Today, rideshare drivers from companies like Uber and Lyft are taking part in a global strike to protest for livable wages, job security and regulated fairs, among other demands—all taking place on the eve of Uber’s initial public offering on the stock market this week.

Back in Canada, bike couriers for the Toronto-based food delivery app Foodora have been working with the Canadian Union of Postal Workers in a bid to unionize, citing a lack of basic employment benefits like employment insurance or CCP/QPP premiums (more in-depth analysis of Toronto’s sharing economy can be found in this report from my colleagues at CCPA-Ontario).

“We took a vote to go out on this strike as an act of solidarity,” says @bhairavi_desai, New York Taxi Workers Alliance executive director, from the #UberLyftStrike at the Charging Bull. “But also to demand that Uber and Lyft drivers should be guaranteed 80 to 85% of the fare.” pic.twitter.com/11uKcbMffj

— Tyler Sloan (@tesloan) May 8, 2019

Rapid changes to the economy, including the rise of gig work associated with on-demand service apps, has increased interest from certain policy makers, as well as tech leaders, in the concept of basic income.

Let’s explore that topic further.

Back in December, Jordan Press at Canadian Press dragged out the admission from Minister of Families, Children and Social Development Jean-Yves Duclos that the Liberals might “one day” enhance federal transfers to cover Canadians that get little from today’s income transfer programs. Those who receive very little today are adults who don’t have children and aren’t yet seniors. Providing more transfers to low income people in those categories would move us further towards a basic income in Canada.

Duclos has long maintained—and I agree—that we already have an extensive basic income system in Canada. Once you combine federal and provincial transfers to people without earned income, a floor on income is created. This is before factoring in social assistance and contributory programs like the Canada Pension Plan or EI. You get these transfers merely by being a citizen. My full report on the issue is available here.

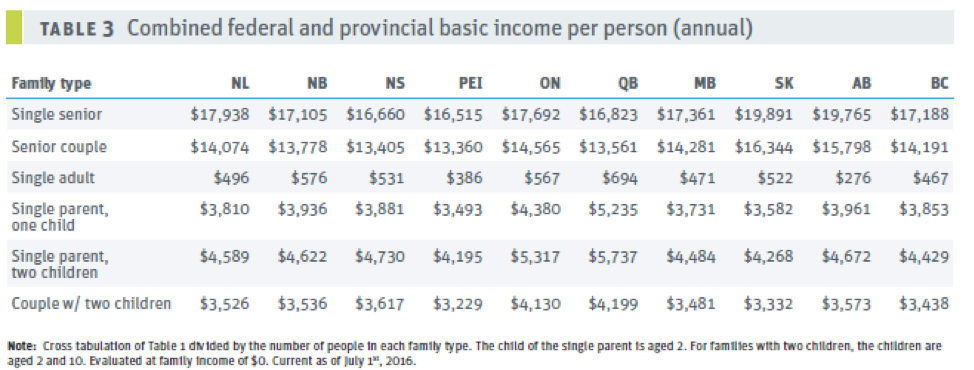

The seniors’ basic income consists largely of Old Age Security (OAS) and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS). For families with children, it’s largely the Canada Child Benefit. There are also refundable tax credits for sales and carbon taxes, although these are smaller. Additionally, provinces provide equivalents to federal programs, but these are also small. As you can see from Table 3 that I from the aforementioned report, basic incomes in Canada vary a lot depending on the family type and province, but generally seniors have the highest basic incomes followed by families with children. The lowest basic income is for adults, which can be as little as $276 a year in Alberta. You’re not going to live off of that for very long.

Note: this is current as of July 2016, carbon rebates rolling out shortly will alter this picture somewhat.

I’m always asked: “Do we need a basic income in Canada?” Well the trouble is that we already have one, well we actually have several. Two better questions are

- How can we improve pre-existing basic incomes?

- Is a basic income always the answer to low incomes?

For the first question, I think there are some obvious ways that we could improve the basic income programs in Canada (several of these items are in our Alternative Federal Budget). An obvious place to start is with adults who aren’t seniors and don’t have kids. No doubt we can also be more generous in the GIS and CCB, particularly for lower income families. But when it comes to adults under 65 without children, their basic income today is almost nothing. One group in particular, adults between 50-65, would particularly benefit from more support. Poverty rates spike in this age range as people stop being able to work either because they become injured or sick, or their spouse does, and they have to stop working. These people have few supports other than social assistance, which also spikes in these ages. Paradoxically when they turn 65, poverty rates drop significantly as they gain access to seniors’ programs.

For the second question, remember that basic income is frequently being presented as the solution to the gig economy (often by Silicon Valley tech giants themselves). I actually think this is a very dangerous flip-side to the basic income argument. It’s concerning to think that as people are forced to work part-time with no benefits and no rights, a basic income will catch them on the way down. The fact that “sharing economy” companies don’t abide by basic labour laws like paying EI or CPP or a minimum wage shouldn’t be “solved” by a basic income. Rather, they should be solved by enforcing the labour laws. Just because they have an app doesn’t give employers a license to treat employees badly, nor does it mean governments should cover for them with a basic income program. Basic income isn’t going to help you get a job or give you a raise, but a tight labour market might.

That’s why basic incomes need to be paired with commitments to full employment. Government policies that enforce workers’ rights, while keeping unemployment low and wages rising are more likely to serve working age adults. The proportion of prime working age Canadians with a job has never been higher. We are at full employment, or the closest we’ve been in almost half a century. But this hasn’t led to record high wage growth yet, which it should. Now it’s time to figure out how we can push wages up, while improving basic incomes. The two go hand in hand.

David Macdonald is a senior economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Follow him on Twitter at @DavidMacCdn. His 2016 report, A Policymaker’s Guide to Basic Income, can be found here. The report "Sharing economy" or on-demand service economy? A survey of workers and consumers in the Greater Toronto Area from CCPA-Ont is available online.