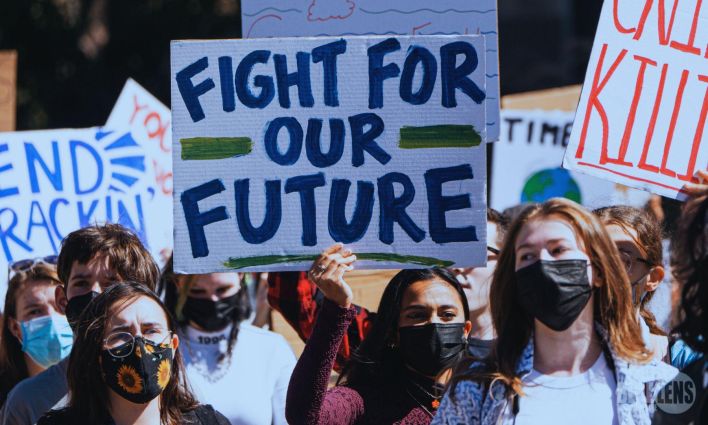

The anti-racist uprising that occurred in 2020 brought a greater understanding of how white supremacy and settler colonialism are interwoven into Canada’s history, and how they remain embedded as systemic racism today. It also brought closer attention to the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States.

That was the context that brought us together as we worked on the 2021 publication Challenging Racist “British Columbia”: 150 Years and Counting, as author and reviewer. We began a conversation after one review of the booklet asked how “racial capitalism might be deployed as a conceptual prism to reveal the intersections of race and class, as well as the maintenance of imperial control of global and local economies through the expropriation of land and exploitation of natural/human resources?”

This quickly led to the work of Cedric J. Robinson, who published Black Marxism: The Making of the Black Radical Tradition in 1983. Reissued twice since then, Robinson’s work provides a theoretical underpinning for the notion of “racial capitalism”.

Black Marxism probes the origins of race and racism. Robinson wrote that the notion of ‘race’ originated in Europe and preceded capitalism, later becoming foundational as the European capitalist class gained power. The second part of Robinson’s study focuses on Black radicalism, challenging traditional Marxist views of slavery as a form of primitive capitalist accumulation and, according to Robinson, the “preoccupation of Marxism with the industrial and manufacturing centers of capitalism.”

Theories of revolution mistakenly focused on the European proletariat instead of what Robinson believed was a “more complex capitalist world system” in which other forces, particularly the Black radical tradition in the African diaspora and Africa itself, were extremely important. Robinson concludes his study by recalling the lives of three individuals who made major contributions to the articulation of Black radicalism: W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Richard Nathaniel Wright.

Black Marxism provided a theoretical foundation for the notion that capital accumulation continually generates and reproduces racial hierarchies, inextricably linking race and class—thus the term “racial capitalism”.

A central and radically hopeful notion in Black Marxism is that the power to bring about justice is constantly generated amongst and within the oppressed themselves. Robinson casts historical and contemporary rebellions as expressions of democracy. Not the prescribed democracy of the western tradition, but the uprisings of conscious masses against the brutal exploitation of Black labour and lives by a White capitalist oligarchy. He posits that the Black liberation movement began at the onset of the slave trade. Indeed, autonomous maroon societies in the Americas composed of runaway slaves and sometimes Indigenous populations were a form of concrete liberatory practice that predated—prefigured, even—Marx and Engels' theorizing.

The essence of Black Marxism is also reflected in Indigenous struggles past and present. The spontaneous Ghost Dance of 1890 illustrates one instance of Indigenous resistance (in this case, Lakota) arising from knowledge systems defying the genocidal policies that sought to erase their existence. Just as Robinson argues that Black struggles are anchored in African knowledge systems within the Black diaspora, Indigenous resistance is grounded in land-based knowledge and governance systems.

Cornel West, featured as a CCPA guest speaker during Black History Month last year, reviewed Black Marxism in 1988 in Monthly Review. He considered the work a “towering achievement” but also had important contrary insights. Still, he saw it as an important step in deepening the analysis of race and the Marxist tradition. Decades later, more and more organizers continue to adopt the idea of racial capitalism as a framework to understand the world.

Among its more prominent advocates is Ruth Wilson Gilmore, prison abolitionist and author of the recent Change Everything: Racial Capitalism and the Case for Abolition. She presents a brief synopsis of her views in a YouTube video Geographies of Racial Capitalism, in which she elaborates on her oft-quoted view that “capitalism requires inequality and racism enshrines it.” Robin D.G. Kelley, at UCLA, wrote introductions to the two most recent editions of Black Marxism and remains an articulate proponent of Black Marxism.

In recent years, many Asian American scholars such as Lisa Lowe (The Intimacies of Four Continents); Moon-Ho Jung (Menace to Empire); Jodi Kim (Settler Garrison); and Ikyo Day (Alien Capital) have also embraced the notion of racial capitalism. The concept has become so widespread that even the American Medical Association includes it as an item on its ‘health equity’ website.

In Canada? Not so much.

There are exceptions. Professor Ingrid Waldron (HOPE Chair in Peace and Health in the Global Peace and Social Justice Program, McMaster University) has taken up the concept of racial capitalism—and its corollary, environmental racism—in her book and movie There’s Something in the Water: Environmental Racism in Indigenous and Black Communities. So, too, have Shiri Pasternak of the Yellowhead Institute, SFU Labour Studies professor Kendra Strauss, and Rinaldo Walcott (University of Toronto) in his recent booklet On Property.

Robinson’s concept of racial capitalism provides depth to concepts such as settler colonialism and environmental racism. Furthermore, his emphasis on pre-capitalist notions that later become foundational to capitalism’s development, suggests an inherent intersectionality that targets other forms of pre-capitalist ideologies, including patriarchy, that later become part of capitalism’s fabric.

Black Marxism remains an essential work that anyone interested in the relationship between race and capital should study. Contemporary resistance against police brutality and incursions of state and pipeline corporations into sacred lands continue to affirm Robinson's brand of radicalism as a movement of the most oppressed people—their identity well-understood by themselves as subjects, and agents of change beyond a narrow analysis of class and capital alone.