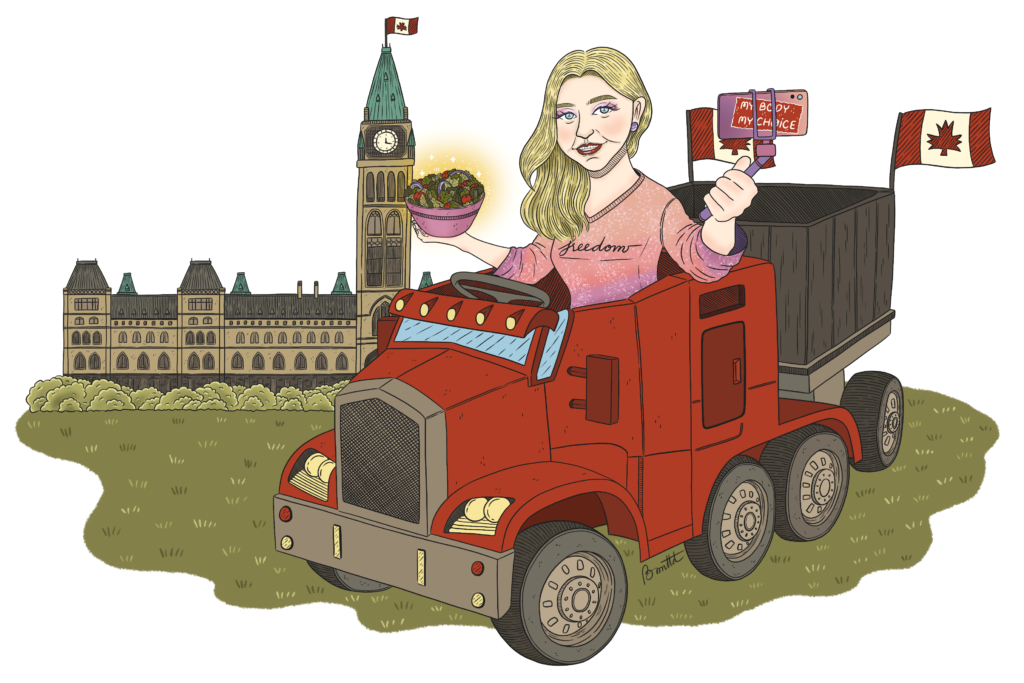

On January 28, the same day the trucker convoy rolled into Ottawa, Canadian food personality Angela Liddon posted an Instagram story fawning over the convoy.

“I can’t think of anything else except the [Freedom Convoy] right now. I get emotional thinking about how this movement has brought a lot of people out of a really dark place,” she wrote. “Our family has had many hard conversations over the past two years. What will our future look like if the government continues along the path of lockdowns, segregation, division/blame, mandates and censorship? Like many of you, that’s not the future we will accept for our kids. I want kids to be able to live freely again…to see their friends’ smiles…to play sports and SING…for ALL Canadians to be equal, free and to be able to thrive again. I’m curious, [Justin Trudeau], is this an ‘unacceptable view’?”

It might seem like a mostly innocuous statement—who can argue that all Canadians should be equal, free and able to thrive? But the reality is, the convoy was not about kids at all. It was a white supremacist movement, and Liddon’s Instagram story helped sanitize its message for her 600,000+ followers.

The trucker convoy was a white supremacist movement, not a protest

Yes, the so-called Freedom Convoy was ostensibly about vaccine mandates. However, if examined closely, it was clear from the very beginning that this “protest” was less about vaccines and more about overarching right-wing hate and paranoia.

Some of the organizers—Pat King, Benjamin Dichter, Jason LaFace (or sometimes LaFaci) and Chris Barber—have known links to white nationalism. As Global News reported, King loves antisemitism and racist conspiracy theories, particularly the idea that the government is actively trying to “depopulate the Anglo-Saxon race.” Dichter spoke at a People’s Party of Canada convention in 2019, where he said the Liberal Party is “infested with Islamists.” LaFace is a member of the Soldiers of Odin, the Canadian arm of a Finnish anti-immigration group that “organize[s] events that will try to stop immigration, people who are BIPOC or people who are in LGBTQ communities,” according to Carmen Celestini, a post-doctoral fellow with the Disinformation Project at Simon Fraser University. Other leaders, including Dave Steenburg, have also shared videos that imply an affiliation with Soldiers of Odin. Barber keeps getting banned from Facebook and TikTok for his racist posts, including a video he filmed in front of two Confederate flags.

But even if you missed all of that, it was obvious something was not quite right by the number of upside-down Canadian flags and Confederate flags that were in full view on their drive into Ottawa—well before Liddon made her post.

White supremacy has been part of the wellness industry since the very beginning

At first glance, Liddon doesn’t seem like she’d be a supporter of far-right movements. She started blogging under the name Oh She Glows in 2008 after suffering from an eating disorder for more than a decade. In the beginning, the blog was a hobby and a way to repair her relationship with food, but it quickly grew to encompass multiple popular social media profiles, a website and a slew of bestselling cookbooks. And while she likely didn’t realize it at the time, Liddon was entering the wellness space, which has always been a breeding ground for misinformation, exploitation and white supremacy—and would soon explode in popularity.

When I say white supremacy, I really mean it. The Nazis, for example, were hyperfixated on wellness, linking the idea of healthy, clean, good bodies with racial purity. According to philosopher Jules Evans, policy director for the Centre for the History of the Emotions at Queen Mary, University of London, “Hitler, Hess, Himmler and many other leading Nazis were into alternative medicine, organic and vegetarian diets, homeopathy, anti-vaxxing and natural healing. Hess, the deputy führer, opened a centre for alternative medical practices in Dresden in 1934. Himmler, meanwhile, supported alternative medicine—such as using plant extracts to heal cancer—and authorized experiments on prisoners in concentration camps for this research.” Their interest in healthy diets was actually about eugenics, while their well-documented love of yoga was really about using the practice as an “occult tool for purifying and exalting the individual body as a microcosm of the nation that would ultimately triumph over a [Jewish conspiracy] and impure invaders,” says yoga practitioner, writer and conspiracy theory expert Matthew Remski.

When yoga became the first tentpole of western wellness in the 1990s, those racist ideas became implicit instead of explicit, but they didn’t disappear. During this period, yoga’s deep breathing and intentional movement was immediately decoupled from its cultural and spiritual context and the practice instead became a way for (mostly) white women to feel better, especially in the face of traditional medicine’s bias against women.

"Racialized, Indigenous, queer, disabled & poor people rarely have access to wellness spaces... even though many wellness trends are derived from their traditional practices, then repackaged as 'ancient secrets' or 'mystical knowledge.'"

From there, wellness quickly grew to encompass other forms of fitness, healthy eating, personal care, nutrition, meditation, alternative medicine, spa services and weight loss—especially that last one. And its market share increased in lockstep with its popularity. A 2021 McKinsey & Company survey estimated the value of the global wellness market at more than US$1.5 trillion, while the Global Wellness Institute suggests it’s likely much higher: US$4.5 trillion. The market’s value is also likely to continue growing, according to a recent U.S. Chamber of Commerce report, which quotes Wendy Liebmann, the CEO of retail strategy and market research firm WSL Strategic Retail, as saying, “What this pandemic has revealed is that taking care and control of your own health—individual, family, home, etc.—is even more critical than before.”

Unsurprisingly, when companies learned they could offer a vulnerable group that was legitimately underserved tools and techniques to fill the gaps left by western medicine—and charge them a lot of money in the process—it further encouraged the rejection of western medicine, and by extension science, expertise and government authority. There’s a term for this: conspirituality, which “describes the sticky intersection of two worlds: the world of yoga and juice cleanses with that of New Age thinking and online theories about secret groups, covertly controlling the universe,” according to a 2021 Guardian article. “It’s a place where you might typically see a vegan influencer imploring their followers to stick to a water fast rather than getting vaccinated, or a meditation instructor reminding her clients of the dangers of 5G, or read an Instagram comment explaining that vaccines are hiding tracking devices.”

Liddon’s post fits right into white supremacist narratives

At the same time, racialized, Indigenous, queer, disabled and poor people rarely have access to wellness spaces as customers, much less the opportunity to become practitioners themselves, even though many wellness trends are derived from their traditional practices, then repackaged as “ancient secrets” or “mystical knowledge.” It all creates the perfect opportunity for white supremacy to flourish—and for the wellness industry to do serious harm.

According to journalist Terry Nguyen, “it’s ‘New Age capitalism’ at work: A robust system of knowledge is taken apart piecemeal, divorced from any philosophical or religious roots, and transfigured into a commodity, something that can be bought and sold to improve consumers’ lives.” She goes on to explain that cherry-picking meaning like this also makes it easier to layer political meaning on to personal choices. This is particularly true when it comes to food and nutrition influencers, who are often rich white women who gatekeep veganism.

She also quotes Remski, who argues there are fascist undertones in New Age beliefs. “Fascist ideas of the perfected body and earth [have] generated enduring cultural memes for holism, embodied spirituality, and health,” he says. “Those memes, sanitized of their explicit politics, carry jagged edges of perfectionism and paranoia about impurity. And that double message—your body is divine but it is also under attack—has become standard in the commodification of yoga and wellness.”

This just scratches the surface of how the wellness industry writ large and Liddon’s content specifically harmoniously fit with white supremacist viewpoints and attract white supremacist audiences. The innocuous nature of wellness content like that produced by Oh She Glows allows it to generate buzz and garner attention without raising red flags. Liddon’s work has been covered by Chatelaine, Canadian Living and House & Home, the Globe and Mail, the Toronto Star, the National Post, Cityline, the Food Network and more.

Angela Liddon isn’t the only wellness influencer to support the trucker convoy

While Liddon was the most notable example of wellness influencers to throw their support behind the convoy, she was far from the only one: their followers report seeing similar perspectives from food blogger Joy McCarthy of Joyous Health, fitness influencer Maddie Lymburner of MadFit and nutritionist Meghan Telpner, among others.

But while Liddon and her ilk are 100% responsible for their problematic views, I think media outlets should feel some sense of responsibility for the platform these influencers have now. These women may have built large and dedicated audiences on social media, but they simply wouldn’t have the power they do now if they didn’t also get buy-in from the media.

In recent years, the journalism industry has been discussing what it looks like to ethically cover white supremacy, which means taking a careful look at our own actions. It’s essential for journalists to explicitly name white supremacy instead of using “softer” terms like alt-right, which only serve to rebrand the racists. Some experts recommend avoiding interviewing these extremists entirely. During this news cycle, in particular, news outlets need to acknowledge the differences in how their journalists treat these protesters compared to how they have historically covered Indigenous and racialized protesters. And I think it’s fair to add to that list holding non-protesting sympathizers accountable, especially when they’re providing legitimizing and harmful rhetoric.

Because if we are going to play a role in creating platforms for people who may abuse them, don’t we also have a responsibility to at least act as a counter-weight to the misinformation they spread. Otherwise, we’re just going easy on white supremacists.

Illustrations by Doan Truong