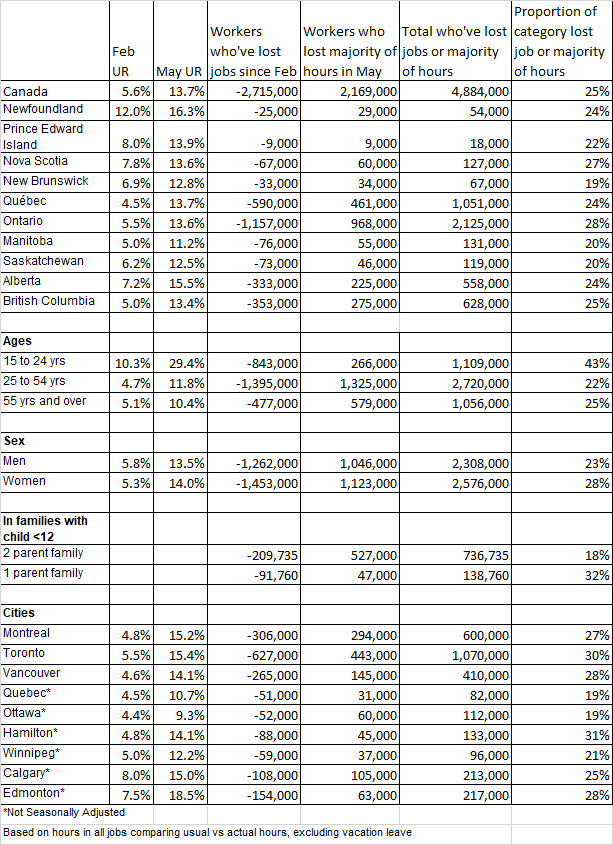

Labour Force Survey key facts:

- In May, 2.7 million people lost their jobs and another 2.2 million had most of their hours cut compared to February.

- Since February, 4.9 million people have lost jobs or had most of their hours cut, an improvement from April when it stood at 5.5 million.

- 43% youth (aged 15 to 24) lost jobs or most of their hours since February.

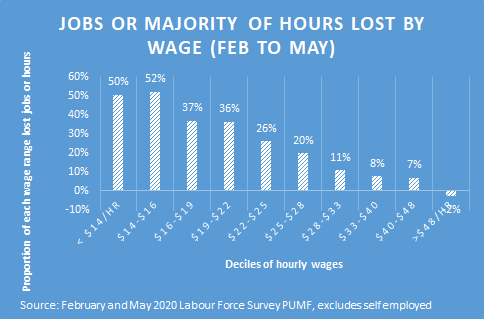

- Half of workers making under $16/hr lost their jobs or most of their hours, while those making over $48/hr have seen job and hour gains.

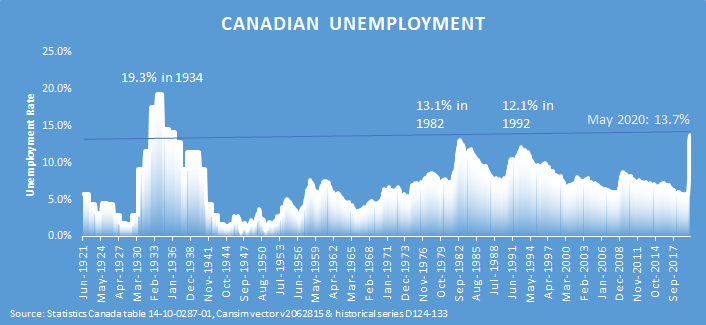

- Unemployment is the worst it’s been since June 1936.

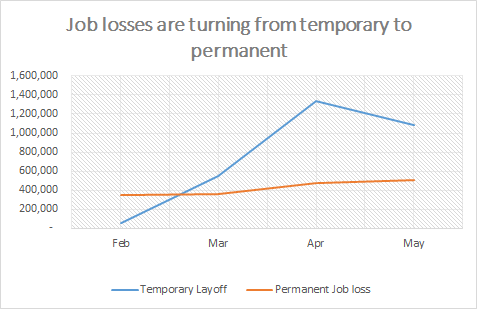

- Most layoffs remain temporary with relatively few converting to permanent job losses.

The full impact of COVID-19 is reflected in today’s May’s Labour Force Survey: the loss in jobs and hours looks like the Great Depression (June 1936 to be precise).

Since February, 2.7 million Canadians have lost their jobs outright. Another 2.2 million lost between 50% and 100% of their working hours. In total, 4.9 million Canadians have lost either their jobs or at least half and possibly all of their hours.

These shocking, Depression-level job impacts were required to flatten the curve of COVID-19’s spread so that the virus did not totally overwhelm our health care system.

However, the economic burden from this shock to the system has not been shared equally.

Half of workers making under $16 an hour, and over a third of those making between $16 and $22 an hour, have lost their job or at least half their working hours since February. Workers at the very top of the hourly wage category, on the other hand, have seen job and hour gains. This is a similar trend as was evident in April.

By and large the layoffs since February have remained temporary. There has certainly been an uptick in permanent job losses since February, rising from 351,000 to 502,000 in May. The May figure is roughly 200,000 higher than it was in May 2019, nonetheless, permanent losses aren’t rising dramatically. As employment started to recover last month, it was temporarily laid off employees who were called back to work.

The initial closure of sectors deemed non-essential included food, hospitality, a portion of retail, and secondary health care. Since women are much more likely to work in these sectors than men, particularly on the frontlines, they experienced the greatest impact in the first phase of the economic shutdown.

By April, the data reflected the impact—disproportionately born by men—of the shutdown on construction and manufacturing, which roughly equalized the overall job and hour losses between men and women.

However, the May data demonstrate that as jobs returned, they’re following a trend of first shut down, last to reopen. Men saw significantly larger improvements than women did since April. Women were the first to face mass layoffs and they now appear to be the last in the recall process.

The phased reopening in several provinces at the end of May will certainly bring some of these jobs and working hours back. But full recovery will take months, and probably years, with those hardest hit likely to experience the longest road to recovery.

A safe reopening requires a consistent and robust plan to live with and contain the spread of COVID-19, while also providing for those who need support and assistance when they are impacted by the pandemic, as patients or as workers. There are currently no such provisions in place.

Moving toward a safe reopening requires, at minimum, that we improve how we are testing, how we protect workers in the workforce, and how we support those workers who cannot return to work due to ongoing shutdowns or because their jobs have disappeared.

Adequate testing: Canada simply doesn’t have the systems in place to adequately catch and isolate new outbreaks. We aren’t universally testing high-risk workplaces, like long-term care homes, meatpacking plants, migrant worker camps, and the like. Canada isn’t randomly testing the population as a whole to determine who has the virus, who doesn’t, and who’s recovered. We’re only testing those who are already sick, the worried but well, and some health care professionals.

Worker protections: Canada doesn’t have the necessary sick leave and income supports in place to allow people to stay home, even if we could rapidly identify new outbreaks. Since we don’t have any of these prerequisites, most jurisdictions aren’t opening schools and child care centres, which forces many parents of young children to stay home. In fact, a third of single-parent families are out of work, although it’s a wonder how the 285,000 single parents who are in the workforce are managing.

Keep CERB going: CERB is the social safety net for workers who can’t return to the workplace until their jobs are safe or re-activated, or until they’re able to secure child care or schooling for their children, or until they’re well enough to work amid a pandemic. We need to keep CERB going for the moment. But soon we’ll need a modern EI replacement as this crisis continues.

The reopening in several provinces since Victoria Day and the flattening of the curve outside of long-term care facilities offer some hope in today’s gloomy statistics. However, hope is not a strategy. We need tangible plans.

Without these critical tools to limit the spread of the pandemic, and to proactively keep people and communities healthy and safe, the default position will be full provincial shutdowns again if and when COVID-19 resurges.