In the early days of the CCPA, Canada’s free trade debate was a galvanizing force.

Our experts joined the movement opposing the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement, on which former U.S. President Ronald Reagan campaigned in 1979.

Negotiations on the deal began in 1986 but reached a fever pitch during the 1988 election, after which re-elected Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney signed the unpopular agreement.

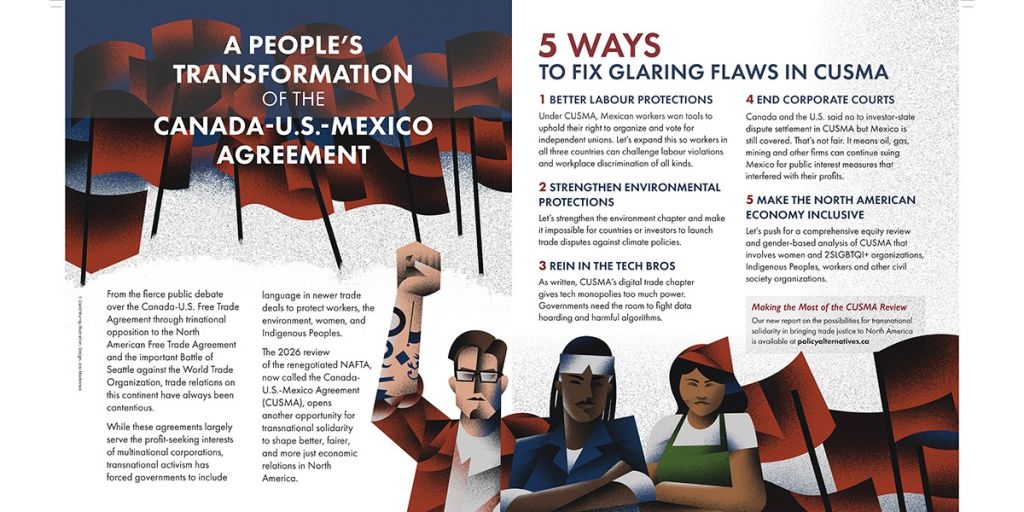

Like many political battles, the road to trade justice can be long and winding. This issue of the Monitor looks at transnational activism around trade agreements in North America, with a focus on Mexico.

From NAFTA—the free trade agreement that replaced the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement—to CUSMA, which replaced NAFTA, NGOs, labour and social justice movements continue to resist neoliberal market ideology.

Tamara Kay’s lead article focuses on the role labour transnationalism played in supporting hard-fought labour reform victories by and for Mexican workers.

“The profundity of the change in the Mexican labour law regime cannot be overstated,” writes Kay.

While CUSMA still tilts the balance in favour of corporations, it’s also been the catalyst for unified action among workers in all three countries.

“NAFTA—the concrete embodiment of globalization in North America—had the unanticipated consequence of catalyzing labour transnationalism, defined as ongoing cooperative and collaborative relationships among Mexican, U.S. and Canadian unions and union federations,” writes Kay.

A new Rapid Response Labour Mechanism in CUSMA was “designed to support constitutional and labour law reforms undertaken by the Mexican government between 2017 and 2019,” Laura Macdonald writes. It’s specific to key facilities, it leads to rapid resolution, and it’s tough: “Harsh sanctions can be levied on companies that fail to remedy proven labour rights violations.”

Like everything, it takes pressure from the ground to ensure new agreements and institutions benefiting workers are adhered to—and to push for more.

In Mexico, Indigenous Peoples have been organizing against the Mayan train, a megaproject putatively aimed at providing easier access to archaeological sites and UNESCO World Heritage destinations.

However, the plan is going ahead without consent from the Mayan people, who are resisting it. In this issue, Laura Primeau writes about how that resistance benefited from transnational connections and international law.

“Organizations … took legal action against the government,” writes Primeau. “They contend that the Mayan train violates Article 4 of the Mexican constitution, which guarantees the right to a healthy environment, as well as rights to clean water and to information, and the rights of Indigenous Peoples established in international human rights treaties ratified by Mexico and also protected by the constitution.

“Their message was clear: in a commonly used phrase among activists, the Mayan train is “not just a train, and it is certainly not Mayan.” It is a mega project that reorganizes Mayan territories in the name of ‘national development’.”

In a similar story of collective resistance, Eduardo Mendoza writes about activism in San Diego and Tijuana—border cities that: “have become a lightning rod for political debates about migration in both the United States and Mexico. The politicization of migration issues, which escalated in the Trump era, has placed extreme pressures on these cities and on the migrants themselves, who are exposed to diverse risks and vulnerabilities.”

Mendoza interviewed NGOs that help migrants in both cities, and writes about their role in “shaping the socio-political landscape and fostering cross-border solidarity and resilience.”

In a Q&A with Carlos Heredia, the influential Mexican civil society activist and academic who fought NAFTA reinforces the importance of building “joint answers” to the challenges we face: “Over time, what we concluded was that it was not trade measures that were at heart being negotiated. … A national project was being negotiated. A social pact, indeed.”

This issue of the Monitor is a reminder that, in the two years leading up to the next CUSMA review, people have the power to reshape trade agreements so they work in the public interest. When the resistance goes transnational, wins are possible.