1) Size matters

For my entire professional life I’ve watched the federal government shrink its contribution to the economy. That may be about to change. As the wraps come off the first Liberal budget of the 21st century, we’ll find out if the trajectory has pivoted away from “the best federal government is the smallest government.”

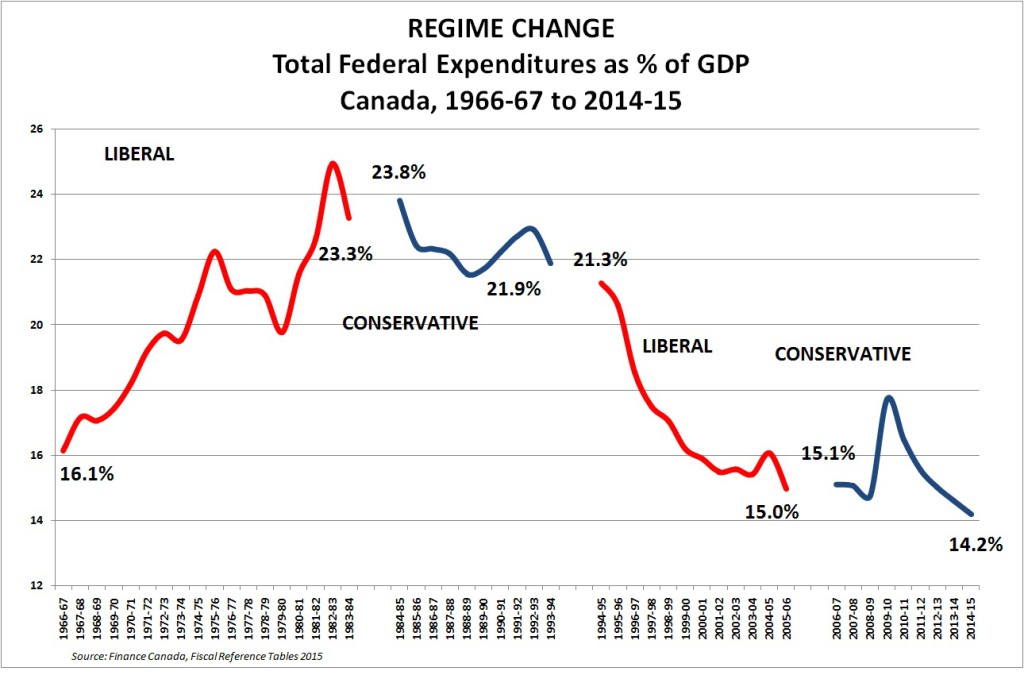

Here’s a chart that shows total federal expenditures (including debt charges, which are incomes for some) as a share of GDP, from 1966-67 to 2014-15, with Liberal and Conservative eras of federal government differentiated. The solid lines show what happened, according to fiscal reference tables. Where will regime change take us?

After expanding federal supports for health care, jobless benefits, family allowances, social assistance and post-secondary education in the 1960s and 1970s, the federal government has continually scaled back its contribution to the economy for the past 30 years, with brief exceptions in the wake of major economic recessions (1981-82, 1990-91 and 2008-9).

Today, at 14.2% of GDP, the federal government is the smallest it has been in relation to the Canadian in the last 60 years. It peaked at 24.9% in 1982-83, a combination of a large contraction of the Canadian economy and big outlays on jobless benefits.

2) It’s not just how big it is, it’s how you use it

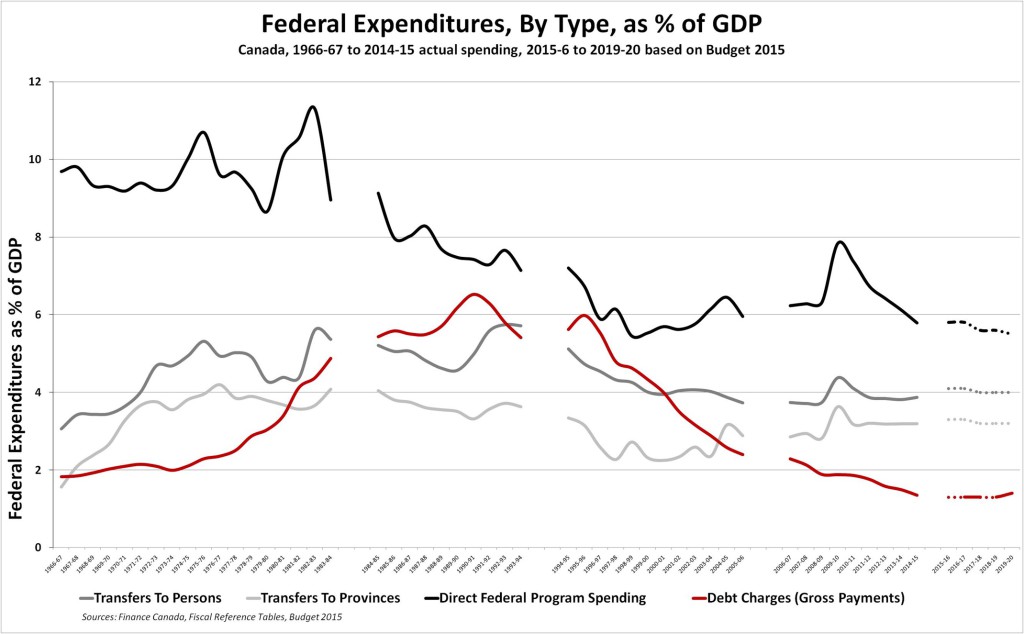

Size matters. It is unlikely we will be able to face the challenges of slowing growth, crumbling infrastructure and population aging without a significantly larger role for government in the coming years. But it’s not just how big the federal government is that matters; it’s how the government chooses to use that money.The following chart shows how different Liberal and Conservative regimes have approached both expansion and contraction of elements within the federal enterprise, such as

<li>income supports to individual Canadians (children, seniors and the unemployed);</li>

<li>supports to provinces (to provide health and education, and social programs such as welfare, in addition to fiscal arrangements that leave no province too far behind in bad economic times);</li>

<li>direct program spending (from Defence to First Nations programs, from Food Inspection to International Assistance, etc.); and</li>

<li>debt charges, covering the costs of borrowing.</li>

The solid lines show how governments have performed in each area since 1966-67. The dotted lines show where we were headed, according to Budget 2015. Where will the new budget take us in terms of our supports for individuals, for provinces and direct program spending?

3) The debt “burden”: Is what we owe or what we pay more relevant?

No federal government has had to pay lower borrowing costs for the past 60 years, a function of both historically low interest rates that have dominated economies around the world in the wake of the 2008-09 crisis, and a dogged focus on reducing the federal debt to GDP ratio since the mid 1990s.Both the previous Harper government and the federal Liberals have announced their “anchor” for future performance is reducing the federal debt to GDP ratio to 25%. To meet this goal by 2020 – a Liberal campaign promise, and as yet not ruled out by the Finance Minister as a promise to be kept – either revenues will have to increase or spending will have to be cut.

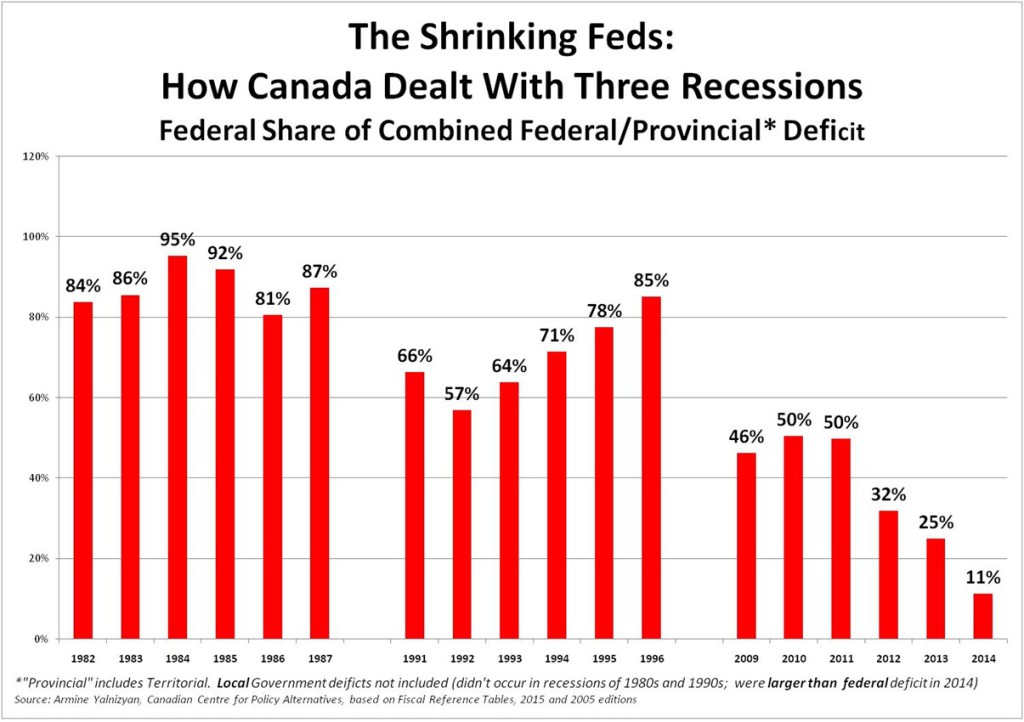

4) Debtnation: Will the feds keep passing the buck to the provinces and cities?

While the federal government has devoted much political currency to shrinking the federal debt, it has done so at the cost of bearing less of the load in the wake of the 2008-09 crisis than in any previous recession. With the federal government announcing higher immigration levels, it will need to also spend more to support provinces and municipalities on housing and transit issues to accommodate this growth, or debt at this level of the confederation will have to rise.5) Counteracting slowth: Can it be done?

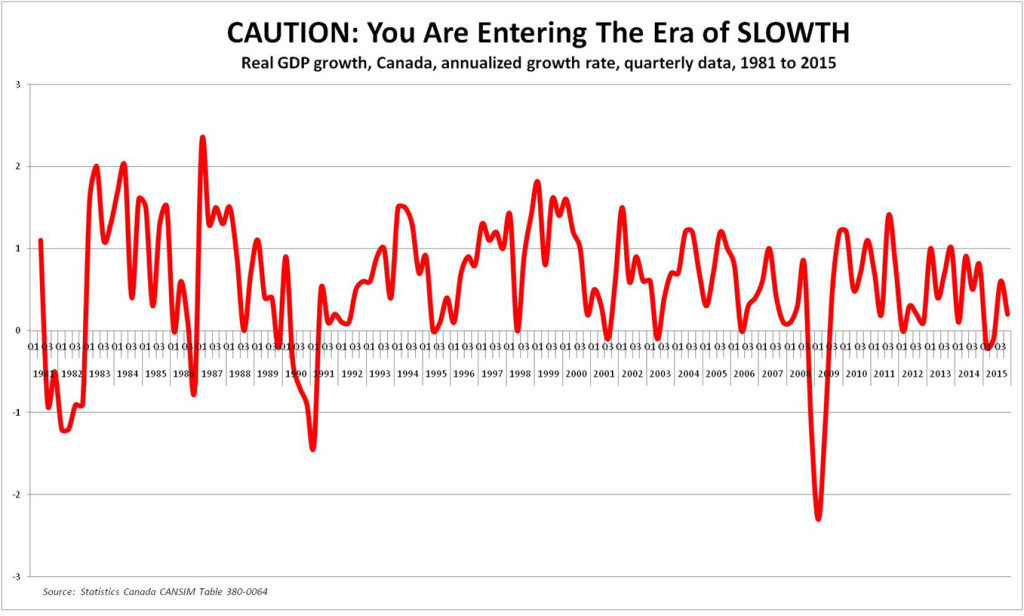

The major challenge for this budget is to lay out a plan that can spur enough growth so that temporary deficits don’t become structural ones.If government spending doesn’t unlock private sector growth (household incomes, business investment, or perhaps a windfall from exports, which no budget plan can affect in the short term) growth will not provide a boost on the revenue side of the books. In this event, either taxes will need to be raised or spending decreased to meet their stated longer term “anchor” economic indicator, a falling federal debt to GDP ratio. Either measure could further slow the economy, which is functioning closer and closer to a razor’s edge.

Like the climate change challenge, we need to both move the needle and learn to adapt to this New Abnormal. It will not be an easy or swift transition, and it will probably require a larger role of government.

Armine Yalnizyan is a Senior Economist with the CCPA. She will be in the budget lockup and following these trends. You can follow her on twitter @ArmineYalnizyan