal women earn 57 per cent of what non-Aboriginal men bring home and 65 per cent of what Aboriginal men earn.

There are other forms or discrimination that are not captured by the Census, but which have been shown by smaller studies to have a negative economic impact. A large-scale survey of trans folks in the United States found patterns of discrimination in hiring, firing and pay for the trans community. This is a pattern which a smaller study based in Ontario echoes. An analysis of income data for gay men and lesbian women finds that although as a group they have higher educational attainment levels than their straight peers, gay men in particular earn less on average than straight men. Lesbian women and straight women also earn less than both gay and straight men.

Women with disabilities continue to be among the poorest in the country. People with disabilities report employment as their main source of income, yet they continue to face high rates of under-employment and low levels of earnings. People with disabilities in Canada earn 56 per cent of what those without disabilities earn.

Now I know you’re thinking, this is all just because some people are working full-time and others aren’t. Or maybe it’s a difference in education. Plus babies. This is the beautiful and terrible thing about Census data. You can account for all of those variables. Turns out, a 30 something female dentist with a university degree, working full-time full year, still earns 74 cents on the male dentist dollar. Actually, women earn less than men (working full time, full year) in 133 out of 140 occupations tracked by the Census. So unless you are a chiropractor or a food counter attendant, you are almost certainly looking at a wage gap.

One of the things that has been demonstrated to help narrow pay gaps is tracking and transparency. Because when people know they are making less than the guy next to them, they have the means to hold their employers to account. Why not consider the Census one big transparency exercise?

The numbers are there if you care to look. So is the outline of discrimination.

Kate McInturff is a senior researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. You can follow Kate on Twitter @katemcinturff.

This blog was originally published by the Canadian Women's Foundation.