Summary

Ruby River Capital’s NAFTA lawsuit against Canada, in response to being denied a permit to build a liquefied natural gas (LNG) project in Quebec, exemplifies the troubling excesses of investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), particularly in an era of urgently needed climate action. The case drives home the growing conflict between forward-looking, ambitious climate action and retrograde investment treaties that indemnify foreign investors from government actions that might harm their investments and future profits.

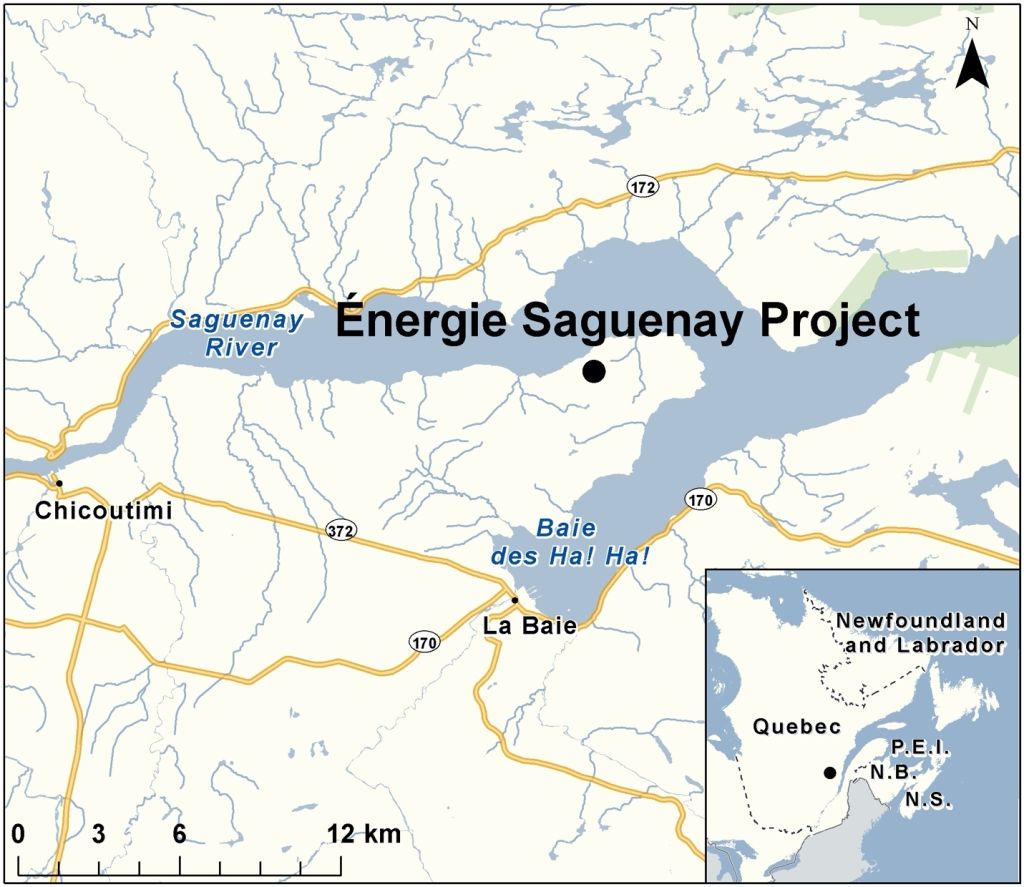

Ruby River is a Delaware-registered corporation owned and controlled by two U.S. venture capital firms. It in turn is the sole shareholder of Symbio Infrastructure GP Inc., a Quebec firm established to pursue the construction of a natural gas liquefaction plant and maritime terminal on the Saguenay fjord near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec, and a 780-kilometre spur pipeline to supply the facility with fracked gas from Western Canada. The combined projects were named Énergie Saguenay.

Though initially supportive of the project in principle, the Quebec government ultimately rejected Énergie Saguenay after a two-year environmental impact assessment panel raised concerns about increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, threats to marine mammals, and adverse impacts on nearby First Nations. A year later, the federal government also denied approval for the LNG project based on Ottawa’s parallel environmental impact assessment.

This should have been the end of the matter. But in February 2023, Ruby River sued Canada under NAFTA’s now expired investment chapter. The company claims it was subjected to “fundamentally arbitrary, procedurally grossly unjust, expropriatory, and discriminatory treatment” by the Quebec and Canadian governments, in violation of various NAFTA investment chapter protections. Ruby River initially wanted compensation of “no less than” $20 billion USD (about $27 billion CAD). While this staggering amount was revised downward in subsequent filings to the NAFTA tribunal, it is expected to still be in the multiple billions of dollars.

Sadly, it is rare for Canadian governments to take the hard decisions consistent with their ambitious greenhouse gas reduction pledges. But when elected officials find the courage to act decisively, by curtailing fossil fuel projects, it is absurd for prospective investors such as Ruby River to feign shock and indignation. It is also highly problematic that investment protections in treaties like NAFTA allow private tribunals to second guess the democratic choices of countries struggling to respond to the climate emergency.

The Ruby River case illustrates other problematic features of contemporary ISDS, including:

The rising prevalence of speculative, third-party funding of investor-state arbitration, which encourages and sustains cases that might not otherwise be viable.

The revolving door between government lawyers responsible for negotiating and implementing investment treaties and the private arbitration industry that profits from ISDS.

The chilling effect on independent arms-length environmental impact assessments when ISDS tribunals refuse to acknowledge their vital autonomy from governments.

Disdain for the legal principle of “free, prior and informed consent” from Indigenous Peoples for major industrial projects proposed on their ancestral lands.

Quebec’s independent environmental impact assessment of the Énergie Saguenay project fundamentally challenged Ruby River’s rosy environmental and business case for the LNG export terminal and pipeline. You might assume that the U.S. investor therefore has a weak NAFTA case. Unfortunately, NAFTA has already been used to successfully challenge the results of a Canadian environmental impact assessment for a planned quarry on the Bay of Fundy, and similarly outlandish cases have succeeded elsewhere under investment treaty arbitrations.

The Ruby River investor-state challenge, and cases like it, erode the key hope for decisive action to avert catastrophic climate change. That is, that citizen movements, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities can join together to press elected officials to block new fossil fuel projects and phase out existing ones. This is exactly how the Énergie Saguenay project was stopped. This remarkable, public-spirited environmental victory should be celebrated and emulated, not penalized.

It can only be hoped that the audacious, anti-democratic Ruby River complaint will prove a catalyst for Canada to finally erase ISDS from all its treaty commitments and to support international efforts to exit and dismantle the international investment arbitration system.

Key facts of the NAFTA dispute

Ruby River Capital is a Delaware-registered corporation owned and controlled by two U.S. venture capital firms. It in turn is the sole shareholder of Symbio Infrastructure GP Inc., a Quebec firm established to pursue the construction of a natural gas liquefaction plant and maritime terminal on the Saguenay fjord near the mouth of the St. Lawrence River in Quebec. The project included plans for related infrastructure needed to store gas, load tankers, and ship liquefied natural gas (LNG) to overseas markets. It also required the construction of a 780-kilometre spur pipeline from Northern Ontario to enable fracked natural gas from Western Canada to be delivered to the facility. The combined projects were named Énergie Saguenay.

In July 2021, after lengthy debate and consideration, the Quebec government rejected the Énergie Saguenay LNG proposal,1 based on the results of a two-year public environmental impact assessment released a few months earlier. The assessment panel recommended against the project due to concerns that increased greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, threats to marine mammals including endangered beluga whales, and adverse social impacts on local First Nations outweighed any potential benefits. The spur pipeline was subject to a separate federal environmental assessment process that became moot after the province turned down the LNG facility.

In February 2022, the federal minister of environment also denied approval for the proposed LNG facility.2 That decision was based on Ottawa’s parallel environmental impact assessment (EIA), which had recommended against the project in November 2021. The federal environment minister and the federal EIA flagged similar environmental and social concerns to those expressed by the Quebec authorities.

Without these necessary provincial and federal approvals, the project is effectively dead. But the Ruby River saga is not over.

In February 2023, the foreign investor challenged Canada under the “legacy” investment protection provisions of the Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA) and NAFTA Chapter 11.

In July 2020, NAFTA was superseded by the renegotiated CUSMA. While CUSMA eliminated ISDS between Canada and the U.S., it allowed foreign investors to continue to bring claims under the oldNAFTA investment chapter rules for three years after CUSMA’s entry into force (i.e., until June 30, 2023).

In its February 2023 request for arbitration, Ruby River objects to the allegedly “fundamentally arbitrary, procedurally grossly unjust, expropriatory, and discriminatory treatment” the proposed Saguenay LNG facility received from both the Quebec and Canadian governments.3 It claims that federal and provincial government measures violated various NAFTA investment protections. The firm initially sought compensation of “no less than” $20 billion USD (about $27 billion CAD4). This was the largest amount ever claimed by an investor under the ISDS provisions of NAFTA and ranked among the highest known investor-state claims currently underway (see Table 1).

On November 21, 2023, for legal reasons related to the convention governing the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID Convention), Ruby River adjusted its $20 billion USD claim downward to “at least” $1.004 billion USD. The investor based this revised figure on the hypothetical “going concern” value of the proposed project and any incurred costs up to the final date of the award of the tribunal. The $1.004 billion USD is simply notional, calculated by an expert consultant based on a “proxy date” of September 30, 2023.

Since the proceedings of the tribunal are likely to continue for several more years,5 this estimate is for illustrative purposes only.6 If the claimants were to win, and their preferred method for calculating the award were accepted by the tribunal, the amount of the award would certainly be much higher. Since the company-commissioned expert’s valuation report is confidential, it is hard to know by how much, but we can estimate it would be several billions of dollars.

In June 2023, a tribunal was constituted to hear the case under the auspices of the International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID), an international arbitration body associated with the World Bank and headquartered in Washington, D.C. ISDS cases are heard by tribunals of three members: one chosen by the investor, one chosen by the challenged government, and a chair who is usually selected by mutual agreement.7 In the Ruby River case, the chair is Carole Malinvaud, a Paris-based lawyer and commercial arbitrator. The tribunal’s decision will be legally binding on the Canadian government and is not subject to appeal or review by the Quebec or Canadian courts.

How Ruby River’s plan would negate climate action

Governments around the world, including Canada and Quebec, have committed to drastically reduce GHG emissions, including carbon dioxide and methane, in an effort to forestall global warming. Unfortunately, so far, Canadian efforts have fallen far short of meeting these pledges.8

A September 2023 report by the International Energy Agency warned that to achieve net-zero emissions by mid-century, fossil fuel demand must fall by 23 per cent by the end of this decade, and by 76 per cent by 2050.9 Clearly, to have any hope of meeting the internationally agreed goal of limiting average global temperature increases from climate change to 1.5 degrees Celsius, fossil fuel production and associated infrastructure must be wound down.

This will mean wrenching changes for the Canadian economy. Yet with increasing wildfires, extreme weather, rises in ocean temperature, and other cascading climate-related calamities, the rising costs of climate inaction are becoming all too clear.

Sadly, it is rare for Canadian governments to take the hard decisions consistent with their ambitious GHG reduction pledges. But when elected officials find the courage to act decisively, by curtailing fossil fuel projects, it is absurd for prospective investors, such as Ruby River, to feign shock and indignation.

The Énergie Saguenay LNG project would have locked in significantly increased GHG emissions for decades to come.10 The Quebec and Canadian government decisions to reject the megaproject were hailed by a broad grouping of environmental advocates, Indigenous groups, and concerned citizens urging meaningful climate action. This outcome should have been foreseen by any prudent investor. Indeed, Berkshire Hathaway, a major backer of the project, withdrew a $3 billion USD offer of financing in 2020.11

The Énergie Saguenay project would clearly have been a serious setback for efforts to reduce Canadian and global GHG emissions. A study commissioned by the industry estimates the project would create 7.8 million tonnes of GHG emissions per year.12 By the industry’s own calculations, then, this single project would have resulted in an increase equivalent to 1.43 per cent of Canada’s total GHG emissions in 2021.

Independent experts, however, noted that these industry-sanctioned estimates ignore downstream emissions—when the natural gas is consumed—as well as upstream fugitive emissions of highly polluting methane in the fracking and transportation of the gas.13 These scientists estimated that, even after excluding the effects of fugitive emissions, the downstream impacts would add at least 30 million tonnes of GHGs per year, amounting to a 6.9 per cent increase over Canada’s current annual emissions.

Despite these inconvenient facts, the investor’s NAFTA complaint doggedly insists that the LNG project would be “carbon-neutral” and have “net zero” impact on Quebec’s GHG emissions. The company has claimed that 100 per cent of the project’s direct GHG emissions would be offset by measures “ensuring that as much CO2 is sequestered as the quantity produced by operations, each year.”14

These assertions of carbon neutrality rest on a series of highly questionable assumptions that were systematically discredited during the provincial and federal environmental assessment processes and accompanying public and scientific debate.

First, the net zero claim assumes that all the gas the facility exports would supplant the burning of dirtier fossil fuels. But, as independent climate experts observed, “GNL Quebec would have no control over the end use of this gas, and there is no evidence that its use would replace coal or oil fuel. It is just as likely that this gas could replace renewable energy sources, which would only increase the world’s continued reliance on fossil fuels and slow the desperately needed development of alternative energy technologies.”15

The decarbonization claims also assume that the facility would be largely powered by hydroelectricity, a low-carbon form of renewable energy. Yet the investor never secured a firm commitment from the Quebec government or Hydro-Québec, the government-owned provincial energy utility, to supply that power. Hydro-Québec is already facing a supply shortfall as domestic and regional demand for its hydroelectricity has grown.16

Moreover, that limited supply of publicly owned hydropower, which meets 50 per cent of Quebec’s total energy demands, could be put to far more climate-friendly uses. Electrifying the region’s heating, cooling, and transportation systems, thereby reducing the province’s GHG emissions, would be far preferable to enabling a fossil fuel megaproject locking in future GHG emissions.17

The net-zero assumptions also depend on flawed measurements of emissions. As noted, they ignore the issue of fugitive methane emissions in the fracking and transport of natural gas procured from Western Canada, another unavoidable factor. Methane is a potent greenhouse gas: over a 20-year period, it is 80 times worse than CO2 at trapping heat in the atmosphere.18

When all other arguments fail, the project’s proponents pledge to purchase carbon credits to offset the project’s unavoidable emissions. This loosely regulated market in “permits to pollute” is controversial, and plagued by problems with faulty measurement and fraudulent credits.19

Finally, the investor’s argument that LNG is a “transitional fuel” on the path to a fossil-fuel-free future has been thoroughly debunked.20 Even the International Energy Agency, which promotes the idea that existing natural gas capacity could play a role in the energy transition, seriously questions the need for constructing new LNG facilities that would lock in GHG emission for decades.

A NAFTA investment tribunal is not the appropriate venue to assess the validity of the company’s contentious claims about the project’s carbon neutrality. The relevant arguments and scientific evidence have already been examined exhaustively, in an inclusive public forum, during the federal and provincial EIA reviews. Both independent reviews came to the same conclusion that the project would significantly increase GHG emissions. For this, and other compelling reasons, governments ultimately denied approval.

A tribunal comprised of trade lawyers deliberating in private is not fit to second-guess such considered, participatory and lawful determinations. Tragically, however, it has now been empowered to do so.

In sharp contrast to the mandates of the EIA panels, the investment tribunal will not base its final decision on what is best for the local community or global environment. Its mandate is to judge whether the investor’s treaty-based rights have been violated. In doing so, the panel will be strictly guided by its interpretation of NAFTA’s expansive investment protections.

Democracy under challenge

Based on the strength and integrity of the Quebec and federal EIA processes, you might assume that Ruby River’s NAFTA case is destined to fail. Unfortunately, we’ve been here before: NAFTA has already been used to successfully challenge the results of a Canadian environmental impact assessment, this one for a planned quarry on the Bay of Fundy.

In 2007, after three years of extensive study and public consultation involving all interested parties, a joint federal-provincial environmental assessment panel recommended against a proposed quarry and related marine terminal due to their negative environmental and socioeconomic effects. The governments of Nova Scotia and Canada accepted that recommendation, denying approval for the controversial project.

Bypassing the Canadian courts, the U.S. investor in the project, Bilcon, took its objections directly to NAFTA investor–state dispute settlement. In a two-to-one decision in March 2015, the tribunal ruled that the conduct of the environmental impact assessment panel, and the subsequent decisions to deny approval for the project, violated the company’s NAFTA guarantees to a minimum standard of treatment and national treatment. In January 2019, the tribunal awarded the claimant $7 million USD plus interest accruing from October 2007.

The dissenting tribunal member strongly condemned the majority’s ruling as a "significant intrusion into domestic jurisdiction” that “will create a chill on the operation of environmental review panels," and “a remarkable step backwards” for environmental protection.21

In May 2018, a Federal Court judge reviewing the Bilcon ruling concurred, stating: “I accept that the majority’s Award raises significant policy concerns. These include its effect on the ability of NAFTA Parties to regulate environmental matters within their jurisdiction, the ability of NAFTA tribunals to properly assess whether foreign investors have been treated fairly under domestic environmental assessment processes, and the potential ‘chill’ in the environmental assessment process that could result from the majority’s decision.”

Despite this clear disapproval of the tribunal majority’s reasoning, the Court ruled it lacked a legal basis to set aside the tribunal’s decision, as requested by the federal government.22

There are strong overlaps between the investors’ arguments in the two disputes. In the Ruby River case, the investor’s primary grievance appears to be that the Quebec government “led them on,” after government officials initially encouraged them to seek approval and public financing for the LNG project, only to have cabinet subsequently turn it down for “political reasons.”

In particular, the investor’s request for arbitration vehemently objects to the Quebec government’s supposedly “sudden” emphasis on the project’s contribution to global GHG emissions and its impacts on the green energy transition.23

On the day of the public release of the report of the Bureau d’audiences publiques sur l’environnement (BAPE), the Quebec environment minster announced that cabinet would only approve the project if it met three conditions: it made a “positive net contribution” to global GHG emissions reductions, it “promoted energy transition,” and it achieved “social acceptability.”24

According to Ruby River, the government “moved the goalposts” by applying these “core criteria,” hence violating the investor’s “legitimate expectations.” In its request for arbitration, the investor denounces these terms as “newly invented and imposed.”25

This totally misrepresents the situation. In fact, the project’s potential impacts on global GHG emissions and the transition to green energy had been discussed extensively during the public hearings and were reflected in the BAPE report, to which the minister was reacting.

At various points in its report, the BAPE commission of inquiry raised concerns about the potential negative impacts of the project on global GHG emissions and the transition to low-carbon energy. To highlight only a few examples, the report notes the following (translated from French):

International Energy Agency scenarios for GHG reductions in line with the achievement of the Paris Agreement show “the demand for natural gas is decreasing in Europe when the Énergie Saguenay project begins its operational phase, and remains sustained in Asia until 2040, before decreasing in several Asian countries.” Furthermore, in these scenarios, “existing liquefaction terminals or those currently under construction would be sufficient to meet demand until 2030 and could be in excess of 2040” (p. 110).

Establishing new LNG exchange infrastructure “could act as a brake on the energy transition in the markets targeted by the Énergie Saguenay project, since joining this supply chain could have the effect of locking in the long-term energy choices of customer countries and, consequently, the GHG emissions associated with the combustion of the natural gas that would be delivered there” (p. 114)

To justify and finance the LNG project, “the initiator would need to obtain long-term commitments from future customers, which would lock in their energy choices and, in doing so, could delay their transition to a low-carbon economy” (p. 114).

The supply of natural gas for the Énergie Saguenay project “would contribute to the maintenance or growth of the oil and gas sector in Western Canada, whereas, according to the International Energy Agency, significant amounts of hydrocarbon reserves would have to remain undeveloped to achieve the central objective of the Paris Agreement” (p. 114).

A key issue in the arbitration will be whether the tribunal accepts the investor’s allegation that this was a sudden change, a volte face, that dashed the investor’s “legitimate expectations.”

For all intents and purposes, the decision was a legitimate exercise of cabinet discretion, in response to an open and transparent public process. The Quebec government’s decision was lawful, within its authority, consistent with the conclusions of the EIA, welcomed by many citizens, and, while not a foregone conclusion, was certainly not a surprise.

The investor also alleges that they suffered discriminatory treatment, because other investors that were supposedly “in like circumstances” had their investment projects approved. Going back as far as 2015, the investor’s complaint cites the Quebec government’s approval of several (much smaller) industrial projects involving marine facilities along the St. Lawrence River as proof that it was being discriminated against based on its nationality. This strained argument equates instances where different projects are treated differently for any reason to situations in which an investor faces outright discrimination based on their nationality.

Governments often treat investors differently for perfectly legitimate reasons. Furthermore, in a democratic system, standards regarding acceptable environmental impacts and social benefits evolve, as has been the case during the rapidly accelerating climate crisis. Worryingly, however, a similar set of pro-investor arguments were accepted as valid by the tribunal in the Bilcon NAFTA case.26

The investor’s grievances involve a wilful misunderstanding of EIAs and democratic decision-making. EIAs are independent processes, conducted at arm’s length from government—and, importantly, with no predetermined outcome. Impact assessment bodies are mandated to review all the evidence, assess and verify the project proponent’s claims, and seek and consider the views of other stakeholders, local communities, and the public at large.

The proposed LNG project was, according to the proponents themselves, the largest industrial project in Quebec history. The EIA also attracted high public interest and “garnered the greatest response of any BAPE review, with more than 2,500 briefs presented.”27

The input of local First Nations also played an important role in the decision to deny approval. Canadian EIA processes still fall well short of the goal of “free, prior and informed consent” enshrined in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).28 But federal law does require full participation in EIAs by affected First Nations and to have their “traditional knowledge and treaty rights respected and prioritized.”29

The Innu First Nations, on whose unceded, ancestral lands the project would be built, publicly opposed the project.30 Their concerns included the negative effects of increased marine traffic on Beluga whales (a locally endangered species of great cultural significance to their peoples), negative environmental and aesthetic impacts on the Saguenay Fjord and recreational tourism, and the environmental harm from increased GHG emissions in the context of climate change.31

Innu leaders concluded that “this project is detrimental to future generations and is clearly inconsistent with a healthy vision of the future as well as with the global and societal challenges of the coming decades.”32

Naturally, the project proponents were disappointed by the final decisions of the federal and provincial governments. But this was a risk they knowingly accepted.

Even the fact that they may have been advised and encouraged by public officials at various points is unsurprising, even trivial. The mandate of the EIA panel is vastly different from that of economic development officials—and, crucially, the process is independent of government and the bureaucracy.

An environmental impact assessment panel’s task is to weigh the potential benefits of a project, alongside environmental, social, and other risks and concerns. They are also obligated to encourage and consider arguments, evidence, and concerns not only from the proponents, but also a wide range of officials, independent experts, indigenous peoples, local communities and the general public.

Both the Quebec and federal assessments were carried out consistently with provincial and federal law, regulations and practice. The final government decisions to follow the recommendations and deny approval were made, on rational grounds, according to law.

Nonetheless, the investor’s request for arbitration describes these public processes and subsequent government decisions as “manifestly arbitrary and discriminatory,” “grossly unfair,” “abusive,” “prejudicial,” “fundamentally unjust,” and based on “political expediency unrelated to any legitimate public purpose.”33 Such inflammatory terms unwittingly illustrate how unhinged the sphere of investment arbitration has become from the complexities of democratic decision-making in an era of rapid and dangerous climate change.

Risks to public finances

The initial amount of compensation sought by Ruby River, “no less than” $20 billion USD, was staggering—the most ever requested by an investor under NAFTA investor-state dispute settlement. Yet even the revised amount now sought by the investor could be several billions of dollars. If they win, it would easily be the largest NAFTA award to date.

Though it is outrageous to think Canada may have to compensate Ruby River for its alleged lost future profits, it would be a mistake to discount the investor’s demand as far-fetched. While investors who win ISDS disputes typically get less compensation than they ask for, tribunal awards can be large (in the hundreds of millions or billions of dollars).34 This trend has led some experts and governments to conclude that ISDS damages are “out of control.”35

As described above, Ruby River’s inflated demands are based on the investor’s speculative estimate of the fair market value of the LNG project at the date of the tribunal’s final decision. It is many times the costs actually incurred in seeking project approval ($120 million USD by the investor’s estimate).36 If Ruby River were to win the compensation it seeks, it could make the investor-state litigation a more profitable venture than proceeding with the Énergie Saguenay project itself, with all its attendant risks.

Even setting aside the climate costs and regulatory risks associated with such a major fossil fuel project, the claimant’s rose-tinted profit projections ignore the fundamental business uncertainties stemming from operational issues and market volatility that have beset similar LNG projects.

For example, in March 2023, the Spanish company Repsol abandoned its proposal for a LNG terminal in Saint John, New Brunswick despite enjoying enthusiastic support from the provincial government. The company concluded that the project was uneconomical because the cost of shipping Western gas to the Atlantic coast for export to Europe was too high.37

Taking a case to investment arbitration is expensive. But this will not be a burden for Ruby River because its expenses are being financed by a third party.38 Third-party financing occurs where financial speculators (e.g., a hedge fund) cover the legal costs of an ISDS claimant in return for a share of the award if the claim succeeds. This form of profiteering, which promotes itself as a new type of “uncorrelated” investment asset, is a burgeoning industry. It is also a growing public policy concern because it encourages and sustains ISDS cases that might not otherwise be viable.39

The international law firm representing Ruby River, Steptoe and Johnson, is one of the top 125 law firms in the world by revenue and has a thriving investment arbitration practice. Notably, the lead counsel in this case, Christophe Bondy, is a former senior Canadian public servant who, during his career as a government lawyer, defended the federal government in high-profile NAFTA ISDS cases. Bondy was also senior counsel to Canada in the negotiation of the Canada–European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA), “with particular emphasis on services and investment chapters.”40

In the insular world of investment arbitration, it is not unusual for senior government lawyers to migrate to the private sector, where they frequently represent claimants suing their former government employer.41 This revolving door, and divided loyalties, may help explain the perplexing decision by Canada not to weigh in on a key jurisdictional issue in the Keystone XL NAFTA case, where a favorable decision could have greatly strengthened Canada’s hand in the similar Ruby River dispute.

As discussed, CUSMA allows foreign investors to continue to bring “legacy” ISDS claims under the old NAFTA investment chapter rules for three years after CUSMA’s entry into force—until June 30, 2023. In 2021, TC Energy controversially invoked the legacy provision in CUSMA to re-launch its $15 billion USD NAFTA suit against the U.S. related to President Biden’s January 2021 cancellation of the Keystone XL pipeline. Significantly, the Alberta Petroleum Marketing Commission, an Alberta government entity, is also pursuing a multi-billion-dollar NAFTA legacy claim against the U.S. over the cancellation of Keystone XL.42

As part of its defence in this second Keystone case and the parallel Alberta claim, the U.S. is arguing that the legacy provisions in CUSMA apply only to ISDS claims related to measures taken before July 1, 2020, when NAFTA was terminated.43

If the U.S. position prevailed, the Keystone XL claim would be disallowed on jurisdictional grounds. It would mean that other legacy claims related to Canadian and Mexican government measures taken after July 1, 2020 might also be disqualified. This could include the Ruby River claim, which pertains mainly to actions that occurred after 2020, notably the decisions by the Quebec and federal governments to reject the project, which were taken in July 2021 and February 2022, respectively.

NAFTA rules allow non-disputing parties to make their views on interpretive matters known to ISDS tribunals. Mexico intervened in the Keystone case at the jurisdictional stage to strongly support the U.S. position.44

Canada, however, chose to remain silent. If all three NAFTA parties had strongly supported the view that the legacy provisions were retrospective, it would certainly have strengthened the argument that both the Keystone XL and Ruby River challenges were barred.45

This was an irresponsible decision, both from the standpoint of the Canadian taxpayer and that of climate justice. Canadian lawyers could, and should, have tried to mitigate the risk of a multi-billion-dollar settlement. Instead, out of fear of alienating the Alberta government and TC Energy, the Canadian legal team requested a suspension of the Ruby River case until other tribunals had ruled on the validity of the U.S. and Mexican interpretation of the legacy provisions.

Unsurprisingly, the tribunal rejected Canada’s clumsy request. In its decision, the tribunal noted acidly that Canada had neither intervened to support the U.S. view in the Keystone XL case nor raised the jurisdictional issue directly in its own defence.46 Left out in the cold, the Quebec government was compelled to seek leave from the tribunal to raise the key jurisdictional issue through an amicus brief.47

Given the high financial and environmental stakes in this case, Canada ought to have pursued every available legal defence. It might also have respected the newly elected Biden administration’s decision to cancel the Keystone XL pipeline. Instead, through its inaction, it chose to side with TC Energy and the Alberta government—the key backers of the doomed and environmentally harmful pipeline project. Given this mishandling of Canada’s legal defence, it would be reasonable for the Quebec government to insist that Ottawa assume full financial responsibility for any eventual payout if Ruby River wins its case.

Impeding climate action

A July 2023 United Nations report concluded that ISDS poses a “catastrophic” threat to climate mitigation and adaptation efforts and the achievement of human rights.48 The Ruby River case was one of the major fossil fuel arbitrations highlighted in that damning report.

This attention is warranted. The case typifies most of the elements that led the UN report to warn that ISDS is such a serious threat to climate action.

At several billion USD, the damages sought are among the highest of all known NAFTA legacy claims and the largest ISDS claim ever filed against Canada.

The risk of incurring huge payouts for turning down fossil fuel projects casts a pall over bold climate action, emphasising the notorious “chilling effect” that the presence of ISDS can put on governments.49

The Ruby River case also illustrates the “revolving door”50 that characterises the insular, and highly lucrative, arbitration industry— with the investor represented by a former Canadian public servant who has shifted allegiance to a prominent international law firm.

The penchant for secrecy was apparent when, in one of its first decisions, the tribunal ruled that the hearings will be held behind closed doors. Presumably the investor refused to consent to open hearings, since Canada typically supports transparency in ISDS proceedings.51

The case highlights how ISDS not only elevates investor expectations to the status of internationally protected legal rights, but that it does so in a way that excludes all other interests, including those of Indigenous Peoples, affected communities, and even other business interests.

Perhaps the most insidious element is the casual contempt for democratic decision-making expressed by the investor and inherent to the investor-state dispute settlement regime. At the media conference announcing it had denied permission to the Saguenay project, the provincial government was represented by two cabinet ministers—the environment minister who had been critical of the project and the economic development minister who had backed it strongly. This show of unity conveyed that the government, and indeed the province, had, after careful deliberation and open debate, come to a decision that should now be accepted by all going forward.

This democratic sensibility is twisted, in the project proponent’s request for NAFTA arbitration, into a betrayal, an “unforeseen and fatal volte-face,” a “seriously compromised and biased” decision-making process, resulting in a “cavalier disregard” of the investor’s “legitimate expectations.”52 Such posturing would appropriately get short shrift in the domestic legal system,53 but it is a staple of the investor-state arbitration system. In that privileged domain, jilted foreign investors routinely extract financial retribution for even-handed and lawful government decisions.

The Ruby River investor-state challenge, and cases like it, erode the key hope for decisive action to avert catastrophic climate change. That is, that citizen movements, Indigenous Peoples, and local communities can join together to press elected officials to block new fossil fuel projects and phase out existing ones. This is exactly how the Énergie Saguenay project was stopped. This remarkable, public-spirited environmental victory should be celebrated and emulated, not penalized.

Mobilizing to transform the world’s energy systems is already a monumental, existential challenge. Climate adaptation and mitigation will involve huge demands on public finances to ensure affected peoples, workers, and vulnerable communities are supported in a just transition. In such a context, the hanging threat of massive, punitive fines levied through a parallel and unaccountable quasi-legal system and paid exclusively to foreign investors is, as the UN report concludes, unconscionable.

At least Ruby River’s lawsuit will be the last claim of its kind against Canada under NAFTA’s now-expired ISDS system. The Canadian government made a principled decision in the CUSMA negotiations to eliminate ISDS from the new treaty (at least for U.S. investors)—thereby protecting Canada’s ability to set environmental and other key public policies without threat of retaliation. Canadian firms like TC Energy will no longer be able to menace the U.S. either.

If only the government had chosen to extend that wise decision to its relations with the rest of the world. Instead, Canada remains entangled in dozens of investment treaties and free trade agreements containing ISDS and is negotiating a half-dozen more with countries such as Ukraine, Indonesia, India, the ASEAN bloc of nations, and Taiwan. The United Kingdom’s accession to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership virtually ensures that Canada will be hit by future ISDS claims related to fossil fuel projects and climate measures.

Perhaps the only silver lining to the audacious, anti-democratic Ruby River complaint is that it might prove a catalyst for Canada to finally erase ISDS from all its treaty commitments and to support international efforts to exit and dismantle the investor-state system.54