Two years into the global COVID-19 pandemic, Canada’s long-term care homes remain a tragic symbol of neglect: more than 20,000 of the country’s 36,500 COVID-related deaths occurred in long-term care homes—the worst record in the world.

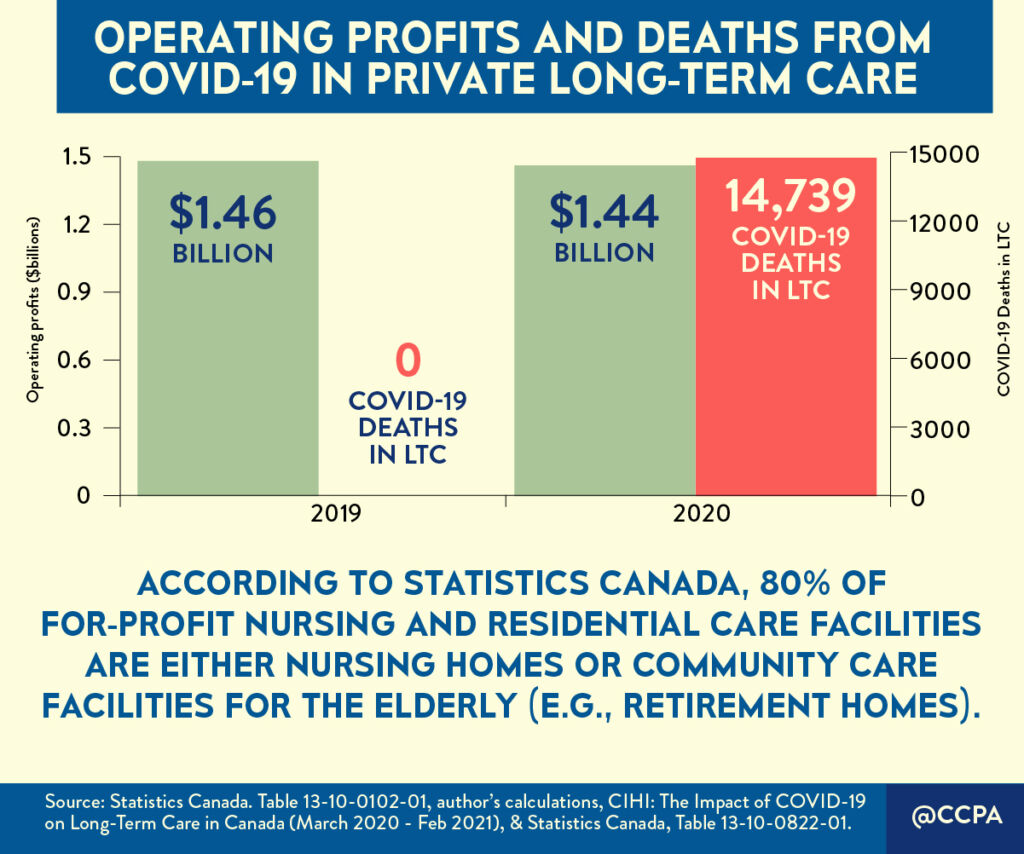

The majority of COVID-19 infection rates and deaths in Canada’s long-term care homes were concentrated in the for-profit sector; a sector owned and operated by major chains that continued to reap profits, despite the tragedy unfolding in those homes.

In 2020 alone, COVID-related deaths in for-profit long-term care homes made up 78% of Ontario long-term care resident deaths compared to non-profit long-term care homes.

We also have a picture on how much private facility operators of for-profit long-term care homes amassed in profits that year, thanks to new data from Statistics Canada on the sector. The amount: $1.4 billion.

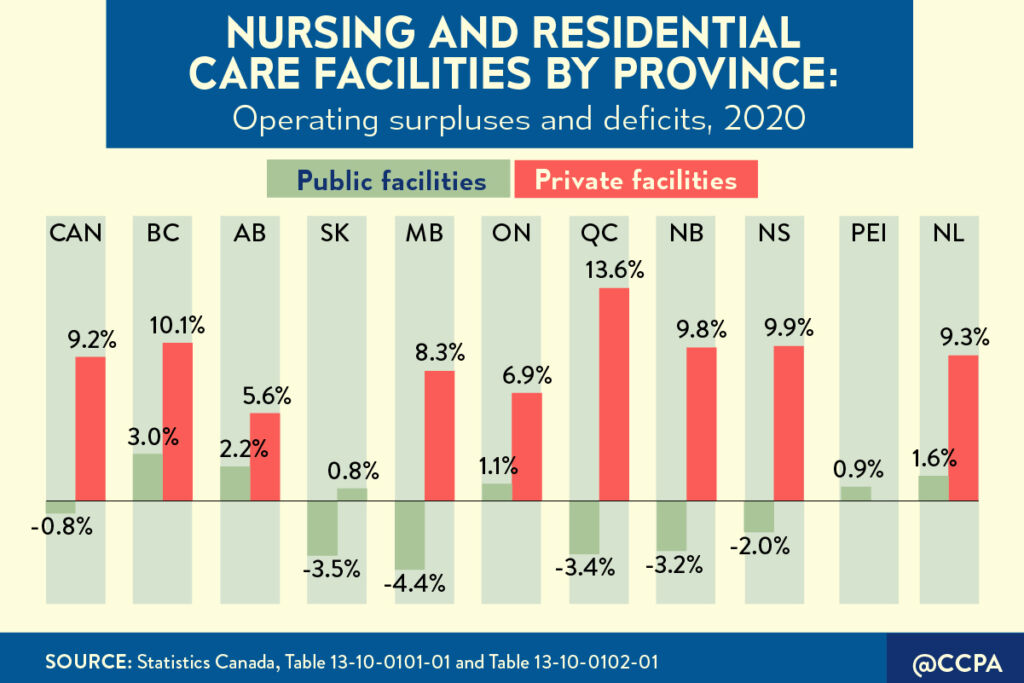

Nursing home profits in 2020 were highest in Quebec and Ontario—provinces with the largest share of the population and the largest share of seniors’ residential facilities—according to StatCan data. Quebec’s nursing homes have been the most profitable for several years. They did not skip a beat in the first year of COVID-19, returning a 13.6% profit to investors in 2020.

Many long-term care operators in Quebec and elsewhere also applied for pandemic funding including the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy (CEWS) and top-ups for essential workers, even as they paid out millions in dividends.

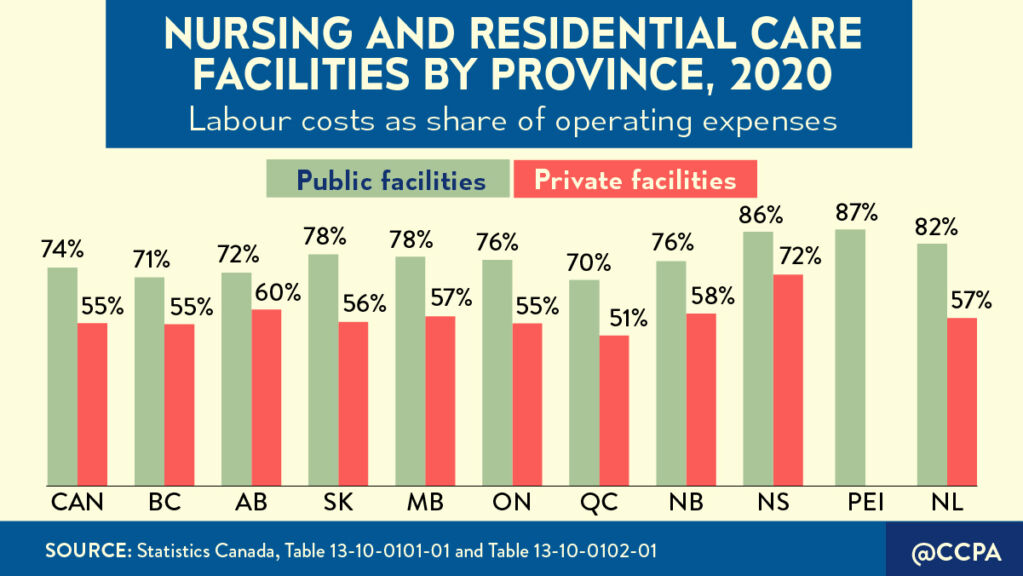

Large private chains, now expanding across Canada, generate sizable profits for their shareholders through short staffing, lower wages, benefits, and pensions. Across Canada, for-profit facilities have 34% fewer staff and spend less on direct care than homes under public ownership.

A recent report by the B.C. Office of the Seniors Advocate found that the for-profit sector spent an average of 17% less per worked hour compared to non-profit facilities. The wages paid to care aides, in particular, were up to 28% less than the industry standard.

A single metric says it all: Labour costs, as a proportion of operating expenses, are considerably lower in for-profit facilities than they are in public facilities. Nationwide, labour costs in for-profit long-term care facilities were 19 percentage points lower, on average, in 2020.

Every dollar siphoned off for profits is one less dollar to support essential care for vulnerable residents.

Canada’s long-term care system was ill-prepared for COVID-19, drained and strained by two decades of austerity measures and neglect. The scale of the disaster in nursing homes should have sparked a fundamental rethink of how we care for seniors and people with disabilities in this country. Instead, we’ve had many earnest statements but little substantive change.

In Ontario, we’ve actually lost ground. For-profit long-term care companies have successfully lobbied to dodge responsibility for the death and suffering that took place in their homes. The government passed legislation to retroactively indemnify homes against all but the most deliberate malpractice, while locking in 30 years’ worth of new business contracts to update old homes and build and operate new ones.

For its part, the federal government is promising new national standards for the sector, enshrined in legislation, along with $3 billion over five years to support improvements in elder care. The provinces want increased federal transfers for health, with no strings-attached, to pursue their own agendas. Both appear set on a collision course.

What will it take to get governments on the same page? The most serious population health crisis in a century? The worst record of COVID-19 long-term care deaths than any wealthy country?

Transforming long-term care must prioritize moving beyond the fragmented approach of underfunding, privatization, and exploitation of care workers, propped up by systemic discrimination. Significant investments in quality public services will lift up these largely female, racialized workers and have a positive cascading impact in the economy, environment and communities.

Similarly, governments must work collaboratively to bring private facilities and services fully into the public system, under a framework of robust national standards of care. This will require substantial investment to expand quality institutional and home care in the public and non-profit sectors. In a country that spends 30% less than average OECD country on long-term care, this investment is long overdue.

Budget season is upon us. It is time to place vulnerable seniors and everyone who relies on social care at the heart of our recovery.