Executive summary

Canada’s federal response to gendered impacts of the pandemic was on par with other high-income countries. Roughly 30 per cent of programs introduced between March 2020 and June 2021 were “gender-sensitive” defined as measures that addressed, in full or in part, gendered risks and challenges associated with the pandemic including increased violence, low income and precarity, and heightened care demands.

But its particular policy mix stands out with a greater emphasis on measures that supported women’s economic security needs and unpaid care compared to other peer countries. In total, gender-sensitive programs represented approximately $42.6 billion (or 11.6 per cent) of total federal pandemic expenditures.

Roughly 30 per cent of pandemic programming introduced by Canada’s 10 provincial governments also addressed the gendered impact of the pandemic, but their financial contribution was considerably smaller. Net provincial spending (excluding federal transfers) totalled $13.6 billion—one-quarter of combined federal and provincial spending ($57.5 billion)—on gender-sensitive programs.

The scale and strength of the different provincial policy responses varied widely. Provinces, on average, spent $357 per person on gender-sensitive measures compared to $1,155 per person by the federal government. But eight of the 10 provinces fell below this benchmark; six of the 10 provinces delivered very weak responses, spending less than $100 per capita on gender-sensitive measures.

The level of net provincial spending ranged from a very low $50 per capita in Alberta to $844 per capita in British Columbia, which was more than twice the provincial average.

Level of income played a key role shaping and constraining gender-sensitive responses to the pandemic. In Canada, it was the federal government that stepped forward to finance the bulk of Canada’s pandemic response.

But Alberta, the wealthiest province in Canada, spent only 1.2 per cent of its GDP on its pandemic response and a scant 0.1 per cent on gender-sensitive programming. Likewise, Ontario and Saskatchewan delivered anemic pandemic responses given the scale of the challenge and the resources at their disposal.

Had it not been for federal transfers tied to specific goals, such as the provision of child care or services for vulnerable populations, the number of provincial programs qualifying as gender-sensitive would have been much smaller, indeed potentially non-existent.

Such as it was, there were significant policy gaps that neither provincial nor federal programming addressed. The COVID-19 crisis has definitively illustrated what’s possible with strong public leadership. The imperative now is to apply the lessons of COVID-19 in service of a more sustainable, resilient and gender-just future, ensuring that those who bore the brunt of the pandemic are not again left behind.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has taken a huge toll on women.1 Millions of women were working in public-facing jobs that were most affected by necessary public health closures. Millions more laboured on the front lines, sustaining our communities while juggling an enormous increase in unpaid labour and care at home. Significant gaps in our market-oriented care infrastructure and the failure of governments to take effective action further amplified the pandemic’s impacts—and resulting stresses—on women and marginalized communities, including increased violence, greater isolation, ill health and learning loss, heightened economic insecurity, and loss of access to vital community supports.2

Canada’s experience has not been unique. Feminist researchers, community advocates and progressive movements from around the world have documented the myriad of ways in which the crisis has impacted women’s lives and further undermined the position of marginalized communities that are already affected by institutionalized poverty, racism, ableism and other forms of discrimination. They have also documented the ways in which established systems of support—from health care to employment standards to income security—failed to support those who bore the brunt of the pandemic.

At the beginning of the pandemic, all countries took steps to respond to the health crisis and mitigate the ensuing economic and societal shocks. These efforts included measures to lessen the negative impacts of the pandemic on individuals, businesses and community services. Yet, as UN Women has documented, very few a put in place a “holistic gender response”3 to the unfolding crisis and the erosion of women’s rights and well-being. Fewer still considered the unique position or experiences of marginalized women or gender-diverse people in their recovery programs.

This report takes stock of Canada’s response to the pandemic—covering the period from March 2020 to June 2021. Guided by the UNDP-UN Women’s Global Gender Response Tracker,4 it examines whether published plans incorporated a gender-inclusive lens and the type and mix of gender-sensitive pandemic programming introduced. What kind of measures did federal and provincial governments put in place to mitigate the negative impacts of the pandemic on women? How did these efforts compare—to each other and to other peer countries? What factors potentially account for the similarities and differences between different jurisdictions? The last part of the report provides an overview of the findings and presents six policy take-aways for moving a gender-just recovery forward.

Canada provides an important case study because it has been held up as a global leader in the pursuit of gender equality, one of the comparatively few countries that has actively pursued gender mainstreaming through the introduction of gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) in federal policy processes, including gender budgeting legislation in 2018, and investment in disaggregated data collection. However, as evidence gathered for this report shows, these actions, while necessary, were not enough to deliver on the promise of gender-justice—certainly not in a country where the response to the pandemic hinged on subnational levels of government, many of which were wholly silent on the pandemic’s gendered impacts. Our findings are consistent with the critique developed by feminist scholars5 about the limits of GBA+, and gender mainstreaming more broadly, as gender-transformative policy within the context of a neoliberal policy paradigm that prioritizes “participation in the formal economy, technical ‘solutions’, and narrow definitions of gender.”6

There are clear limitations to an analysis that focuses on the number and stated objectives of pandemic programs captured from a review of budget documents and government announcements on the public record. There will inevitably be gaps due to a lack of available information, underreporting or overreporting of measures, or a lack of data altogether—especially about the intersectional dimensions of existing measures.7 This is true of most policy trackers, including the Global Gender Response Tracker used in this analysis. Moreover, a bird’s eye policy analysis of this type further compounds this problem by glossing over the lived experiences of women facing overlapping forms of discrimination, focusing on the policies themselves and not their individual or community-level impacts.8 It does not fully address critical differences between women by Indigenous status, age, class, race, or disability status that are vital to our understanding of women’s inequality and systemic disparities, as well as the workings of the state itself as a source of oppression.9 The primary focus on women also tends to obscure consideration of gender-diverse people and their experiences.

Evidence on pandemic impacts is now slowly emerging, but much remains to be done. What a tool like the Global Gender Response Tracker and our comparative analysis can offer, however, is insight into common themes, significant gaps, and potential policy drivers important to the discussion of policy lessons and missteps, and thoughts about how to leverage pandemic innovation to much greater effect.

Canada’s gender pandemic response: Did it measure up? is part of a larger project called Beyond Recovery, which is working to support and advance a gender-just recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. The project’s goals are to document and analyze women’s experiences, with a particular focus on those of marginalized women in hard-hit sectors, and to provide evidence-based policy proposals to ensure those who are most impacted in this pandemic are front and centre in Canada’s post-pandemic future. Please find the Beyond Recovery’s Bumpy Ride Labour Market Updates at the CCPA’s www.monitormag.ca. Additional research and sector case studies will be published in 2024 and posted on the forthcoming Beyond Recovery website.

Examining Canada’s gender pandemic response

Feminist recovery plans

As the scope and scale of pandemic impacts emerged, feminist organizations around the world led the call for a feminist recovery that would both respond to immediate needs and advance structural reform, ensuring a gender-just recovery for everyone.

Here in Canada, B.C.-based Feminists Deliver was one of the first groups to release a feminist recovery plan in July 2020.10 Other groups included the YWCA Canada, in collaboration with the Institute for Gender and the Economy at the University of Toronto,11 Oxfam Canada,12 West Coast LEAF,13 and the City for All Women Initiative in Ottawa14—all of whom presented intersectional plans for an inclusive recovery. Some initiatives focused on the unique situation of particular groups. The Canadian Feminist Alliance for International Action (FAFIA) and Dr. Pamela Palmater worked together to document the experiences of Indigenous women and the failure of the Canadian state to uphold Indigenous Peoples’ right to self-determination in their response to the pandemic.15

These, and other feminist recovery plans, stressed the imperative of centring the perspectives and needs of the most marginalized at the heart of the policy process and facilitating people’s active participation in decision-making. As the Hawai’i State Commission on the Status of Women’s plan, Building Bridges, Not Walking on Backs, stated, “[t]he road to economic recovery should not be across women’s backs.” Rather, a recovery plan must address the issues of exclusion head on and set the stage for deep cultural change. “These problems can be overcome, but we must first admit that they exist. When those providing aid are held to task by the community to address existing power relations, reaching everyone according to their need is perfectly possible.”16

The call for a feminist recovery was also taken up within the academic community17 and among international agencies, such as UN Women,18 ILO,19 OECD,20 and the European Parliament.21 Feminist leaders and researchers in these organizations quickly mobilized to both amplify community voices and provide guidance for developing, tracking and evaluating the impact/efficacy of gender-inclusive pandemic policy and tackling associated policy gaps and systemic barriers confronting marginalized communities.22

This research collectively stressed the importance of continued monitoring of the pandemic’s differentiated impacts on women, men and gender-diverse people, supported by the collection of disaggregated data and the application of a truly intersectional lens to ensure all policy is informed by the best available evidence.23 It also argued for a combination of “proactive and targeted” measures to address specific challenges faced by different women (e.g., gender-based violence, lack of supports for caregiving) as well as concrete strategies to better integrate “gender-inclusive considerations” into broader policy-making processes and recovery strategies.24

How did governments respond to these challenges? What was the experience in Canada?

An analysis of federal and provincial pandemic announcements and related government budgets predictably reveals large variationwith respect to the degree to which different governments 1) took into account the disproportionate impact of the crisis on marginalized people, and 2) pursued gender-sensitive programming.

The federal government, for its part, clearly acknowledged of the gendered character of the COVID-19 crisis in its policy statements. It was one of a small group of countries, as reported by the OECD, that explicitly undertook gender impact assessments in the design and delivery of its pandemic and recovery response.25 It applied a gender lens to its pandemic response and recovery efforts—as stressed by the finance minister and evidenced by the establishment of a Women and the Economy Task Force,26 the completion of Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) analyses27 of main government policies, including its Fall 2020 Economic Statement and its 2021 budget,28 29 and a historic investment for the development of a Canada-wide early learning and child care system.30 In February 2021, it established a Feminist Response and Recovery Fund in support of community organizations and researchers working to tackle systemic barriers facing marginalized or underrepresented women.31 These efforts were supported by Statistics Canada, which had been tasked with developing and producing disaggregated data for the purposes of gender budgeting and reporting on Canada’s Sustainable Development Goals, housed in a newly created Gender, Diversity and Inclusion Statistics portal.32 Under these initiatives, Statistics Canada is expanding the sources of information available on Indigenous Peoples, racialized communities, people with disabilities and other marginalized groups.

The federal government also took steps to ensure women’s representation in decision-making bodies that were overseeing the response to the pandemic. Of the six task forces that were established to manage the public health crisis, including the COVID-19 Vaccine Task Force and the Cabinet Committee on the Federal Response to the Coronavirus Disease, over half of all members were women (54%), considerably above the global benchmark (24%). Four of the six committees had male/female co-leads (there were no female-only leads).33 Research has shown the importance of including diverse voices of all kinds in decision-making, to bring different lived experiences to the table and different leadership styles and methods of work.34 This proved true in response to the pandemic itself: Several women-led countries quickly emerged as the most successful at containing the spread of the coronavirus.35

The application of a gendered lens to recovery efforts was considerably more varied among the provinces that coordinated the community-level service response to the pandemic and recovery.

Quebec was the only province to publish a Plan d’action pour contrer les impacts sur les femmes en context de pandémie in advance of its 2021 budget (see Box 1).36 Another three provinces formally undertook a GBA+ review of their proposed recovery plans (New Brunswick, British Columbia and Newfoundland and Labrador37), one indicated their intent to do so (Prince Edward Island), while the rest made no mention of the need for such an analysis in their public documentation and announcements—including Ontario, Nova Scotia, Manitoba, Saskatchewan and Alberta.38

Looking at the 10 provincial 2021 budgets, the discussion of the impact of the pandemic on women or other marginalized groups varied (see Table 1). A count of the use of the word “women” or “gender” ranged from no mentions at all in Saskatchewan and Prince Edward Island to 83 mentions of the word “femmes” in Quebec’s 2021 budget and 215 in its gender recovery plan. The considerably longer federal 2021 budget mentions “women” 669 times and the word “gender” 757 times. This is a simple but telling metric: the differential impact of the pandemic was not a theme, much less a funding or policy priority, in many provinces.

There were two other related policy initiatives of note. In Budget 2021, the Ontario government struck a Task Force on Women and the Economy to address “the unique and disproportionate economic barriers women face, particularly in an economy that will look different after COVID‐19.”39 Comprised largely of representatives of the business community, the task force hosted a series of roundtable discussions with stakeholders in the summer of 2021, touching on entrepreneurship, women’s under-representation in STEM fields, and supports to assist with entering or re-entering the workforce. Recommendations were prepared for the Ontario minister of finance and the associate minister of children and women’s issues. No public summary or analysis was released, nor was there any indication that the exercise had a meaningful impact on Ontario’s recovery programming. (The federal Task Force on Women and the Economy was also quietly disbanded a year after its announcement).

The Alberta government commissioned a study in spring 2021 from the Premier’s Council on Charities and Civil Society to provide advice on how civil society organizations (CSOs) could “help address challenges facing women in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.” Its report was released in April 2022.40 However, the government did not release it own plan or strategy as to what it might or could do likewise to “help address challenges facing women in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.” There has been no formal response to the premier’s council report. The 2020 Alberta Recovery Plan41 was roundly criticized for its singular focus on male-dominated industries and corporate tax cuts as well as its neglect of hard-hit female majority sectors, including care.42

These differences in the application of a gender lens across Canadian jurisdictions is consistent with experiences across OECD countries. A 2020 survey of member countries found that efforts to apply a gender lens to “emergency and exit responses” were “uneven.” Only 11 of the 26 countries surveyed (less than half) reported that they explicitly used assessments of the different impacts of policies on men and women to inform the design and/or delivery of pandemic policy responses and measures.43 Similarly, the inclusion of gender equality in the European Union’s financial program to support pandemic recovery in EU countries, Recovery and Resiliency Facility (RRF), fell far short of expectations. Despite policy guidance and a performance framework, most plans submitted for RRF funding failed to include any “dedicated reforms or investments explicitly addressing gender-related challenges or indicating women as specific beneficiaries.”44 The narrow focus of priority policy areas in the RRF program itself (e.g., green economy; digital economy), as well as the measures selected to monitor pandemic impacts on women, also worked to undermine the program’s potential to advance gender equality.45

The governments that were most successful in applying a gender lens to their pandemic responses were those able to rely on well-established “gender mainstreaming” structures and processes.46 In particular, the OECD noted the pivotal role played by well-resourced central gender equality agencies and the inclusion of women in senior decision-making roles to help “push gender perspectives and the needs of women and girls to the forefront.”47 By contrast, poorly resourced, marginalized gender equality agencies and the absence of readily available disaggregated data were identified as key challenges by a majority of OECD respondents in their use of gender impact assessment tools as part of government pandemic planning. One in five countries (22%) stated the gender issues were simply not a priority for their governments.48

There is an ongoing debate with respect to the usefulness of “gender mainstreaming” initiatives or gender budgeting activism as strategies for transformative change, both of which walk a fine line between contesting and reinforcing established western economic epistemologies and socio-economic disparities.49 The experience of the pandemic—here in Canada and elsewhere—suggests that existing feminist policy architecture helped to shine a light on the gendered impacts of the pandemic through the application of GBA+ in the budget process or the publication of gender action plans. Certainly, access to disaggregated intersectional data was critical as governments and public health agencies scrambled to track real-time impacts.50 But even well-resourced feminist policy agencies and processes were not enough to guarantee a comprehensive, intersectional response of the type that leading feminist organizations, researchers and community advocates were calling for—or, most importantly, to produce the desired results and protections for marginalized women, as the Canadian case study shows.

Feminist recovery programs

Policy statements are important—they signal government priorities. The question is: Did governments follow through and deliver on their early pandemic policy statements? A good deal of the commentary and analysis, to date, has focused on policy prescriptions. We are now in a better position to empirically assess the outcomes of pandemic policies. Were the differences evident in the application of an equity or gender lens to policy also evident in proposed programming? How did the type and scale of gender-sensitive pandemic responses vary across the country? What do the similarities and differences in response tell us about policy drivers for change?

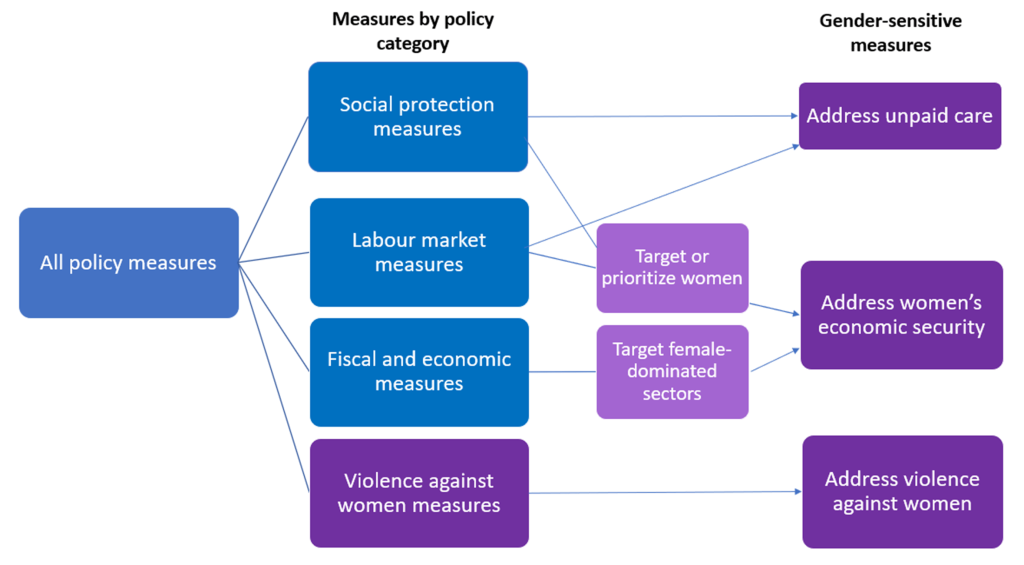

The analysis below explores Canadian pandemic programming, using the UNDP-UN Women’s Global Gender Response Tracker (GGRT) as inspiration and as a guide,57 and a dataset compiled by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives of the 920 policy and programs introduced by federal and provincial governments between March 2020 and June 2021.58 Specifically, it examines the number and type of gender-sensitive (GS) measures introduced—measures that were directed toward addressing in whole or in part gendered risks and challenges caused by the COVID-19 crisis, including violence against women and girls, women’s economic security, and unpaid care work59 (see Appendix 1: Methodology).

Predictably, the jurisdictions that proactively applied a gender and intersectional lens to their pandemic responses and recovery plans had comparatively stronger gendered responses to the pandemic as measured by the number of gender-sensitive programs that were introduced, and the dollars attached to those programs. But there were important differences in the policy mix and policy drivers at play that speak to the challenges that confound feminist policy advocacy in Canada. Below, we look at the federal and provincial responses in turn, highlighting differences and similarities within Canada and between Canada and its country peers.

The federal pandemic response

Through the first waves of the pandemic, the federal government introduced approximately 150 different measures, covering health, income security, loan guarantees for private business, measures to sustain the liquidity of financial markets, and more. The provinces and territories, discussed below, concentrated on coordinating the immense health systems response to the crisis and, in some instances, providing targeted income supports to households, businesses and non-profits, boosting service funding for vulnerable communities (e.g., homeless shelters), providing supports to Indigenous communities and municipalities, and extending protections for renters, workers and selected business sectors.

Together, these programs played a vital role in supporting individuals and households in the face of mass unemployment and the sizable pre-existing gaps in Canada’s health and social safety net. They also shored up employment and sustained economic activity in communities across the country throughout the crisis. Canada stands out from other peer countries in the scale and focus of its COVID-19 response, providing nearly 19 per cent of GDP in total support to keep Canadians and businesses afloat60 and directing an above-average share of funding to households.61 The lion’s share of direct spending—$366 billion of $423 billion, or 86 per cent—came from the federal government.62

Looking at measures that directly impacted households, excluding investments in health, physical infrastructure/housing programs and federal government operations (consistent with the Global Gender Response Tracker methodology), 15 of 79federal programs (19%) met the criteria for being gender-sensitive—including three programs to address the increase in violence against women and girls (Indigenous and non-Indigenous), 11 programs that funded care services such as long-term care and/or provided financial assistance to households undertaking COVID-19 related care (e.g., Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit), and additional funding for the Women Entrepreneurship Strategy.

Another nine programs can also be considered gender-sensitive as they directed significant benefit to women and other marginalized groups. These included two labour market programs that provided training dollars to marginalized groups and those in sectors hardest hit by the pandemic, such as marginalized and racialized women, Indigenous Peoples, persons with disabilities and recent newcomers to Canada.63 Funding for charities and non-profits serving vulnerable people was made available, supporting hundreds of thousands of women and their families and sustaining the work of these organizations and their female-majority workforces,64 which experienced a large drop in their revenues and operational challenges throughout this period.65 Women also directly benefited from the one-off transfer payments to seniors, people with disabilities, families with children, and low-income residents—making up the majority of beneficiaries of these respective groups66 (see Appendix 2 for a list of gender-sensitive federal programs).

Taking these nine programs into account, 24 gender-sensitive programs67 were introduced out of the 79 federal programs providing direct support to households and businesses, that is: 30.4 per cent—representing $42.6 billion (approximately 12%) of total federal pandemic expenditures.68 69 This figure is in line with the UNDP-UN Women global average (32% of the 226 countries surveyed) and the scores of other high-income countries such as the United States (29%) but eight percentage points below top-performing countries Iceland and the Netherlands (both at 38%).

While the size of Canada’s gender-sensitive response (as measured by the number of programs introduced) was similar to that of many other countries, its particular pandemic policy mix stands out. Violence against women (VAW) was the primary focus of gender-sensitive pandemic programming in most regions of the world, including among high-income countries.70 Not so in Canada, where there was a much greater emphasis on addressing women’s economic security and unpaid care needs. Canada’s comparatively smaller emphasis on VAW does not so much reflect a lack of attention on gender-based violence per se, but the broader range of measures introduced here.

Forty-two per cent of the gender-sensitive measures introduced by the federal government addressed women’s economic security needs, including income assistance, as well as supports for emergency community services and provincial and territorial job training efforts in hard-hit sectors of the economy, which was more than twice the share of other high-income countries (15%) (see Table 2). In total, $16.1 billion (38% of federal gender-sensitive spending) was spent on programs that helped women and other marginalized communities cope with the economic fallout of the pandemic.

Of these programs, emergency benefits and targeted one-time payments to individuals and families had the largest price tag ($13.2 billion) and the greatest immediate impact in terms of reach. Recent data from the 2021 census found that nearly three-quarters (74.8%) of women received income from one or more relief programs, while 61.6 per cent of men did so.71 In particular, the one-time payments to seniors, low-income households, people with disabilities and, notably, families with children, directed a large share of their support to women. Likewise, changes to the eligibility rules for Employment Insurance (EI) increased the number of female workers covered. In January 2021, to pick one month, nearly half (48.3%) of the 1.5 million workers receiving regular EI benefits were women, five times the number in January 2020 and an increase of 12 percentage points in their share of recipients over this time.72 This increase reflected both the scale of the economic crisis and the impact of EI rules changes to ensure greater coverage.

Another 46 per cent of federal gender-sensitive measures targeted care needs, more than three times the global average (14%) and one-and-a-half times the average among high-income countries (28%). This included pandemic-related family leave provisions, cash benefits to help compensate parents for reduced working hours or lost earnings due to care responsibilities, and funds to expand and strengthen care services. In total, the federal government allocated $26.4 billion to address care needs, two-thirds of which ($17.8 billion) was directed to women and families via Canada Emergency Response Benefit (March 15-September 26, 2020), the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (available after September 27, 2020) and expanded access to EI special benefits.73

The government also channelled $8.6 billion to bolster care services through several federal-provincial-territorial agreements, including targeted funding to address critical labour shortages and catastrophic service failures in long-term care74 and to stabilize service delivery in the child care sector.75 In addition, an Essential Workers Support Fund was created to boost the incomes of largely female, racialized, low-wage staff working on the frontlines of the pandemic. And in the 2021 budget, the government announced its intention to finance the creation of “a high-quality, affordable and accessible early learning and child care system across Canada” with a historically significant investment of $30 billion over five years76—part of a plan, according to Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, for “making life more affordable for young families, creating jobs, increasing women’s participation in the workforce and giving every child the best possible start in life—no matter where they live.”77

Finally, 12.5 per cent of gender-sensitive measures addressed violence against women (VAW), including programs for Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities, totally $131 million (or 0.3% of federal gender-sensitive spending) in our period of study. Emergency funds were vital to GBV organizations responding to the rise in the incidence and severity of violence associated with the pandemic—experienced most acutely by Indigenous women, women with disabilities, rural women and newcomers. Many organizations and shelters would not have been able to keep their doors open or reorient their programming without emergency aid.78 Additional funds were announced in the 2021 and 2022 budgets in support new gender-based violence (GBV) programming over five years to help “accelerate” work on a National Action Plan against Gender-Based Violence and in response to the Calls for Justice presented in the 2019 Final Report of the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls.79 80

Federally funded VAW programs (and a few provincially funded initiatives, as we see below), made up a much smaller share of pandemic programming in Canada compared to other countries. One hundred and sixty-three of the 226 countries reviewed in the Global Gender Response Tracker introduced a total of 856 VAW measures—making up over half (53%) of all gender-sensitive programming documented globally. Feminist movements and organizations quickly raised the alarm about the growing incidence of violence against women, harnessing established networks to demand action.81

Federal investments in GBV programs made a difference. At the same time, there were significant gaps in the response, reflecting both a lack in preparedness and coordination, as well as the fragile state of pre-existing services. The pandemic required a holistic, coordinated, community-driven response to protect women and gender-diverse people against a predictable rise in violence—as documented time and again in emergency situations.82 In Canada, a momentary reduction in non-intimate partner violence against women in 2020 was offset by the concurrent rise in intimate partner violence. Indeed, overall levels of violence against women surged again in 2021, surpassing 2019 levels.83 Marginalized women remain at greatest risk of violence, especially Indigenous women, women with disabilities and gender-diverse individuals.84 A comprehensive, cross-jurisdictional, and intersectional plan is needed to permanently reverse rising levels of violence and to ensure that women can live free from violence, wherever they live. Communities are still waiting such a plan.85

Provincial governments

Most pandemic assessments have tended to understandably focus on the actions of the federal government, which shouldered the largest share of pandemic costs. But to fully understand and assess the scale and scope of Canada’s efforts, it is also essential to look at the interventions of subnational governments. Over our 2020–21 study period, Canada’s 10 provincial governments introduced over 700 programs across a range of policy areas, from health to employment standards. In many instances, they participated in federal-provincial cost-sharing agreements, and in others, they created their own programs. In total, net provincial contributions represented 14 per cent ($57.5 billion) of total direct pandemic expenditures ($423 billion) over three fiscal years.86

For our analysis, we look at a subset of 465 provincial programs extending direct support to individuals and businesses, again following the Global Gender Response Tracker methodology that excludes expenditures for vaccinations and health services, as well as infrastructure, housing and government operations. We have adopted a broad approach for the designation of gender-sensitive programs, including all long-term care programs and measures explicitly targeted to marginalized communities. We have also included all programming designed to bolster the wages and working conditions of care workers.

In total, 145 provincial measures were identified as gender-sensitive, representing 31.2 per cent of all pandemic initiatives, roughly the same share of GS programming posted by federal government (see Appendix 3 for a list of gender-sensitive provincial measures). Net provincial spending (excluding federal transfers) totalled $13.6 billion—one-quarter of combined federal and provincial spending ($57.5 billion)—on gender-sensitive programs.87 The scale and strength of the different provincial gender-sensitive policy responses, however, widely varied.

As noted earlier, Quebec, distantly trailed by Ontario, British Columbia and New Brunswick, had the largest number of mentions of “gender” in their budget documentation and recovery plans. Quebec also introduced the largest number of gender-sensitive measures, at 30, followed by British Columbia (28), and Ontario (26). Both Nova Scotia and Manitoba introduced 11 GS programs. The remaining five provinces posted the weakest gender responses, with less than 10 measures each, the majority of which were funded through three key federal-provincial agreements to boost the wages of essential workers and to enhance child care and long-term care services.

Looking at province-specific measure density, New Brunswick reported the largest share of gender-sensitive measures, at 47 per cent, followed by Nova Scotia, Quebec and British Columbia (at 37%, 36% and 35%, respectively). Alberta ranked the lowest, at 14 per cent—two times less than the provincial benchmark. In looking at measure density, it is important to note that the total number of programs introduced ranged between a high of about 150 programs in Ontario, followed closely by British Columbia and Quebec, to less than 40 programs in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan. The gender-sensitivity of the pandemic response needs to be understood in relation to the scale of the overall response itself.

As Table 3 shows, the number of programs did not always align with the scale of resourcing. Provinces, on average, spent $357 per person on gender-sensitive measures compared to $1,155 per person by the federal government. Eight of the 10 provinces, however, fell below this benchmark. Indeed, six of the 10 provinces delivered a very weak response. The level of net provincial spending devoted to gender-sensitive programs ranged from a very low $50 per capita in Alberta to a high of $844 per capita in British Columbia, which was more than twice the provincial average.

The expenditure data reveal three groups of provinces: low-spending provinces, including the Atlantic region and Saskatchewan and Alberta; a middle group, including Quebec, Manitoba and Ontario; and British Columbia. British Columbia made the most significant investment in gender-sensitive programs, contributing 43 per cent of all GS funds spent in the province, followed by Quebec, at 27 per cent, and Manitoba and Ontario, both at 22 per cent. Gender-sensitive programs represented a much smaller fraction of net provincial pandemic spending in all of the lowest spending provinces, as shown in Figure 1. These figures provide an important reality check. The number and type of programming, as discussed below, is important to assessing the character and potential impact of gender-sensitive programming. But budgets are critical too. These differences speak to the significant variation and limitations in Canada’s gendered pandemic response.

As a group, provinces were much more likely than the federal government and other high-income countries to invest in economic security measures than in programs that addressed unpaid care needs or gender-based violence. An average of 59 per cent of provincial GS programs targeted economic security needs, in the form of income assistance (e.g., B.C.’s Emergency Response Benefit for Workers, Temporary Rental Supplement), labour market programs (e.g., Quebec’s Programme actions concertées pour le maintien en emploi) or supports for business and non-profit organizations in hard-hit sectors (e.g., Ontario’s Social Services Relief Fund). This was a larger proportion than the federal government’s 42 per cent investment and it was significantly larger than the average for high-income countries (15%).

Three provinces, however, accounted for over 60 per cent of the 85 gender-sensitive economic security measures introduced, led by British Columbia (20 measures), Quebec (17 measures) and Ontario (15 measures). And of these three, British Columbia and Quebec stand out for introducing several income security measures targeting low-income individuals and renters. B.C. spent over $2 billion on income security alone. It was the only province to temporarily increase monthly support to people on social assistance, one of the poorest groups in Canada yet widely ignored in the emergency responses at both levels of government.88 (After considerable community pressure, British Columbia subsequently introduced a permanent boost to welfare rates in April 2021). Prince Edward Island also moved quickly to introduce several small programs for its residents such as a bridging program for self-employed workers in March 2020.89

Another 39 per cent of provincial GS measures were designed to address care needs via “cash for care” programs, investments in care services (including essential worker wage top-ups) and changes to employment standards facilitating COVID-19-related leave. Quebec was the most active, with the introduction of 11 new programs of the 56 care measures reported. Quebec, for example, launched its own wage top-up program before the federal government’s funding was announced in April 2020.90 Another five provinces established “cash for care” programs, including Ontario (with three programs totalling almost $1 billion), P.E.I., Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. In Alberta, for example, the government provided a one-time payment to families with incomes of $100,000 or less to help offset child care costs between April and December 2020.

Some care initiatives under the health care banner in British Columbia should be noted as extending important protections to residents and the largely female, racialized work force in long-term care facilities. B.C. quickly moved in April 2020 to contain the spread of COVID-19 by issuing single-site orders in the long-term care sector. Low wages and the prevalence of part-time work have meant that workers must piece together their income by working at different sites and for different agencies. These conditions led to the rapid spread of COVID-19 among highly vulnerable residents in long-term care homes—and the staff providing care. British Columbia required that all long-term care workers work only at one site, levelling up wages for all workers to the higher public sector collective agreement rates and bringing back many contracted-out support services in house. These steps resulted in large gains for vulnerable female workers and set the bar for the rest of the country. While the single site orders have since been rescinded (as of December 2022), the province has continued to fund the temporary wage increases through standardized contracts between health authorities and employers as part of their Health Human Resources Strategy.91

Gender-based violence programs comprised the smallest category of provincial GS measures—just three per cent of the programs introduced. A majority of provinces did not introduce any pandemic-specific programming at all, relying on the federal programs to flow emergency support to shelters and other anti-violence programs. Quebec introduced two GBV programs and was involved in distributing federal financial support to Quebec-based shelters and community services. In Ontario and Alberta, the governments provided assistance to emergency shelters as part of a community relief package for residential service providers. British Columbia provided a one-month wage top-up to workers in transition houses and support for overflow hotel accommodation.92

Table 5 provides another snapshot on the diversity of provincial program responses in support of anti-violence organizations in the early days of the pandemic. Only half of the 12 provinces and territories surveyed declared women’s shelters and transition houses an essential service. Most governments did not prioritize shelters for receipt of PPE, priority COVID-19 testing or improvements to ventilation. In only five provinces did the premier or the government make a public statement during the lockdown about the importance of fleeing violence if homes were not safe, and that shelters were open and ready to offer assistance. The range of responses reflects, in part, differences in the severity of the pandemic but also differences in interest and capacity to respond to the increase in intimate partner violence that was occurring. It also reflects, more broadly, the differences in interest and capacity in addressing the gendered impacts and systemic inequities that were exacerbated within the context of the pandemic.

Accounting for policy differences

How do we account for variations in the scope and focus of the different government responses within Canada? What factors enabled or constrained a more effective response from a gender perspective?

A recent UNDP-UN Women study of the pandemic responses across the world explores several potential policy drivers of interest here.93 Their key take away was that when the crisis hit, governments turned to what was there, scaling up the tools at their disposal, more often than not sacrificing consultation and engagement with community in the quest for speed. Within this context, “[w]hether and how gender-specific risks and vulnerabilities [were] addressed [depended] to a large degree on how well [spaces for gender mainstreaming] were integrated into pre-existing policies and institutions.”94 Countries with poorly developed feminist policy capacity—or where it was absent altogether—had the weakest gender responses, even after taking into account national income and the severity of the pandemic. Similarly, countries that had invested in universal social protection systems and labour market institutions—including care infrastructure—were better able to respond to the shock. In short, gendered pandemic responses were “heavily path-dependent.”95

Institutional factors such as these were important in the Canadian context as well. Jurisdictions with more developed feminist policy architectureandgreater state-community engagementalso delivered stronger gender-responsive programming in reaction to the crisis, as articulated in their recovery plans and the number of programs introduced. On this score, the federal government and the province of Quebec stood out. The resources and staffing available to Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) Canada and, to a much lesser extent, the Secrétariat à la condition feminine were considerably larger than those available to their other provincial and territorial counterparts. These governments were able to rely on established policy and budgeting processes to highlight and respond to the gendered impacts of the pandemic. They were also able to quickly deliver much-needed financial support to communities, leveraging established relationships with women’s sector organizations and, in the case of Quebec, the presence of long-standing provincial and regional feminist service and advocacy networks. In Saskatchewan, by contrast, there was effectively no gender response from the government or its tiny Status of Women Office.

Women’s representation in parliament was another key policy driver identified in the UNDP-UN Women study. Countries with higher levels of women’s representation adopted 4.5 times more gender-sensitive measures compared with those with lower levels of women’s representation.96 Here in Canada, Quebec and British Columbia ranked first and second with respect to their share of female legislators in 2020 and with respect to the number of gender-sensitive programs introduced. Alberta, with a below-average share of female legislators and an even lower share of female cabinet members (27%), introduced only six gender-sensitive programs (see Table 6). The top decision-making bodies in British Columbia and Quebec were gender-balanced at the time, or close to it in the case of Quebec (at 46%). Female leaders like Finance Minister Carole James in British Columbia (since retired) played a key role in developing their provincial pandemic responses to ensure they were attuned to the differential impacts of the pandemic.97

At the same time, women’s representation in the federal parliament was only 29 per cent in 202098—placing Canada at 59th in 2020 in international rankings.99 There was strong female representation on pandemic decision-making bodies, including around the cabinet table, but Canada has struggled to make substantive gains in women’s representation in the House of Commons.100 Other policy drivers, in addition to established feminist policy capacity, were clearly at play in shaping the federal (and provincial) responses to the pandemic—including the level of parliamentary support,101 political orientation of the governing party, and available financial resources. With regard to the former, the federal Liberal party returned to government after the 2019 election as a minority government with only 157 of the available 338 seats. It required the support of other partners, notably the New Democratic Party, to pass its pandemic agenda in the face of opposition from the Conservative Party and Bloc Québécois. Liberal-NDP cooperation has been instrumental in moving gender-sensitive pandemic programming forward.102

The federal case also highlights the importance ofthe political orientation of government with respect to pandemic management and recovery planning. There were notable differences between the approaches of right-of-centre governments, such as Alberta and Saskatchewan, and progressive-centre governments, such as British Columbia.103 In Alberta, for example, the government was reluctant to introduce restrictions following the initial period of lockdowns in 2020. Instead, it emphasized an alternative strategy of personal responsibility and accountability. It was the first province to fully lift restrictions (on July 1, 2021), with its premier declaring that Alberta was “open for summer”, only to reintroduce restrictions in September as surging cases placed an untenable strain on hospitals.104 By contrast, the scope and scale of British Columbia’s pandemic aid package, under the leadership of the New Democratic Party, was larger and more broadly oriented around investments in health and safety, supports to people and businesses, and preparing the province for “a more sustainable, inclusive and equitable future.”105 This was consistent with its 2020 electoral platform, its 2021 budget and with NDP beliefs in the positive role of the state as a tool for progressive change.106

The impact of political orientation was also evident in the different provincial approaches to the care crisis. Some provinces prioritized public investment in the care economy (e.g., B.C.’s investment in child care) while others extended support directly to families (e.g., Ontario and Alberta)—a “cash for care” strategy reflective of a private responsibility, “hands off” approach to social policy, often designed to reward the “traditional” nuclear family,107 and historic resistance to feminist claims for gender equality.108 In Manitoba, the Progressive Conservative government dedicated modest funds to expanding child care spaces for under-served families, but handed the funds over to the Manitoba and Winnipeg chambers of commerce to distribute, with the goal of expanding for-profit services.109

Quebec’s right-of-centre government, by contrast, made important investments in care services—to public, non-profit and for-profit providers—as part of its pandemic response, for instance, supplementing federal transfers for essential worker wage top-ups. Those investments set Quebec apart from the policies of other right-of-centre conservative parties, but it was in keeping with Quebec’s long tradition of state activism dating back to the 1960s and 1970s.110

Last, but certainly not least, national incomewas an important factor shaping and constraining gender-sensitive responses to the pandemic. Globally, high-income and middle-income countries were more likely to introduce stronger and more holistic gender-sensitive responses compared to low-income countries.111 Likewise in Canada, it was the federal government that stepped forward to finance the bulk of Canada’s pandemic response, drawing on its considerable financial resources and spending powers to do so. Its gender response was certainly the largest—as measured in direct spending and the millions of people impacted. Over the period of study, total federal pandemic spending represented 16.4 per cent of Canada’s GDP—the equivalent of $9,618 per capita. It spent $1,513 per capita, approximately 16 per cent, on gender-sensitive transfers and services.

Wealthier provinces also had more bandwidth than lower-income provinces to respond to the pandemic and its gendered impacts. But it was British Columbia (the 5th wealthiest province in Canada), followed by Quebec (the 6th wealthiest) and Manitoba (the 7th wealthiest) that announced the largest pandemic packages of the 10 provinces (at 3.4%, 3.4% and 3.3%, respectively). Alberta, the wealthiest province in Canada, spent only 1.2 per cent of its GDP on its pandemic response—despite experiencing comparatively high levels of COVID-19 illness and death throughout late 2020 and 2021. Likewise, Ontario and Saskatchewan delivered anemic pandemic responses given the scale of the challenge and the resources at their disposal.

Figure 3 presents these same calculations but looking at the net provincial investment in gender-sensitive programs by province. We see a similar pattern. British Columbia devoted 1.5 per cent of GDP to gender-sensitive programs, distantly followed by Quebec (0.8% of GDP), and very distantly followed by Newfoundland and Labrador, Saskatchewan and Alberta (at 0.1% of GDP). Most provinces sat back and let the federal government do the heavy lifting, focusing their efforts on health care and support for businesses,112 giving only a cursory nod to programming to address the pandemic’s disproportionate impacts on women and other marginalized communities.

As David Macdonald shows in Picking up the Tab, the provincial pandemic response was largely underwritten through a series of federal-provincial-territorial funding agreements, tied to policy goals such as the safe reopening of schools, mass vaccination programs, and the provision of emergency housing. In total, the federal government directed $29 billion to the provinces in support of provincially delivered programming. This funding played a crucial role in supporting the pandemic response, particularly for smaller and historically poorer provinces, as might be expected. For example, the federal government picked up 98 per cent of COVID-19 expenditures in Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick compared to 84 per cent in Quebec.

As importantly, federal funding also facilitated the introduction and character of the pandemic response, making available support for several key policy priorities crucial to women’s well-being. Roughly two-thirds (63%) of the gender-sensitive programming that was introduced was fully or partially offset by federal emergency funding. The figure was even higher with respect to care services and other programs: 89 per cent. Had these financial transfers not been available or tied to specific goals, such as the provision of child care or services for vulnerable populations, the number of provincial programs qualifying as gender-sensitive would have been considerably smaller (indeed, potentially non-existent), exacerbating the negative impacts of the pandemic on the women and marginalized communities.

The provision of wage top-ups for essential workers is the most notable example. In mid-April, as deaths mounted in long-term care homes, the federal government announced its intention to create a program to support low-wage essential workers who were working in very difficult circumstances at great personal risk.113 Federal funds were made available to provinces and territories on a cost-shared basis (75% federal, 25% province) to provide wage top-ups to largely female and racialized frontline workers. The record shows, however, that, in many instances, provinces were reluctant to apply for federal funding, even on the most advantageous terms. Alberta waited nine months before confirming its application, in the face of mounting public pressure.114 By the spring of 2021, all 10 provinces had applied for federal funding, but five out of 10 provinces chose to leave federal money for essential workers on the table. Saskatchewan, for example, matched only 5.2 per cent of its available funding and chose not to access almost $50 million in additional support, neglecting the opportunity to invest in Saskatchewan’s majority female care workforce.115

This example speaks both to the importance of the transfers setting the policy agenda and notable gaps and tensions characterizing Canada’s overall response to the gendered impacts of the pandemic.

Overview

Policy hits and misses

Our analysis shows that governments in Canada mobilized a large response to the COVID-19 pandemic, developing and implementing a variety of policies and programs to assist individuals and the broader society navigate many of the negative impacts of the crisis. The proportion of these measures that directly or indirectly addressed gendered risks and challenges caused by the pandemic was just shy of the global average—both for the federal government and for the provinces collectively. But Canada’s response had greater breadth than many other countries, focusing to a larger extent on women’s unpaid care needs and threats to the women’s economic security, especially among low-income households.

The federal government, for its part, used its considerable spending power to support business and individual households, contributing to Canada’s economic recovery. Federal pandemic transfers, for instance, more than offset what would have been a steep rise in poverty116 and expanded eligibility (at least temporarily) to those providing essential care and schooling to those in need, including children, vulnerable seniors and those living with illness or disabilities. The federal government also underwrote 71 per cent of the $65 billion spent on pandemic-related health care responses, including the cost of testing, contact tracing and vaccination programs. Sizable new investments in child care announced in 2021 hold out the promise of finally creating a Canada-wide system of early learning and child care that is affordable, inclusive and accessible—and essential for the advance of gender equality in Canada.

The provincial contribution to the pandemic was much smaller by orders of magnitude but, like the federal government, roughly 30 per cent of all measures introduced to combat the pandemic responded to the challenges facing women. Overall, Quebec had the strongest gender response, as measured by the number and breadth of GS measures, while Alberta and Saskatchewan had the weakest, despite the relative severity of the pandemic in each of these jurisdictions and available provincial resources (as shown in Figure 2). But it was British Columbia that led the group in terms of investment, spending $844 per capita on gender sensitive measures (43% of all GS spending in the province)—17 times the amount spent by Alberta (at $50 per capita), Canada’s wealthiest province.

The provincial policy mix varied as well. Some provinces—typically those with the larger number of gender-sensitive responses—focused their efforts on economic security. By contrast, federally funded care initiatives made up the largest share of the policy mix in provinces with weaker gender responses. This is not a surprising finding. The availability of federal funding was a key policy driver, as noted earlier, especially in provinces where the gendered impacts of the pandemic were not top of mind. Had it not been for federal support, the health and community service response to the pandemic would have been considerably weaker, coming on the heels of provincial austerity programs in many instances.

There were other individual programming differences too. Quebec expanded labour market programming to assist workers who were struggling with recurring closures. British Columbia and Ontario mounted Indigenous-specific programs while several municipalities worked with marginalized communities to target vaccination efforts and other public health supports.117 Several provinces took action to keep child care centres open in March 2020 and coordinated child care provision for essential care workers.118 Newfoundland and Labrador created a Students Supporting Communities program, which supported student outreach to vulnerable residents experiencing social isolation.119 Most provinces left the responsibility of financially responding to the tragic rise in violence against women to the federal government.

At the same time, there were significant policy gaps that neither provincial nor federal programming addressed. While Canada’s gender response to the pandemic may have been comparable to those of many other high-income countries, it still fell short of adequately responding to the breadth and scale of the pandemic’s social and economic fallout, as documented by groups such as the Disability Justice Network of Ontario, the Caregivers Action Centre, and the Yellowhead Institute, all reporting on the lived experiences of the marginalized.120

Rapid research, community surveys and commentary from community-based organizations and advocates have played a crucial role in exposing the disconnect between the stated goals of programming and community experiences on the ground. As Julia Smith and her colleagues note in their study of British Columbia residents who were negatively impacted by the pandemic, the focus on lived experiences demonstrates “the need to move beyond a focus on policy trackers which, while a necessary step, only indicate if gendered risks and challenges have been considered, not why and how gender is included, and whether inequities are meaningfully addressed.”121

Most pandemic-related cash transfers, for instance, were short lived and, by design, excluded many marginalized women, such as migrant and undocumented workers who worked on the frontlines of the crisis122 and sex workers who did not qualify for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) or other income supports.123 Women on social assistance, who are among the poorest of the poor in Canada, were left to struggle on incomes substantially below the poverty line in all provinces and territories124—more than 1.7 million individuals and families (11% of all households) in 2020.125 In the absence of mandated paid sick leave, low-income workers chose work over health and safety because they couldn’t afford to do otherwise.126 Most provinces steadfastly refused to introduce these protections. Hundreds of thousands of workers were left to nurse illnesses with no financial support and many are now being rejected by workers’ compensation programs.127

The response to the crisis in care, and its disproportionate impact on women, was hit and miss as well.Initial federal funding to address the crisis in child care was one-quarter of the $2.5 billion that advocates were calling for to stabilize revenues, curb staff losses and enhance service delivery to meet new safety standards for children and staff.128 Provincial policy choices in key areas such as funding, eligibility, and requirements also made “a considerable difference in how childcare fared.”129 Prince Edward Island and Nova Scotia, on the one hand, provided centres with their usual funding as well as covering lost parent fee revenue, while Alberta extended only limited support to help navigate the steep decline in income and was reluctant to take up the emergency child care funding on offer by the federal government.130 Likewise, provinces extended varying levels of support to other community service providers—employment programs, gender-based violence services, attendant care, housing support and legal aid—which were all struggling with similar pandemic-related pressures.131 These pressures have become more acute, with many care workers now leaving their jobs, ground down by the lack of recognition, low pay and poor working conditions.132 Making matters worse, it appears some provinces are poised to usher in a new wave of privatization.133

The pandemic graphically revealed the ways in which Canada’s economy and care work are fundamentally intertwined and the critical role that the social safety net plays, or fails to play, in times of crisis. The scope and scale of the government response to the care crisis was wholly inadequate to the task, as millions of women stepped forward to take on the expanded care and educational needs of their families in the face recurring public health shuts downs. Many not only lost income, they also struggled to access necessities and needed family and community supports.134 Marginalized women faced the greatest barriers, including women with disabilities, lone-parent mothers and precarious workers.135 Governments effectively “downloaded care responsibilities on to women without corresponding recognition or support.”136

Canada’s overall pandemic response identified and responded to some of the critical challenges facing women and marginalized communities as a result of the pandemic through the application of a gendered (and sometimes intersectional) lens.137 But while the Canadian pandemic response was “gender aware”—it failed to get at the structural factors at the root of gender inequality, such as the gendered division of labour, the lack of employment protections for low wage workers, or exploitative immigration policies.

Most pandemic programs have now run their course. With the notable exception of new investments in child care and pending, but unspecified, federal reform of EI and disability benefits, provincial and federal social and economic programs continue to respond poorly—as they did in the past—to the systemic barriers that women face, today in a new context of heightened economic uncertainty and rising living costs.

Leveraging lessons from the pandemic to advance gender equality

The pandemic continues to be a moving target and much of the evidence regarding the impact of pandemic programming is still emerging. There is a good deal yet to learn about the pandemic strategies that worked, in whole or in part, to address diverse women’s needs and the factors associated with these successes. Certainly, much more remains to be done to document and analyze the role of national and local feminist organizing, including their role in shaping government responses and sustaining community. “The challenge going forward,” the UNDP-UN Women study concludes, “will be to create the conditions for policy innovations to stick and translate into lasting change, while also building on tried and tested solutions that worked for women during the pandemic to lay the foundations for a more sustainable, resilient and gender-just future.”138

This study offers insight into Canada’s varied response to the gendered impacts of the pandemic, both its strengths and its weaknesses. Below are six take-aways for systemic change moving forward.

1. Strengthening foundational income supports as well as introducing targeted programs was essential in delivering needed financial aid to millions of women struggling with employment and income losses.

There is no question that federal emergency and recovery benefits, in combination with the one-time transfers, delivered substantial financial assistance to low- and modest-income households and prevented a devastating rise in poverty. One study early in the pandemic found that without government transfers, most financially vulnerable families would not have had the resources to make ends meet for even one month of joblessness. This was the case for over half of all single mothers (56.3%), roughly half of Indigenous households living off reserve (46.9%) and households headed by a recent immigrant (49.7%).139 For the large majority of women, pandemic benefits made a huge difference to their total income in 2020.140 The upshot: Canada experienced a sizable decline in poverty between 2019 and 2020, from 16.4 per cent to 13.3 per cent (to 12.5% among men and 14.1% among women).141

These interventions offer important lessons for permanently strengthening income security. One important feature of the Canada Emergency Response Benefit was its emphasis on low-wage workers earning up to $1,000 per month. Given women’s over-representation among low-wage earners, income security programs that target precarious workers and offer a minimum benefit threshold hold the greatest promise for women’s enhanced economic security. CERB’s program design effectively captured a large group of female and racialized workers in the low-wage labour force, juggling work, care, their own health and life. This group would not have qualified for EI and would not have qualified for $2,000 per month in benefits. Likewise, expanded coverage for self-employed workers extended vital support to low-wage female workers in sectors like food and accommodation and personal services. Other countries went further by providing support for informal workers.142

As it is currently designed, the Canada Workers Benefit does not provide much of a bulwark against poverty.143 And it does not extend support to the many who must rely on precarious, irregular, or unstable work. The CCPA’s Alternative Federal Budget 2023 contains two new proposals to help fill this glaring gap in our safety net: a new Canada Livable Income benefit for adults aged 18 to 62 who do not have children and a proposed design for the new Canada Disability Benefit.144 These two programs, along with expanded eligibility and a new income floor for Employment Insurance (both regular and special benefits), would go a considerable way to providing an assured income guarantee for all working-age adults and especially low-wage women.

2. The federal government explicitly directed support to caregivers through different pandemic programs, acknowledging this vital work and the impact of the unequal burden of care on women.

Another critical feature of the federal government’s plan was a more expansive approach to providing income support to parents and caregivers than previously available. The loss of child care is recognized under the current Employment Insurance program as a legitimate reason for job separation, but there are significant barriers to claiming benefits.145 Providing ready access to income replacement in the face of recurrent shutdowns of child care and public education via CERB and its successor programs (CRB, CRSB and CRCB)146 was an important, albeit temporary, improvement to the policy. These programs, in combination with targeted supports for families, such as the top-ups to the Canada Child Benefit, and selected provincial benefits, such as B.C.’s enhancement of social assistance,147 boosted women’s economic security and assisted with the gendered increase in unpaid care work.

These benefits were also directed to individual workers and were not, unlike many other federal benefits, subjected to a family income test. There was an income test attached to the Canada Recovery Benefit, but it was evaluated on an individual basis. This feature ensured that female workers who were impacted by COVID-19 were not excluded from receiving support, particularly women living in couple households where there was a sizeable difference in income between spouses,148 considerably enhancing the effectiveness of these programs. To be sure, these benefits were only available to those who could demonstrate labour force attachment and claimants had to have lost at least 50 per cent of their average weekly income in order to qualify (and 60% under the CRCB). But it threw open the door to doing things differently.

In provinces where families struggled with prolonged lockdowns and school and child care closures in provinces, such as Ontario, these programs made a huge difference.149 We saw this in the disproportionate take up of the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit in Ontario and the western provinces. By contrast, in Quebec, the relative strength of its child care system helped offset the impact of first wave employment losses, facilitating a speedy rebound in employment.150 The CRCB ended in May 2022. Now is the time to take stock and consider systemic reform of the benefits on offer and related existing employment standards to better support caregiving across the life course.151

3. Time-limited investments in the care economy were not enough to stabilize the system, which had been drained and strained by years of austerity. Moving beyond a fragmented approach of underfunding, privatization and exploitation propped up by systemic discrimination must be an investment priority moving forward at both levels of government.

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the many ways in which inequality is baked into our economy and institutions. It revealed the precarity and deadly consequences of our reliance on market-based service in fields like long-term care as well as the negligent and exploitative treatment of care workers, as reflected in their low wages and poor working conditions.152 153 There was a fleeting moment when care workers were held up as heroes—some receiving pay top-ups to recognize their extraordinary effort and to help stem the exodus of workers from service. But these efforts fell far short of the comprehensive and inclusive approach needed. Today, care workers are leaving their jobs in large numbers, overwhelmed and burnt out after three long years of working under acute stress.

The pandemic highlighted care work as an economic and social necessity and a core pillar of the social contract. Countries with strong, publicly funded child care systems, for instance, did not face bankruptcies or layoffs in the child care sector as Canada did.154 Recovery planning provides an opportunity to tackle, head on, the gender bias in economic thinking and public policy that has neglected the value of social infrastructure and exploited women’s paid and unpaid caring labour. The goal should be to ensure that wealth, work and care responsibilities are more fairly distributed, and that everyone—racialized women, women with disabilities, low-income women, gender-diverse people—can engage in the economy on equitable and just terms, in ways that generate shared prosperity and well-being.

Both levels of government have a vital role to play in elevating the quality of employment in the Canada’s care economy through investments in public care infrastructure, sector-specific labour force strategies, and the strengthening of employment standards that guarantee the appropriate valuing of the skill, effort, responsibility, working conditions, and support for equitable, decent working conditions. Federal investments in child care, long-term care and gender-based violence services—announced in the 2021 budget—are important building blocks for creating a stronger care economy and advancing gender equality. Vigilance and additional investments are now needed across the entire range of health and education services, including labour standards and immigration policy, to ensure care for those in need and decent work for those who provide it.155

4. The new early learning and child care deals have shown that federal-provincial transfer programs with clear objectives, conditions and accountability mechanisms can be effective tools for advancing change across the country. We need the same approach to building out essential public infrastructure—starting with new investments in health care and anti-violence programs.

Canada has a long history of government transfer programs that flow funding (via cash and tax room) from the federal government to the provinces and territories to ensure fair and equitable access to public services and supports.156 The Canada Health Transfer and the Canada Social Transfer and Equalization program are the largest, but there have been several other programs targeting specific areas, such as child care, mental health, and employment programs. Funds provided under the CHT, for instance, are subject to the principles set out in the Canada Health Act, but, for the most part, provinces and territorial governments can dispense funding as they see fit—and have done so since 1995, when the federal government unilaterally cut transfers to the provinces and reduced their direction and oversight.157 We have been playing catch up ever since.

The massive disruption in people’s lives occasioned by the pandemic has paved the way for rethinking and rebuilding the status quo. The new early learning and child care deals illustrate, once again, what can be accomplished with an infusion of multi-year federal funding tied to specific goals, measurable outcomes, regular public reporting, and consequences if goals are not met. Pandemic wage top-up programs and training support for personal support workers and child care workers encouraged provincial governments to step up to improve wages and create new recruitment initiatives. As members of the Care Economy Group stated in summer 2022: “We’ve learned over the past year that you can’t buy change unless there’s an explicit agreement about the transformations you’re buying.”158

There is no debate about Canada’s sizable social infrastructure deficit and the imperative to scale up public funding to ensure better access to quality health care, education and training, child care, community services and attendant care, affordable transportation, internet services, and housing—experienced most acutely by marginalized communities. Each sector or area demands its own strategy, reflecting its unique history and degree of private market involvement. But entitlement to quality support could be guaranteed if it was backed up by standard setting and independent monitoring, robust employment protections and regulation, provisions for public management and delivery, and increased funding—even in instances where there is disagreement on policy between the governments involved.

5. The pandemic has reinforced the need to expand the application of an intersectional lens, invest in the production and use of disaggregated data, and build feminist policy capacity both within and outside of the state.

Varying levels of state capacity clearly influenced the speed, breadth and reach of gender-sensitive government responses to the pandemic. The UNDP-UN Women’s analysis found that the strength of women’s policy agencies and the depth of feminist policy capacity were key to engendering the pandemic response. Our survey of women’s policy agency in Canada reveals large differences in capacities between the federal government and the provinces and among the provinces themselves. The federal government and the government of Quebec have gone the furthest in “gender mainstreaming”—establishing processes for applying intersectional lens to policy-making, expanding sources of disaggregated data and information, engaging with organizations committed to gender-justice, and (modestly) investing in those same organizations and the critical community work they do. But there’s a long way to go yet in strengthening and building this vital infrastructure out across the country.