Executive summary

Don’t Wait for the State: A blueprint for grassroots climate transitions in Canada offers a framework for communities to organize around the idea of an inclusive and productive transition to a cleaner local economy.

Every community across Canada depends on fossil fuels for transportation, heating, food production and other vital needs. Confronting the climate emergency by tackling our society’s reliance on fossil fuels is an urgent necessity for each one of us. Nonetheless, climate action pursued without a bold and inclusive transition plan risks widening already dangerous levels of inequality, further polarizing politics, and deepening social and economic hardship for many. This is especially the reality for Indigenous, racialized and other historically marginalized people, who have contributed the least to the problem, have the least capacity to adapt, and yet are experiencing the most severe impacts of a changing climate.

Unfortunately, while climate breakdown accelerates and theatrical political debates over transition fill the airwaves, communities are still waiting for action at the local level. This report is aimed at local organizers and community leaders who are tired of waiting and ready to act.

The paper begins by outlining a vision for grassroots climate organizing that takes as its inspiration the idea of a “just transition,” which is grounded in the labour movement’s fight to ensure workers are prioritized in the transition away from fossil fuel production. Organizing for climate justice and local power can build on and reinforce worker-focused just transition initiatives while advancing a broader set of community priorities.

We then turn to a variety of case studies of community organizing in the context of climate transitions. Our examples, from Australia to Mexico to Ireland and beyond, highlight the importance of grassroots movements for instigating, informing and shaping climate action in their communities. Our cases are not all success stories, but each one offers lessons for organizers elsewhere.

From these case studies we draw 12 best practices for community climate organizing:

- Start building community power early in the transition.

- Clarify the bounds of the community in question.

- Reckon with historical injustices and past unsuccessful transition efforts.

- Promote local community knowledge.

- Employ democratic organizing processes.

- Build broad coalitions of allies.

- Develop alternative data sources.

- Build movement capacity and confidence.

- Map relevant power structures.

- Envision a better future together.

- Move from social dialogue to practical action.

- Emphasize public ownership and control over solutions.

Based on these best practices, the report presents a “5D” framework for grassroots climate transition organizing. Every community is different and each will require a unique approach, but, in general, we recommend organizers consider these five steps as a starting point:

- Define the community that is undergoing transition.

- Design inclusive and iterative processes for organizing the community.

- Dream up a better future together.

- Determine the constraints holding back effective action.

- Deliver real alternatives for members of the community.

Governments at all levels can, and should, be doing more to ensure a fair and just transition to a clean economy. Ultimately, no large-scale climate transition will succeed without government coordination and public investment. Yet, where governments are dragging their feet, communities need not wait for the state to lead. Through grassroots organizing, communities can define, design, dream, determine and deliver a better future for all.

Introduction

Achieving a productive and inclusive transition to a sustainable economy is a goal shared by communities across Canada and around the world. Not only do we urgently need to get fossil fuels out of the economy, but we also need to ensure people are not left behind by the shift. Overcoming our dependence on coal, oil and gas without an inclusive and expansive transition plan risks harming and displacing people who produce and consume those fuels—especially already marginalized communities—when we could be taking this opportunity to redress historical inequities and build a more prosperous future for all.

The concept of a “just transition” has emerged as one solution to the problem. Just transition, which refers to a framework for fairly distributing the costs and benefits of climate policies for workers, originated in the organized labour movement and has since been adopted by environmentalists, social justice advocates and governments. In Canada, multiple levels of government have supported a just transition out of the coal power sector over the past decade. Moving forward, the federal government has introduced a Sustainable Jobs Plan and pledged to introduce national legislation to support workers in other sectors of the economy as Canada pursues its emission-reduction targets.

While promising, Canadian just transition initiatives, to date, have had mixed success.1 Government policies have been relatively unambitious and limited in scope to a small subset of affected workers.2 They have reacted to the social dislocations caused by climate policies rather than being proactive in building up socially just and sustainable economic alternatives.3 Furthermore, the kinds of high-level transition policies implemented by Canadian governments have tended to ignore or downplay local and regional needs that may differ from national or provincial agendas.

Many people in fossil fuel-dependent communities wonder about their future well-being and economic security. Even for communities that are not directly involved in the production of fossil fuels, the disruption and cost associated with climate transitions—the phasing out of everything from gasoline-powered cars to gas heat in homes—is sowing fear and resistance. As the climate crisis intensifies and the global transition to a lower-carbon economy unfolds, every community across Canada will need to reckon with these challenges.

This paper offers a blueprint for community organizers and concerned citizens seeking to tackle the question: How do we navigate a climate transition in our communities in the absence of proactive government action?4 There is no escaping the importance of government policy for achieving large-scale energy transitions and we do not propose that communities give up on the state. Indeed, communities must inevitably engage with governments to make their vision a reality. Communities can also move in tandem with the worker movements that are pushing for a just transition, which remain integral allies in the fight for fairness, justice and economic equality. Grassroots climate transition planning can kickstart local action where governments have failed to proactively address the specific transition needs of individual communities and where the people at stake go beyond energy workers.

The paper begins with a discussion of the inequitable impacts of the climate crisis, a review of the just transition concept, and the clarification of key terms. We consider how the principles and lessons from the worker-focused just transition movement can inspire new movements to organize around climate transitions. We then turn to a series of case studies where community-level transition planning, inspired by the idea of a just transition, has already been pursued. We review existing initiatives that are intended to support community organizing. We then draw a list of best practices for Canadian communities hoping to organize around local climate transitions. In the final section, we present our proposed “5D” framework for achieving a grassroots climate transition: (1) defining community, (2) designing processes, (3) dreaming up a greener future, (4) determining constraints and (5) delivering alternatives.

Our goal is to empower communities across Canada—defined broadly to include communities organized by place, culture or other shared values—to map out their own future in a world undergoing rapid changes that are driven by the climate crisis. Community-level transition roadmaps can clarify goals, mobilize support for climate action, feed into the policy-making process, and ultimately smooth the transition to a cleaner, more inclusive future for all.

The climate crisis and a just transition

The climate crisis is no longer banging on the door—it’s inside the house. Uncontrolled wildfires, extreme storms and devastating floods that were once occasional concerns have become annual threats in many parts of Canada. The direct costs of climate-related damages hit $20 billion in 2021 and are on track to reach $25 billion per year by 2025 and $100 billion per year by 2050, with the costs falling disproportionately on already vulnerable populations.5

This grim forecast merely reinforces the warnings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which has repeatedly stated that climate change is already causing “widespread adverse impacts and related losses and damages to nature and people” that will only get worse in the coming decades.6 Slowing global warming will require “rapid, far-reaching and unprecedented changes in all aspects of society,” including “a substantial reduction in overall fossil fuel use” that leaves “a substantial amount of fossil fuels unburned and could strand considerable fossil fuel infrastructure.”7 Even historic oil boosters like the International Energy Agency have acknowledged that addressing climate change requires “a huge decline in the use of fossil fuels” and that there can be “no new oil and gas fields… and no new coal mines” moving forward in order to meet global climate targets.8

While governments around the world have been slow to respond to these warnings, more and more countries, including Canada, have committed to net-zero emission targets, which imply a near-total phase-out of fossil fuels by mid-century.9 Based on current policies, Canada is not on track to meet these commitments, in part due to a continued commitment to oil and gas extraction for export.10 Nevertheless, it is clear that the global energy system is already changing and may well be transformed in the coming decades. Canadian communities will be forced to respond, whether our governments lead the climate charge or not. When we talk about “climate transitions” in this paper, we are referring to the raft of social and economic shifts that are both necessary and inevitable to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

Putting aside the obvious benefits of moving away from fossil fuels, such as significant improvements in human health from reduced pollution,11 phasing out coal, oil and gas negatively impacts people in two ways. First, winding down the fossil fuel industry directly impacts the workers and communities who depend on coal, oil and gas production for their livelihood. In Canada, while fossil fuel workers only account for less than one per cent of the total workforce, that still amounts to more than 150,000 workers and dozens of communities, mainly in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador.12 As a major export industry, the fossil fuel sector also underpins many other industries and jobs across the country. In the absence of a green industrial policy to scale up alternative industries, cutting production will have far-reaching economic effects.13 Second, taking fossil fuels out of the economy comes with costs for energy users who depend on oil for their vehicles, coal for their electricity and gas to heat their homes. In both cases, an unmanaged transition risks creating significant economic hardship and associated social problems that are reminiscent of so many previous resource busts in Canada.14

The costs of moving away from coal, oil and gas are not evenly shared. In the same way that poor, racialized, Indigenous and other marginalized communities have suffered disproportionately from environmental degradation and hazards, marginalized people often experience the costs of transition more acutely.15 For example, lower-income households typically spend a greater share of their income on energy, so if clean energy policies increase energy costs, that may increase poverty levels.16 Many rural and remote Indigenous communities are especially vulnerable because of a dependence on diesel generators.17 In the absence of viable alternatives, cutting the supply and/or increasing the cost of emissions-intensive diesel will harm these communities. Even among fossil fuel workers, it is the highest-paid professionals, such as engineers, who will have the easiest time transitioning to new industries compared to, for example, labourers and rig operators in oil fields—let alone the migrant workers who serve them lunch and do their laundry in work camps.

Conversely, many of the benefits of transitioning to a lower-carbon economy are concentrated in the hands of the already well-to-do. Government incentives for zero-emission vehicles and building retrofits, for example, subsidize the consumption of high-income households without making low-emission transit or energy efficiency more accessible to low-income households.18 On the employment side, white, Canadian-born men who generally enjoy high income and other privileges dominate many of the industries poised for growth in the clean economy, such as green energy and the building trades.19 Policies to scale up a sustainable economy, in the absence of efforts to diversify the workforce, will merely reinforce existing inequities in the labour market.

Re-radicalizing just transition

The concept of a “just transition” has emerged as the progressive alternative to a chaotic, market-led shift in the energy system. The term originated in the organized labour movement specifically to protect unionized workers displaced due to environmental policies. Tony Mazzocchi, the U.S. labour organizer who is widely credited with popularizing the idea, first made the case in 1993 for “an ambitious, imaginative program of support and re-education… [to] guarantee full wages and benefits to employees who lose their jobs due to environmental regulations.”20 The term “just transition” itself appears to have been coined in Canada by the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers Union in 1996.21

To the labour movement, just transition includes policies such as income supports and retraining programs to ensure workers’ livelihoods are protected as they transition to new jobs in other industries. In 2015, the International Labour Organization (ILO) encapsulated the movement’s priorities in its Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all, which emphasized social dialogue, decent work and labour rights.22 The labour movement has been key to winning recognition for the principles of a just transition in international law, including in the Paris Agreement.

More recently, the concept has been interpreted by a range of progressive actors, including in environmental and social justice movements, to capture a broader agenda of societal change in response to the climate emergency. Under this more expansive definition, just transition includes foregrounding the voices and demands of historically marginalized communities, expansive universal public services, an emphasis on the low-carbon care economy, public spending on economic alternatives, and a green industrial strategy to fast track new industries and make good on a green jobs guarantee. Advocates move beyond instrumental employment concerns to embrace issues of energy democracy and public power.23 While there is overlap with the ILO priorities, groups like the Climate Justice Alliance emphasize self-determination, redistribution, and economic transformation in their definition of a just transition.24 Some Indigenous communities have also adopted just transition language to centre issues of reconciliation and historical justice in the climate discourse.25

As just transition has moved from the advocacy space into the policy space, it has taken on new meanings. Governments that employ the term have occasionally used it to rebrand traditional and inadequate workforce transition programs, which has led to significant worker distrust of the term—from coal workers in Appalachia and New Brunswick to oil workers in Alberta to forestry workers in British Columbia.26 The U.S.-based Just Transition Listening Project, which engages with communities that are undergoing or have undergone economic transitions, has found that these communities are, in general, deeply skeptical of just transition policies.27 Where just transition policies are more genuine, critics argue that the term nevertheless risks being used as a “disciplining device that steers local activists towards approaches that are compatible with government policy directions.”28 For its part, the Canadian government has watered down the concept to mean a focus on community consultations and “inclusive economic opportunities” in place of the more radical concepts of self-determination and direct job creation.29 Many Canadian workers and communities have understandably come to view just transition as an exercise in government greenwashing.30 That may explain, at least in part, the federal government’s recent preference for the phrase “sustainable jobs,” which has fewer pre-existing connotations.

The Just Transition Research Collaborative, a group of international academics and experts, has attempted to map these various understandings of a just transition along two axes. First, on a spectrum from “exclusive” (i.e., benefiting a specific group) to “inclusive” (i.e., benefiting society as a whole). Second, on a spectrum from “no harm done” (i.e., preserving the status quo) to “new vision” (i.e., transforming the existing political and economic system).31 They find that most just transition advocates—including labour unions—define the term in more-or-less inclusive and transformative terms. However, where governments have pursued “just transition” policies, they have generally been exclusive in scope and more protective of the status quo. There is both a need and an opportunity, then, to re-radicalize the political narrative around a just transition to achieve its transformative potential. Given the “failure of elected officials to deliver just transition policies,” as the Just Transition Listening Project concludes, it falls to organizers to recapture the promise of a just transition and advance a concrete, progressive alternative.32

What does that look like in practice? For the purposes of this paper, we recognize two parallel and complementary trajectories: (1) labour organizing toward a just transition, which is fundamentally focused on the dignity and well-being of affected workers, especially in the energy industry, and (2) the broader array of climate justice movements that are inspired by the idea of a just transition (whether or not they use the exact term) and are fighting for societal transformation, prioritizing the demands and voices of Indigenous and other historically marginalized communities, and connecting the dots among many connected crises and ambitious solutions. The two tracks are grounded in the same principles of justice and social power, compounding their effectiveness when coalitions are pulling in the same direction.33

Nevertheless, there are practical distinctions. The ongoing dialogue between unions, governments and industry that constitutes the just transition (or “sustainable jobs”) policy space today is generally focused on fossil fuel workers in fossil fuel communities. When we use the term “just transition”, we are referring to these sorts of worker-focused efforts. Climate justice organizing, on the other hand, considers a more diverse set of individuals and communities who are impacted by the climate transition in different ways. We refer to this umbrella of initiatives as “community-led climate transitions” or “grassroots climate organizing”.

This paper is primarily concerned with the latter group, for whom the just transition framework may be used as inspiration for a new kind of organizing, though the lessons from previous just transition efforts are applicable across the labour and social movement space. In the next section we look at a number of cases where this kind of community-level climate transition planning has already occurred.

Case studies in community transition planning

The cases in this section run the gamut from state-led, unjust transition programs to proactive, radical activism. In each case, however, community organizing (i.e., dialogue and coordination independent of government bodies and commercial entities) played an important role in empowering communities impacted by economic transitions. As we shall see, even where communities did not fully achieve their goals, practical lessons can still be drawn from their experiences. We begin with Australia’s coal-producing Latrobe Valley before turning to community organizing in the U.S. state of Kentucky, radical mapping exercises in Mexico and Ireland, and climate justice advocacy in Edmonton, Alberta.

Undercurrents of community power in Latrobe Valley, Australia

The Latrobe Valley, located in the southeastern state of Victoria in Australia, about 150 kilometres east of Melbourne, comprises half a dozen industrial townships that are home to about 73,000 people. The region has abundant sources of brown coal, or lignite, which has been extracted since the Second World War to provide electricity for the industries and metropolitan areas of the state of Victoria. In 2012, the valley still produced more than 85 per cent of the electricity used by Victoria’s industries and five million residents. While brown coal has provided abundant and cheap electricity for the region, it is an incredibly emissions-intensive and inefficient fossil fuel due to its low energy density and high water content.34

Since the 1980s, the region has undergone successive attempts at top-down restructuring, first through the privatization of the energy sector and more recently in relation to decarbonization. In order to cut costs and reduce debt in the 1980s, Victoria’s state-owned energy producer, the State Electricity Commission of Victoria (SECV), was privatized. The ensuing “rationalization” of the energy workforce slashed the share of employed people in the region by almost half between 1986 and 1994—from 20,420 to 10,997 workers in a local labor force of around 40,000 workers.35 The population also declined across the region, especially in industrial towns. Between 1991 and 1996, the population declined by 4,000 people, with nearly a third of men aged 25–44 years old leaving the region. During this period, the Latrobe Valley became known disparagingly as “The Valley of the Dole.”36

In the context of climate politics, community transitioning in Victoria has proven to be similarly divisive since the late 2000s. Representatives of major unions, including the Gippsland Trades and Labour Council (GTLC), environmental organizations, community groups, and government representatives at local and state levels, began meeting in Climate Change Forums in 2007 to discuss mitigation and adaptation measures. In 2011, a newly elected Labour government with ambitious climate goals established the Latrobe Valley Transition Committee (LVTC), a vehicle for stakeholder-based governance with the intention of elaborating a vision for the region’s future. This climate agenda ran into conflict with the Victorian state government of the time, led by a conservative Liberal-National alliance, which supported the coal industry. Tensions between the federal and state governments over climate issues (reflecting deep community divisions) stymied transition, while boundary drawings of “affected areas” clashed with local senses of place.37

After a destructive forest fire took hold of Hazelwood Power Station in 2014, Australia’s most polluting power plant, the community resolve to move beyond fossil fuels was strengthened. A Labour government with a social license for decarbonization was elected at the state level in 2014, establishing a new body, the Latrobe Valley Authority (LVA), a stakeholder-based group designed to help the region move beyond coal-powered electricity. Under a just transition framework, the authority has coordinated the provision of support for workers and businesses affected by the transition, particularly since the sudden closure of the Hazelwood Power Station in 2016, and offered recommendations on the nature and timing of community infrastructure developments to revive the local economy. The LVA era has been more successful than its LVTC predecessor in aiding workers with transition assistance. However, support gaps for some workers remain and community divisions over climate issues are not fully resolved.38

Just transition policy-making in the LVA has been complemented by community activism. The Gippsland Trades and Labour Council (GTLC) developed the model for an industry-wide job transfer scheme and formed an associated, but independent, Gippsland Worker Transition and Support Centre for workers in transition. These activities anticipated transition initiatives that were eventually implemented by the LVA when the Hazelwood Power Station closed in 2016. Other community groups include Voices of the Valley, the Gippsland Climate Change Network (GCCN), and the Earthworker Collective, who have all campaigned for fairer and more representative transition processes.39 Earthworker, a people-owned cooperative running a solar hot water factory in the industrial town of Morwell, organized an event called “Walk with the Valley”, travelling by foot between industrial towns to raise awareness and support for a just transition and to generate financing for the organization’s renewable energy manufacturing.40 Importantly, local community members have also organized to voice concerns about the environmental and health impacts of hosting the high-polluting coal industry. Tighter regulation in the valley has been enacted as a result, putting further pressure on firms with high emissions to clean up their act and accelerate decarbonization. In sum, community groups have not been passive in the face of wider structural changes, but have actively mobilized to support climate transitions.

Lessons from Latrobe Valley

The work of community organizers in the Latrobe Valley demonstrates how important it is to look beneath the surface of official transition policy-making. Government programs, whether successful or not, often overshadow the grassroots movements that are building economic alternatives and supporting communities in transition. Specifically, the work of the GTLC and other organizers highlights the importance of:

- Acknowledging the damaging legacy of past unjust transitions.

- Planning for disruptions in the local economy proactively, rather than reactively.

- Defining the geographic boundaries of transition in a manner that is sensitive to communities’ own place-based definitions.

- Facilitating an inclusive, rather than technocratic, social dialogue that ensures all stakeholder voices are heard, particularly in politically volatile regions that may otherwise frame environmental policies as oppositional to social and economic concerns.

- Allowing locals to set the pace and agenda for community dialogues to prevent consultation fatigue and further disempowerment.

- Moving beyond social dialogue—a necessary but insufficient process—to provide tangible supports for workers and communities in need.

- Taking an iterative approach to organizing that evolves with the needs of workers and communities in transition.

- Providing appropriate capacity and power to local governments, community groups, and individuals who are given transition responsibilities.41

Communities in Australia, like those in Canada, operate in a federal system with multilevel governance structures. This can create uncertainties over jurisdictional responsibilities—where does power lie? It can also create opportunities for communities to tap into governance structures and financing arrangements closer to home. Communities should set themselves the task of understanding and engaging the multi-level governance structures in which they will pursue their climate transition organizing.

Four decades of transition organizing in Kentucky, U.S.

The U.S. state of Kentucky is deeply implicated in the American energy transition. The coal industry has long played a key role in the economy, for better and for worse: 71 per cent of all coal mining jobs lost in the United States between 2011 and 2017 were lost in the Appalachian region, of which Kentucky is a part.42 On the other hand, the region is home to 27 per cent of energy justice programs in the U.S.43 Its most active group is Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC), a 40-year-old grassroots civil society organization focused on environmental and economic justice. In 2017, in response to partisan division over the federal government’s Clean Power Plan, KFTC launched the Empower Kentucky initiative, a US$400 million “people’s energy plan” set to reduce average electricity bills by 10 per cent and cut carbon dioxide pollution from Kentucky’s energy sector by 40 per cent.44 A product of consultation with 1,200 community members, it emphasizes local ownership of electricity and broader democratic participation in the formation of state government policy.45 According to the group, “Kentuckians do not need to wait for a federal mandate to begin to make progress.”46

KFTC has never waited for that mandate—not even in its earliest days as the Task Force on Appalachian Land Ownership. When floods wracked the border of Kentucky and West Virginia in 1977, the federal government failed to provide temporary housing for thousands of displaced people, especially on higher, mountainous ground that is used for private mineral extraction. Consisting of a group of ideologically diverse community members, organizers and academics, the task force realized that they needed to know who owned the land and mineral rights in order to understand the crisis and the roots of such inequity and extractivism. Its working groups found that only one per cent of Appalachians owned 53 per cent of the total land surface, with 40 per cent of surface land and 70 per cent of mineral rights held by corporations. While the federal government funded the initial research, it refused to publish the results. Local newspapers, independent publishers and churches from a variety of denominations stepped up to disseminate it.47

Through the Appalachian Land Survey, the task force would go on to cultivate an extensive local data system, building a grassroots and multi-scalar network that laid the foundation for KFTC’s transformative climate transition advocacy in the decades to come.

Even today, Appalachians express distrust towards “exclusionary” government transition initiatives like Eastern Kentucky’s Shaping our Appalachian Region (SOAR) initiative. They see non-partisan, statewide initiatives like Empower Kentucky as more successful at improving their social and economic conditions.48 Despite the dominance of the coal industry in Appalachian politics, KFTC built this trust through concerted action. In 1988, it successfully campaigned for a state constitutional amendment to end “broad form” mineral deeds and the preferential treatment of mineral (including coal) rights owners over property surface rights owners. The amendment received 82.5 per cent voter approval and passed in all 120 Kentuckian counties, with a total of 869,000 Kentuckians voting in favour—the first major disruption to coal hegemony in the state.49 More recently, KFTC organizers established the Renew East Kentucky initiative, working with East Kentucky Power Cooperative on a five-year project to increase energy efficiency. The initiative provides a range of programs to communities, including retrofits, at little to no up-front cost. Profits are returned to co-op members in the form of capital credits to be spent in the local economy.50

Throughout its history, KFTC’s commitment to iterative democratic culture has enabled such progress. Leaders have term limits, moving between roles in communications, organizing and policy. Community members, including many former coal workers, have access to workshops on public speaking, letter writing, lobbying, and strategic and organizational development to be put to immediate use. Empowerment is especially important in a political climate like Appalachia, where the dominance of a single industry can prevent coal workers from speaking up due to inherently precarious economic conditions.51 One training manual reads: “Our social and economic systems prevent ordinary people from recognizing and developing their talents and skills for leadership by celebrating the rich, powerful and well-educated as leaders.”52 Under Renew East Kentucky, KFTC members were trained and prepared to run for the boards of local electricity cooperatives and to lobby for public investments.53 After commissioning three studies on alternatives to coal, in 2010 KFTC successfully campaigned against East Kentucky Power’s plan to build a new coal-fired power plant.

Lessons from Kentucky

Kentuckians for the Commonwealth is four decades ahead of many communities that are seeking an inclusive transition to a lower-carbon economy. Its longevity is a testament to how thoughtful community leadership, backed by local knowledge, can sustain an effective progressive movement. KFTC has exposed deeply rooted injustices, envisioned economic alternatives, and worked toward long-term structural change in the face of a politically powerful extractive industry and ambivalent state government. KFTC’s experience highlights the importance of:

- Being sensitive to, and drawing connections to, historic injustices in the community.

- Identifying specific local issues around which to build the widest community coalition (e.g., unequal land ownership as a root cause of mineral extraction and subsequent flooding).

- Conducting grassroots research and investigative work, which can build long-term alliances with academia and labour organizations across regions and ideological divides.

- Training community members to lobby and participate in all levels of government, especially at the local level.

- Empowering community members to lead initiatives that are responsive to immediate and long-term community needs.

Radical (re)mapping in Mexico and Ireland

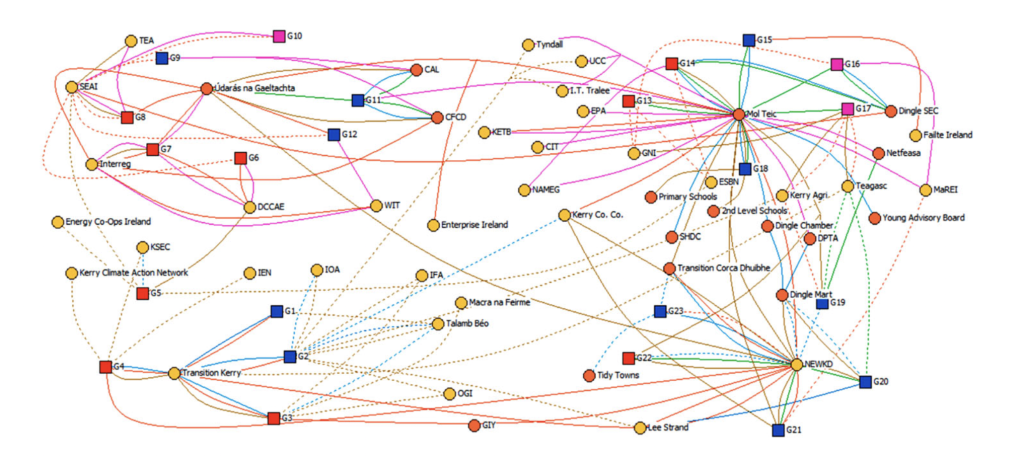

The southern Mexican states of Oaxaca and Yucatán and the port town of Dingle, Ireland, face very different transition challenges. Yet, in each, radical mapping practices have enabled communities to politicize and contest local energy transitions.54

Oaxaca and Yucatán are some of the world’s best locations for geothermal, wind and solar power generation and their governments are actively developing these industries. In 2015, Mexico passed an energy transition law that aims to generate 50 per cent of the country’s total electricity production from renewable sources by 2050.55 However, since the plan relies on private industry to fund initial investment costs, the government has granted corporations the rights to generate, transmit, distribute and commercialize energy infrastructure—rights that were previously the exclusive purview of state monopolies.56 Since 2015, the privatization process has entailed the dispossession of largely Indigenous-held lands for wind and solar farms. This process has been enabled by state “cadastral” mapping practices, which refers to a type of mapping that draws borders around different parcels of land based on their economic value—their potential for renewable power development, in this case—which is independent of social or environmental considerations.57

According to critics, these maps are poorly produced, laden with inaccuracies, and fail to include data that pertains to the structures of communal property and its complex subdivisions, such as Indigenous populations, electricity supply chains, land use and ownership patterns, territorial management, vegetation cover, and wildlife.58 When local social and ecological relations are not mapped, they are excluded from decision-making processes, which allows for private economic interests to dominate. Plans for renewable projects in Yucatán, in particular, have lacked public consultation.59 One recent study surveyed renewable industry workers and Zapotec communities to understand their perception of wind farms. The emergent wind industry failed to recognize the complexity of communal land relations, workers said, and they felt their expertise was not valued or put to use.60 Without respect and recognition of comunalidad, a reciprocity-based principle central to Zapotec cultural identity and political economy, conflicts between industry and Indigenous communities persist. The wind energy projects therefore reproduce colonial arrangements and pose a risk to communal livelihoods.

One organization has worked to produce “counter-maps” of the territories that the government has overlooked. Geocomunes, a Mexico-based activist group, works with local communities and organizers to collate information on dispossession, the privatization of land, and new low-carbon investments and infrastructure installed across the country. While local voice is easily obscured by abstract, technocratic mapping practices, such spatial tools are able to represent and give voice to divergent, competing interests. Geocomunes members include geologists and cartographers who invoke this place-based, granular research to highlight how hydro power and transportation projects systematically exclude Indigenous voices while risking significant social and environmental harm.61 There is little evidence that state and corporate actors have heeded their concerns. Still, it is indicative that grassroots knowledge production is vital in the attempt to translate across arenas of power. In Mexico, this community-led data project is the first of many steps needed to achieve an inclusive energy transition. More broadly, it is a lesson in how grassroots knowledge production is fundamental as communities determine the impacts of resource governance.

A different kind of radical mapping is at play in Dingle, Ireland. While Ireland is both Europe’s second-largest per capita carbon dioxide polluter and home to a long history of local co-operative organizing (in rural contexts, still known as the tradition of Meitheal), it has lacked community-led transition initiatives.62 However, Dingle Peninsula 2030, a low-carbon transition initiative led by civil society groups, researchers and industry, is turning the tide.

While Oaxaca and Yucatán are considered prime locations for the development of renewables, the rural peninsula of Dingle was chosen as a test site for transition because of its relative isolation in Ireland’s electricity network. “That made it very interesting for our industry partner, ESB Networks,” said researcher Brian Ó Gallachóir, “as a place where you could investigate and address challenges associated with electrification of heat and transport in a rural area. The community there wanted to explore what a low-carbon energy future might look like.”63

To bridge communication between the local community, industry and their research goals, the initiative used Net-Map, a tool that visualizes the networks that each partner belongs to and, implicitly, how they perceive other actors in that network.64 Although it is highly subjective, this process reveals community perceptions of power structures and power imbalances, and highlights who participates in transition processes. The perceived goals of each actor are also mapped to bring into focus possible conflicts and opportunities for collaboration under a shared vision.65

In Dingle, many new relationships between communities, industry and government have since emerged, ranging from a scheme to train community members as energy mentors to an initiative supporting 100 dairy farms to develop plans for retrofits and renewables.66

Like the Geocomunes maps in Mexico, the social maps in Dingle can help otherwise fragmented groups identify valuable forms of expertise and gaps in networks that can be productively bridged and to navigate social networks with more clarity—all of which lays the foundation for organizing.67 In Canadian communities, participants might be asked: who has influenced or can influence current political conditions in order to achieve a transformative climate transition for our community?

Lessons from Mexico and Ireland

Counter-mapping alone does not constitute a grassroots climate transition, but it is a valuable enabler of grassroots knowledge production and community action. These cases highlight the importance of:

- Supporting participatory forms of data production, such as social mapping, that make power visible and lay the groundwork for knowledge sharing and organizing.

- Using creative and visual tools to represent, anticipate and respond to internal and external conflicts, especially by representing and empowering voices that are underrepresented and disempowered.

- Addressing gaps in public data sources.

- Generating the evidence base for community-led alternatives to the status quo.

- Using social maps to identify relationships, including alliances and power imbalances, that might not be immediately visible or reflected in formal hierarchies.

Finding ways to accumulate and communicate community knowledge helps to shift popular narratives around energy transitions, enabling new conversations about place-based climate transitions that are grounded in the specific needs of each community. At their core, radical (re)mapping exercises and other forms of grassroots knowledge production encourage communities to establish voice, anticipate the impacts of incoming green investment projects, and therefore maximize benefits and minimize harms in line with those needs.

Community engagement outside the status quo in Edmonton, Alberta

Edmonton, the capital city of Canada’s “petro-province” of Alberta, faces a number of acute geographic, cultural and political problems in its transition to a low-carbon economy. The city produces more greenhouse gas emissions per capita than most other Canadian cities for a variety of reasons, including: (1) its dependence on natural gas and coal-fired electricity generation for power, (2) its low population density, which is related to a low-density urban layout (50 per cent of the entire residential building stock consists of detached houses), and (3) its cold weather requiring more energy for heating. Edmonton is also host to a mature petro culture, with high rates of residential energy consumption, high automobile dependency (both fuelled by relatively cheap fossil fuel prices) and a conservative political culture with wavering support for decarbonization. In addition, Edmonton is one of the fastest growing cities in Canada. The current population of one million inhabitants is expected to rise to nearly 1.5 million by 2044 and two million by 2065.68

The task for the municipal government to reduce emissions and ensure a just transition is a daunting one, but it has taken meaningful steps in that direction. The city established an Energy Transition Advisory Committee in 2015 and has since introduced a number of policies to reduce local emissions, including energy retrofit and solar energy programs, expanded electric vehicle and bike infrastructure, and the procurement of green electricity for municipal operations. In 2018, Edmonton hosted the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Cities Conference and co-created the Edmonton Declaration, which calls upon its more than 4,500 signatories to commit to urgent action to limit global warming to 1.5°C.69 Edmonton later produced the Edmonton Community Transition Strategy, a comprehensive roadmap for the city to reduce emissions and grow a dynamic green economy. That strategy for reducing emissions was paired with Climate Resilient Edmonton, a climate change adaptation strategy.

In the process, the municipal government undertook comprehensive public engagement, including 28 events (community drop in events, public workshops, stakeholder workshops, a Climate Action Youth Policy Jam, committee meetings and webinars) which led to over 850 conversations and 2,600 written comments.70

However, for all the progress made by the city in consulting with residents, developing strategies and implementing new policies, the municipal authority is relatively constrained in its capacities and ambitions by the concentration of financial and legislative power at the provincial level. One official from the Edmonton transition team described provincial budget allocations for city-level GHG reductions as “throwing pennies at an elephant.”71

The need for change at multiple levels of government has spurred significant climate action at the grassroots level in Edmonton. “Community leagues”, which are neighbourhood-level advocacy groups, have played a central role over the past decade in driving local renewable energy projects. They have successfully made use of provisional funds to finance renewable infrastructures while coping with the challenges of small organizations.72

Climate Justice Edmonton (CJE) is a small team with limited resources but it has organized a number of successful climate and just transition campaigns. In lieu of conventional lobbying, CJE has developed alternative political campaigns, such as supporting climate champions in elections, door knocking, organizing climate rallies73 and collaborative art installations,74 providing questions to citizens to ask candidates about climate issues, and advocating for progressive political parties to adopt ideas like a “climate corps” and a “green jobs guarantee” in their election platforms.75

CJE’s organizing efforts recognize that political power is not limited to elections and not limited to one level of government. Instead, it requires ongoing and courageous organizing. Speaking with oil and gas workers and local community members in Edmonton about climate issues can be difficult. Many residents’ livelihoods are on the table, while others are afraid to speak out against the fossil fuel industry. In its communications, CJE sets out a positive case for the green jobs of the future and shines a light on existing green initiatives in the Edmonton economy. CJE’s on-the-ground organizing complements another project in the region, the Alberta Narratives project, which has developed inclusionary language for talking about climate change and energy transition in Alberta.76

Lessons from Edmonton

In Edmonton, the municipal government is less of an obstacle than the provincial government and prevailing cultural expectations about the energy system. In response, community climate organizers have emphasized public education and electoral interventions at multiple levels of government. These efforts highlight the importance of:

- Creating alternative and parallel forms of social dialogue where formal channels are blocked or insufficient.

- Determining structural constraints to inclusive transitions so that community organizing can focus limited resources on the right areas.

- Taking a multi-dimensional approach to making political change—not just fighting elections, but also building community power.

- Building a positive case, expanding the collective political imagination and developing a vision of radical alternatives to the fossil fuel economy.

Existing initiatives to support community transition planning

As we have seen, grassroots climate transition organizing is already taking place in communities around the world. While many of these groups have done so independently, there are also a growing number of organizations providing grassroots groups with resources and guidance for more effective mobilizing. In the UK, for example, the Transition Network convenes “transition hubs” to bring various community groups together on issues of joint concern.77 In this section, we review three other initiatives supporting community transition planning and draw further lessons for Canadian communities. We begin with the grassroots Climate Justice Alliance and philanthropic Just Transition Fund, both U.S.-based, before turning to the work of Canada’s Tamarack Institute.

Climate Justice Alliance

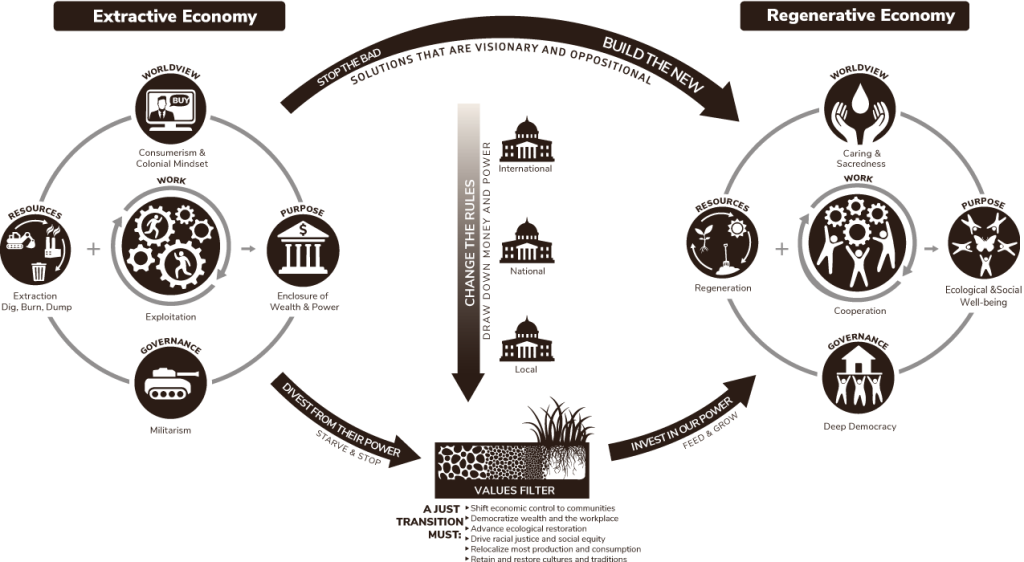

The Climate Justice Alliance (CJA) is a coalition of mostly U.S.-based groups mobilizing for grassroots climate transitions that foreground racial, gender and economic justice. CJA adapts its understanding of just transition from the Just Transition Alliance, a group of frontline workers and “fenceline communities”,78 which defines just transition as “a vision-led, unifying and place-based set of principles, processes, and practices that build economic and political power to shift from an extractive economy to a regenerative economy.”79

The group’s emphasis on place-based processes underlines the need to define community boundaries at the beginning of community-led transition planning. The CJA rejects what it calls “false solutions.”80 False solutions, according to the CJA, (1) extract and further concentrate wealth and political power away from communities, (2) continue to poison, displace and imprison communities, and (3) reduce the climate crisis to a crisis of carbon emissions alone.

The CJA places a clear emphasis on envisioning fairer and greener economies. Just transition, to this group, “describes both where we are going and how we get there.”81 The desired end point, for the CJA, is a regenerative economy, rather than an extractive one. In a regenerative economy, waste is minimized and the loops between production and consumption cycles are closed. Regenerative economies break from extractive economies, which follow a linear model of resource management based on a “take-make-dispose” model.82

Lastly, in the CJA formulation, distributive, procedural, and restorative principles of justice are held in high regard: “The transition itself must be just and equitable; redressing past harms and creating new relationships of power for the future through reparations. If the process of transition is not just, the outcome will never be.” This underlines the need to design inclusive processes and determine structural constraints. “New relationships of power” can only be built if status-quo power relations are called into question.

In practical terms, the CJA engages directly with workers and communities in a variety of ways. It hosts workshops and produces toolkits to educate and empower local organizers.83 The CJA also convenes dialogues between relevant stakeholders, including lesson-sharing meetings between organizers in different communities. Although the CJA is clear about its principles, it is not prescriptive in its solutions. It encourages each community to identify and champion its own path forward. The CJA’s interventions help communities to better prioritize projects, to design those projects effectively, and to make interventions at strategic moments.

Lessons from the Climate Justice Alliance

With dozens of partners across the United States, the Climate Justice Alliance has emerged as an important organizing hub for the U.S. climate justice movement. CJA’s approach highlights the importance of:

- Foregrounding Indigenous leadership and frontline communities to make connections between climate, racial, economic and gender justice.

- Emphasizing place-based principles, processes, and practices over one-size-fits-all approaches.

- Prioritizing distributive, procedural, and restorative justice over centralized decision-making.

- Identifying structural constraints to community problems and envisioning new relationships to those power structures.

- Orienting action around a clear and positive vision for the future—regenerative economies—in place of the current model of exploitation and extraction.

In the CJA’s formulation, justice is not limited to dealing with the aftermath of industry closure. Justice is about redesigning the entire economic structure in a more equitable and sustainable way.

Just Transition Fund

The Just Transition Fund (JTF) is a U.S.-based philanthropic organization. It was established in 2015 to support communities in accessing federal funding through the Obama-era Partnerships for Opportunity and Workforce and Economic Revitalization (POWER) initiative, which focused on coal communities. It has since moved beyond POWER to track other relevant legislation and policies for communities undergoing climate transitions, such as support for rural energy cooperatives and extending access to broadband. The JTF’s dedicated Federal Access Center has so far connected community partners to $342 million in public and private funding for long-term planning.84 In doing so, it emphasizes the need for government support in the early stages of planning for energy transitions, not just after sites of extraction and fossil fuel-based energy generation have closed or when layoffs have been announced.

The JTF identifies and fills skill gaps in communities seeking to navigate highly complex funding applications by identifying new and appropriate funding programs, tracking and communicating relevant legislation, understanding application requirements, connecting with agencies, and developing proposals. Recognizing that successful applications hinge on the development of long-term transition planning, the JTF has also provided an online blueprint for transition with four iterative steps: taking stock of community capacities; identifying and engaging all members of a community; developing “measurable, meaningful and objective” metrics to measure progress towards shared goals; and taking action, which starts with accessing a number of possible federal grants.85 The blueprint provides specific, generative and valuable questions for communities at each of these stages, with the JTF performing a vital role in the “taking action” stage.

The Just Transition Fund provides a crucial service in helping communities mobilize around the idea of a just transition. However, communities must necessarily look beyond the JTF’s focus on existing government programs to avoid reproducing a unidirectional core-periphery relationship. While many federal grant programs have been sustained and strengthened by continuous, community-led forms of organizing, the JTF neither acknowledges nor encourages communities to uncover these histories. For instance, the Black Lung Disability Trust Fund, which compensates coal miners with pneumoconiosis and is financed by an excise tax on coal, exists because of lobbying by United Mine Workers in the 1960s and 1970s. It has been sustained by campaigning by groups, including Kentuckians for the Commonwealth as recently as in 2022, with the reintroduction of the Black Lung Benefits Improvement Act.

Without this context, the presumption is that communities must rely exclusively on external public and private funding sources to organize and are, therefore, more likely to adapt community needs to the priorities and ideological positions of current administrations (or to private entities hoping to exploit energy transitions for commercial gain).

It is important for communities to develop shared goals and to take stock of existing capacities, but these are shaped by pre-existing conditions—whether explicit or implicit. Communities can be more specific and responsive to shared goals by also developing shared histories that reveal the persistent but contestable injustices standing in the way of an inclusive transition to a cleaner economy. As our other case studies illustrate, developing alternative data sources, nurturing relationships with other communities, and interrogating histories create new opportunities to develop metrics and shared goals, expand perceptions of what is possible, and better understand the contested landscape of external funding sources.

Lessons from the Just Transition Fund

Government and industry-led transitions are not always just; mapping historic, ongoing and potential forms of conflict between government, industry and communities in the funding process itself is a vital opportunity for ensuring grassroots voices are not diluted or silenced when contestation inevitably arises. The strengths and weaknesses of the JTF highlight the importance of:

- Building capacity within communities to interface with formal power structures and to access available funding and, therefore, strategically voice demand for greater funding.

- Planning proactively for industrial change instead of waiting for sunsetting industries to disappear.

- Understanding government funding programs as one element of an inclusive climate transition but not as a replacement for community organizing.

Indeed, grassroots organizing is often the reason why public funding programs are created and sustained in the first place. Communities must recognize that such funding sources are contestable, for better or worse, and that the present availability of funding should not place limits on the ambition of community-led transition planning.

Community Climate Transitions network

The Tamarack Institute is a Canadian organization working to catalyze community change. In recent years, Tamarack has built a Community Climate Transitions (CCT) network aimed at creating relationships between and building capacity in cities, communities and organizations across Canada to contribute to a just and equitable climate transition. The organization hosts webinars and events, offers specialized coaching, and produces publications to share best practices with its members.

In their CCT program, Tamarack has specifically linked climate organizing to the broader principles of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).86 According to Tamarack, 100 per cent of participating communities are advancing the SDGs locally while half have generated at least one impact story related to systems change. The network provides a platform for cities and communities to build capacity and communicate with one another about progress made in developing climate policies.

Tamarack’s approach to just transition organizing has its limits. Little attention is given to organizers seeking to identify and challenge the power structures that are obstructing a truly just transition in their communities. While the institute correctly identifies the intersecting crises of climate change and injustice facing many communities, it overlooks the importance of political and economic power. The organization makes scant reference to the centrality of fossil fuels in the climate crisis and the power of the fossil fuel industry in Canada’s political system.87 Notably, one of Tamarack’s principal funders is the Suncor Foundation, which is the charitable arm of Canadian oil sands producer Suncor Energy.88

The institute’s focus on the UN Sustainable Development Goals, as opposed to a more radical agenda of climate justice and deep decarbonization, is also a concern. The SDGs have been criticized for a variety of reasons, including the apparent conflict between environmental and economic development priorities.89 It is unclear whether Tamarack’s agenda is compatible with the vision of a zero-carbon, inclusive economy championed by most just transition advocates.

Lessons from the Community Climate Transitions network

As a network for community organizing, the Tamarack Institute plays a potentially important role in local transition efforts across Canada, but its ties to big oil undermine its effectiveness and limit its reach. The strengths and weaknesses of the institute highlight the importance of:

- Educating organizers and training community members so that they can take local action.

- Convening disparate communities to share lessons and approaches from their own work.

- Identifying where corporate and government power influences and undermines grassroots efforts, even where funding and support are provided.

Community climate transition organizers should not feel restrained by frameworks that uncritically defend economic growth without a commensurate focus on an equitable, regenerative economy.

Best practices for grassroots climate transition organizing

Every transition is unique, but as our case studies illustrate, there are common threads in the work of community climate organizers and in the work of the groups that support them. We identify 12 general lessons from these case studies, which we outline below and which inform our action framework in the following section.

Start early. The broad strokes of transition are foreseeable before a plant is shuttered or anyone is laid off. Proactive policies that build community power and economic alternatives before they are needed are more likely to succeed than organizing in the wake of economic shocks.

Clarify community. The bounds of a “community” are often taken for granted but, when it comes to organizing work, it is important to identify who exactly is participating and for whom the movement is working. Establishing bounds does not mean excluding allies and external stakeholders from the process. Rather, it is about focusing the organizing effort around the people at the core of the transition.

Reckon with history. Many governments are quick to gloss over historical injustices and their legacies—from slavery to colonialism to gender-based violence and more—but community organizers cannot shy away from these realities. Likewise, communities must be clear-eyed about how and why past transition efforts did or did not succeed. This includes historic and existing organizing efforts, such as by Indigenous Peoples and people of colour who are too often brought to climate coalition tables as an afterthought. It is important for communities to come to an understanding of how they got where they are so that they can better move forward together.

Promote community knowledge. The people with the greatest understanding of a community’s needs, challenges and opportunities come from within that community. Their knowledge is an invaluable organizing resource. Giving a voice to historically underrepresented and disempowered groups (and mapping historic and existing organizing around social and environmental justice) is especially important for challenging established narratives.

Employ democratic processes. Community power, as an ideal, can only be achieved through a truly democratic process. All members of an affected community must have a say in its direction and disagreements should be handled respectfully and in good faith. Moreover, community organizing must be iterative, which is to say that the specifics of decision-making processes must evolve with the community over time.

Nurture relationships and build broad coalitions. Organizing in isolation is possible, but it is harder and less likely to succeed than joint organizing efforts. Communities should build relationships with potential allies, from neighbouring communities to academics to small businesses to journalists. Partnering with the labour organizers who are pushing for a just transition for workers is an obvious starting point for many communities. Building relationships between different kinds of movements makes them more resilient and enables coordinated action against, for example, higher levels of government.

Develop alternative data sources. Gatekeepers in government and the private sector, which have a vested interest in the status quo, often curb what is considered “possible”. Critical work in history, economics, climate science and other fields—whether community-generated or in partnership with academics and other experts—can help reframe the narrative about what is truly possible in a given community.

Build capacity and confidence. Movements that succeed over the long-term invest in themselves through ongoing training and capacity-building efforts. Community members must be empowered to take on leadership roles of their own, whether as organizers, lobbyists, researchers, spokespeople or otherwise.

Map relevant power structures. Building community power requires an understanding of the forces arrayed against historic and current community organizing. Often, power rests in overlapping levels of government and communities must learn how to anticipate and navigate these complexities. Elsewhere, corporate power is the greatest consideration and communities must employ a different toolset for asserting themselves. In practice, corporate and political power often intersect, as is sometimes the case between property developers and municipal governments. On the other hand, progressive municipal governments often prove to be essential allies in providing resources and leadership to community organizers, especially when it comes to small communities taking the fight to higher levels of government.

Envision a better future together. One of the failures of governments’ interpretation of the just transition concept is that it is an inherently pessimistic concept; “just transition” only emerges when livelihoods are being taken away. Crucial to community organizing efforts is a vision of a positive alternative—the collective “Yes”, the inspiring and hopeful act of envisioning the fairer, more connected world on the other side of transition. Not only can a shared vision better win political support, but it also provides concrete guideposts for community demands and policy change.

Move from dialogue to action. A robust social dialogue is essential to community organizing and plays a pivotal role in every case that we have studied. However, where organizing stops at dialogue—as is often the case in government stakeholder consultations—it can actually undermine grassroots efforts by eroding confidence in the process. Organizers must instead pursue tangible campaigns and projects that make change in the community or, at a minimum, demonstrate to community members that positive change is possible.

Emphasize public ownership and control. New infrastructure investments are a huge piece of the energy transition, whether in the form of wind farms for power, energy efficiency retrofits for homes, safe paths for active transportation, or resource centres for workers in transition. For a truly inclusive transition, as much of this investment as possible should be directed by and, ideally, owned by the communities it serves. Public ownership builds power and ensures the primary beneficiaries of community investment are the communities themselves.

The 5D framework

Inspired by the idea of a just transition for workers, and drawing from the best practices outlined in the previous section, the “5D” framework below lays out five discrete stages of organizing for a community-led climate transition: (1) defining community, (2) designing processes, (3) dreaming up a greener future, (4) determining constraints and (5) delivering alternatives. At each stage, we offer guiding questions that can help communities focus and organize their efforts.

This framework is intended not only for communities that have been historically dependent on fossil fuel production, such as coal and oil towns. It is also for communities that do not produce coal, oil or gas but still depend on fossil fuels for their well-being. Every community across Canada today uses fossil fuels, so every community must consider how best to transition toward climate-safe alternatives. For primarily fossil fuel-producing communities, the focus will likely be on industrial alternatives. For primarily fossil fuel-consuming communities, the focus may be on issues such as housing and public transit, around which organizing may already be occurring but without a climate lens.

Individual communities may tackle the five D’s in a different order or adopt a different organizing tool than the roadmap we suggest. There is no shortcut or one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to building community power. Indeed, achieving an inclusive climate transition at the community level will always require a great deal of energy and creativity. The framework presented below is just that—a framework that can help guide communities interested in mobilizing the idea of an inclusive transition toward a sustainable and inclusive economy for all.

Define community

“Community” is an admittedly vague term. It can refer to a group of people organized by place (such as a neighborhood community), by identity (such as a racialized community), by shared economic interest (such as a community of workers) or by any number of other principles. What matters most is that the bounds of the relevant community are defined (with the understanding that these bounds are likely to evolve over time). If the bounds are unclear—if the purpose of organizing is reduced to “transition” in the abstract—it becomes difficult to develop and advance specific, concrete actions that serve the community in question.

Stakeholder mapping is a valuable practice that can clarify the relationship between different actors in and around a community. It involves creating a visual representation of internal and external stakeholders, including their levels of interest and influence in the community. Internal stakeholders become key players in the movement, while external stakeholders may play a vital role as allies. Communities should be especially aware of any local unions, labour councils or worker collectives organizing around the idea of a just transition for workers, which present a natural opportunity for collaboration.

At this stage, it is also important to begin mapping and defining transition risks within the community. Arriving at a good understanding of “where we are now” is essential groundwork for the later development of alternatives.

Key questions to consider at this stage include:

- What are the most carbon-intensive activities in the community? How do we use fossil fuels in our day-to-day lives?

- What are the greatest climate risks in the community? How do we need to adapt to extreme weather, changes in investment patterns, and the rise of climate refugees, among other issues?

- How is the community likely to be affected by the transition away from fossil fuels and toward clean energy alternatives?

- Who in the community is most vulnerable to transition?

- Who in the community has the capacity (and interest) to take action?

- Who holds power in the community? Who does not?

- Who are potential allies outside the community?

- How can communities plug into and reinforce the labour movement’s just transition organizing?

Answers to these questions can help to identify the focal points and bounds of a community for the purposes of organizing around an inclusive climate transition.

Design processes

Once a community has been delineated, its members must design internal organizing processes that are themselves inclusive rather than exclusive. Every member of a community should have a voice. Inclusive organizing processes also tend to be iterative rather than decisive. As the community and its understanding of a climate transition evolves, so should its governance structure.

Social dialogue, which refers to an open exchange of information and ideas between various stakeholders, is one approach to climate transition organizing. However, social dialogue alone is insufficient and can even be counterproductive in the absence of further action. Inclusive organizing processes should be designed with an emphasis on social power, which means they are action-oriented rather than exclusively consultative. One important element of building power within the community is through training, education and other efforts to empower individual community members to take on leadership roles. Another is community ownership of energy and transition infrastructure, which we discuss in more detail below.90

In some contexts, such as community associations or the labour movement, these processes may already be well established. In others, organizers will need to build new social infrastructure to support grassroots climate organizing.

Key questions to consider at this stage include:

- Who is responsible for recruiting and coordinating community members?

- How can members of the community make sure their voices are heard?

- Who may speak on behalf of the community?

- How will organizers engage with affected members of the community who are not directly involved in climate organizing?

- Which national or regional organizations offer support to community groups like ours? What training or resources can they offer our members?

Answers to these questions can help a community better work together to advance shared priorities.

Dream up a greener future

Once a community is defined and inclusive organizing processes are in place, the community must begin the process of developing a community roadmap, which is an organizing tool that clarifies the community’s goals and most likely pathways for achieving them.

That process begins by imagining a greener future together. An inclusive transition cannot merely be an exercise in fairly distributing the costs of moving away from fossil fuels. It must also be a process that creates new opportunities in the shift toward a cleaner and more inclusive economy. Collective visioning starts with the identification of broad, long-term shared goals. While many of these goals are likely universal—good green jobs, carbon-neutral buildings and zero-emission transit options, for example, are all common and worthwhile goals—every community will also have its unique needs and aspirations. Clarifying those goals together lays the groundwork for more tangible climate transition planning.

Next, communities must undertake the challenging but crucial work of developing pathways between the community as it exists today and the community’s own vision and goals. That may involve a certain amount of research and analysis, which may require outside expertise to work through the specifics, but it should always remain grounded in the community’s own organizing processes. While a detailed economic plan is not strictly necessary, to the extent possible the community should try to offer a clear and considered political-economic analysis to support the path forward.

Key questions to consider at this stage include:

- What green industries already exist in this community? How can they be nurtured and expanded?

- Which industries in this community can viably transition away from fossil fuels? What support will they need to transition successfully?

- Which industries in this community cannot transition away from fossil fuels? What support will workers need to transition to new industries?

- What inputs or investments are needed today to achieve long-term transition goals?

- What is the extent of community ownership today? What opportunities exist for community ownership in a greener economy?

- What training or reskilling is needed to best position the community to take advantage of a transitioning economy?

- What social support will be needed to smooth the inevitable dislocations caused by any economic transition?

- What historic injustices can be remembered and remedied through the transition process?

Answers to these questions can help a community identify and coalesce around new economic pathways.

Determine constraints

The community roadmaps developed in the previous stage are prefigurative. They outline where a community wants to go and how it thinks it can get there. The next stage involves identifying and mapping any constraints that must be overcome for the community plan to succeed.

Political constraints include the concentration of power and resources in central authorities, especially where those authorities have been captured by corporate and elite interests. Governments can fail to support or even actively interfere in community organizing where its priorities differ from those of the community. The Net-Map methodology (discussed in the Ireland case study above) is one approach for identifying political constraints. By inviting community members, allies and stakeholders to visualize social and power relations in the community, you can uncover hidden conflicts and potential for cooperation.

Geographic constraints include the built environment, such as locked-in infrastructure for personal vehicles, as well as the limits of the natural world. For example, not every community is equally suited to renewable energy generation, but every community can find better ways to move around and consume less energy.

Cultural constraints include expectations about consumption, democracy and the possibility of transformative change. Where cultural expectations are inflexible or entrenched, as in automobile dependence, some climate transition pathways can be viewed as a threat to peoples’ way of life.

Key questions to consider at this stage include:

- For each of the pathways in our community roadmap, what forces are aligned against change?

- What additional resources or support would be necessary to overcome those constraints?

- If our community roadmap were to fail, what would be the most likely reason, in retrospect? How can we proactively address those weak points?

- Who else faces these constraints? Are they untapped allies?

Answers to these questions can help refine a community roadmap from an aspirational document into a practical organizing tool.

Deliver alternatives

The final stage of grassroots climate transition organizing is to mobilize for change. Once again, the specific approach will depend on the community in question, the scope of their transition aspirations, and the nature and extent of constraints. Workers might take the fight to employers to win green clauses in contracts or to implement concrete transition plans for fossil fuel facilities. Activists might lobby politicians to provide funding for community transition projects or to champion these projects to higher levels of government. Community leaders might create networks of mutual aid and investment to enable low-income community members to participate directly in emission-reduction projects. In each case, however, the crucial point is that the community attempts to deliver real alternatives to the status quo.