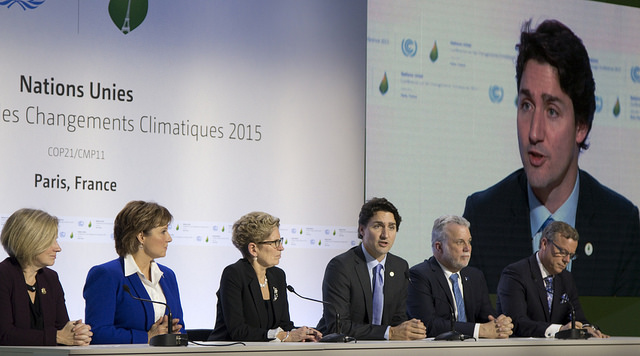

Photo: Justin Trudeau and Christy Clark at the United Nations COP 21 Climate Change Conference. Source: Province of BC / Flickr.com

Photo: Justin Trudeau and Christy Clark at the United Nations COP 21 Climate Change Conference. Source: Province of BC / Flickr.com

For decades, the urgent need for climate action was stymied by what came to be known as “climate denialism” (or its more mild cousin, “climate skepticism”). In an effort to create public confusion and stall political progress, the fossil fuel industry poured tens of millions of dollars into the pockets of foundations, think tanks, lobby groups, politicians and academics who relentlessly questioned the overwhelming scientific evidence that human-caused climate change is real and requires urgent action.

Thankfully, the climate deniers have now mostly been exposed and repudiated. ExxonMobil—a central architect and funder of the denial industry, along with the Koch Brothers—even became the focus of a US fraud investigation earlier this year, after it was revealed the company not only knew about the dangers of climate change as far back as 1977, it pioneered some of the earliest research about its existence.

Relatively few politicians now express misgivings about the reality or science of climate change (the current Republican nominee for US president being a notable exception, along with some other conservative bright lights like Sarah Palin and Canadian MP Cheryl Gallant). Our own prime minister and all Canadian premiers (except, arguably, Saskatchewan’s Brad Wall) publicly recognize the reality of climate change, and have stated in their platforms and throne speeches that they are committed to significantly reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

That’s the good news.

The bad news is we face a new form of climate denialism – more nuanced and insidious, but just as dangerous.

In the new form of denialism, the fossil fuel industry and our political leaders assure us that they understand and accept the scientific warnings about climate change — but they are in denial about what this scientific reality means for policy and/or continue to block progress in less visible ways.

In the lead-up to the Paris climate talks, for example, the Oil and Gas Climate Initiative (OGCI) issued calls not only for a global climate agreement, but also for a global carbon pricing system. The OGCI includes most of the world’s largest oil companies (Shell, BP and Total among them), so this was a big deal. But as research by the UK-based InfluenceMap uncovered, “behind the scenes, however, [these companies] are systematically obstructing the very laws that would enable a meaningful [carbon] price.”

Here at home, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP)—the most influential oil lobby group in the country—proclaims on its website that “climate change is an important global issue, requiring action across industries and around the globe.” Sounds nice and green. Yet CAPP continues to push hard for expanded oil sands production and new pipelines on behalf of its members, which include the country’s largest oil companies.

Claiming that we can take effective action on climate change and ramp-up fossil fuel production at the same time is what CCPA senior economist Marc Lee refers to as “all the above” policy-making.

It’s what former Prime Minister Harper was doing when he claimed Canada could be a climate leader while at the same time increasing fossil fuel production, so long as industry reduced emissions per unit of oil, gas or coal produced (i.e. reducing so-called “emissions intensity”).

It’s what Prime Minister Trudeau and Premier Notley are doing when they say we will have carbon pricing and various regulations, while at the same time supporting expanded oil sands production and new bitumen pipelines.

It’s what Premier Clark is doing when she proclaims BC will be a climate “leader” while at the same time pursing a ramp-up in natural gas fracking and the development of an LNG export industry.

And it’s what Canada is doing when we sign the Paris agreement on climate, while failing to adopt the stringent policies that will help keep global temperature increases to 1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels.

The “all of the above” approach is wishful thinking at best. A recent study by earth scientist David Hughes published by the CCPA and Parkland Institute found that if Alberta and BC go ahead with planned expansion of the tar sands and development of an LNG industry, it will blow our Paris climate commitments right out of the water.

On a related front, the new climate denialism operates hand-in-glove with Indigenous Rights and Title Denialism.

Like its climate counterpart, this form of denialism sees politicians claim to accept recent court rulings and the historic reality of Aboriginal Rights and Title. Indeed, our new federal government has promised to adopt the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and ensure that all its policies are consistent with UNDRIP. But again, our governments are unwilling to accept what rights and title mean in practical policy terms.

Indigenous rights denialism finds expression in particular when rights and title are at odds with the power and interests of the corporate fossil fuel sector.

We see both Indigenous rights denialism and climate denialism at play in various fights over pipelines. In the case of Kinder Morgan’s Trans Mountain project, for example, numerous First Nations along the route have firmly rejected the proposed pipeline expansion. There is clear evidence that the pipeline is also at odds with Canada’s commitment to lower its greenhouse gas emissions. Nevertheless, both federal and provincial governments remain firmly in favour.

Similarly, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers released a discussion paper earlier this year endorsing UNDRIP “as a framework for reconciliation.” The discussion paper explicitly recognizes the right to self-determination by Indigenous Peoples and the related right to free, prior and informed consent. This sounds very promising. Yet it is fundamentally in contradiction with CAPP’s support for new pipeline projects like Enbridge’s Northern Gateway, which is the subject of a legal challenge by eight First Nations.

What part of either Aboriginal Rights and Title or climate change science is confusing here? Why is this clear NO so contentious?

Talking honestly about what climate change and Indigenous rights mean for the policy choices before us is admittedly challenging. The public is nervous, and many are deeply anxious about their economic security and jobs. So the urge to take an “all of the above” approach is understandable.

But real leadership requires leading a different conversation, one where we speak frankly about the scope of transformational change that lies before us in the next thirty years.

When a friend is struggling with an addiction they cannot bring themselves to confront, true friends do not show sympathy by turning a blind eye to the destructive behaviour. Rather, a real friend makes an intervention, and tells the truth. We can acknowledge the steps our political leaders have taken towards becoming climate leaders – but we need to keep pushing them to meaningful action.

It may be difficult to imagine a world that isn’t dependent on fossil fuels, or a future where Indigenous Peoples exercise their full historic rights – and there’s no doubt it will take hard work to get there. But just as children today have never known smoking to be permitted in restaurants or driving without mandatory seatbelt laws (both changes that were fiercely resisted by industry but are now fairly universally accepted as the new normal), those born in the coming decades likely won’t know what a gas station is, except for what they see in old movies.

The reality of climate change means that one way or another, the next generation is going to live through an industrial revolution in high speed. That’s simply a fact. Our political leaders need to move past these current incarnations of denialism, and focus instead on making sure the transition can occur in a just manner.

This article is published as part of the Corporate Mapping Project, a research and public engagement initiative investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry. The CMP is jointly led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and the Parkland Institute, and is supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Seth Klein is the BC Director of the CCPA. Shannon Daub is the Associate Director of CCPA-BC and co-director of the Corporate Mapping Project.

This article was originally published on CCPA-BC's blog, PolicyNote.