The following text is the speaking notes used by Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives—British Columbia researcher Marc Lee in a Sept. 18 presentation to the House of Commons Natural Resources Committee. The Trans Mountain Pipeline expansion, Lee argues, is incompatible with Canada's climate goals or principals of good governance. Read the full presentation below.

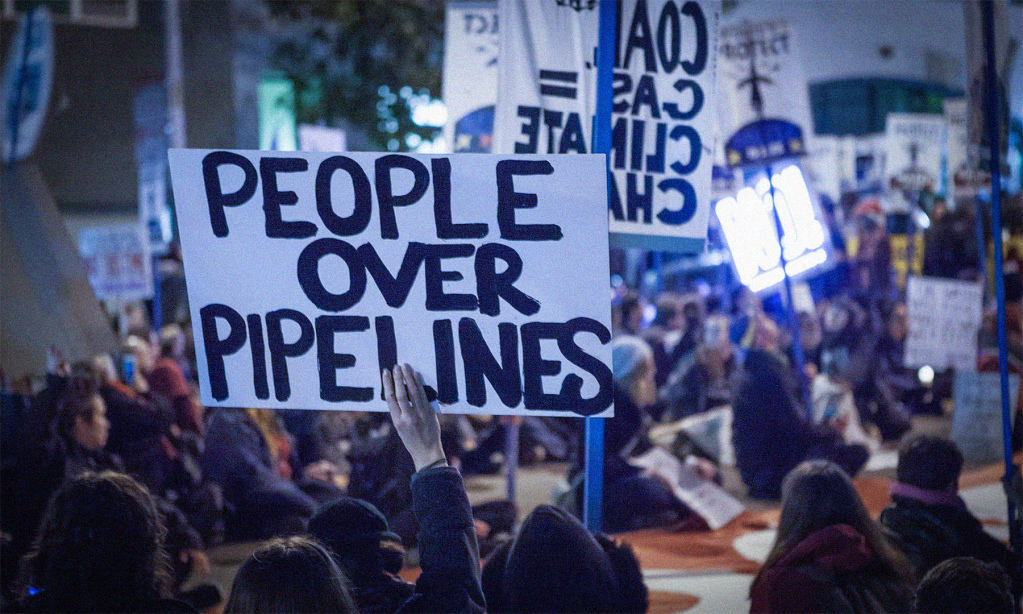

Thank you for the invitation to speak to the committee. I come to you as someone who has consistently been opposed to the expansion of fossil fuel infrastructure because of the existential challenge to humanity posed by climate change.

While Canada has made some progress towards transitioning to a cleaner energy economy, the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion (TMX) symbolizes the contradictions in Canada’s climate policy. TMX opens as a project that could not be more ill-fitted for the current moment in history.

I’m pleased this committee is looking into how costs could get so out of control and I’m puzzled at how so many could have signed off on much-lower cost estimates over the past six years. From an original estimate of $5.4 billion in 2013 and $7.4 billion when the federal government took over in 2018, final TMX costs have now been revised up to $34.2 billion.

Only a small portion ($1.4 billion) of this massive increase is attributed to 2021’s flooding and landslides, other extreme weather events and two years of COVID measures. The remainder is a long list of “project enhancements,” “schedule pressures” and higher financing costs.

Clearly, megaprojects like these cannot be guided by wishful thinking alone. They require comprehensive and independent assessment before any approvals are made.

The implications of the cost overruns are stark. A current concern is that TMX will provide ongoing public subsidies to the oil and gas industry by undercharging tolls for shippers relative to tolls that would break even on operating and capital costs.

Tom Gunton at SFU estimates a subsidy to Canada’s oil industry between $9-19 billion based comparing TM interim tolls to what a private sector firm would charge to cover operating and capital costs.

Final tolls will be determined in early 2025. It is imperative that the CER ensure cost recovery is either built into those tariffs or, as suggested by Gunton, into a specific levy per barrel (or ad valorum) on Western Canada oil production.

For the industry, these higher tolls (up to $9/bbl over previous TMP) will diminish gains from higher prices for exports—that is, by reducing the spread between WCS and WTI. There has been little apparent effect from TMX so far, though we are still in early days of operation.

Local impacts are also notable. UBC’s Werner Antweiler estimated that the increase in tariffs (applying to the old and new pipeline alike) will increase the local price of gasoline by 6 cents per litre, or $222 million per year BC-wide.

In terms of GHG emissions targets and the proposed emissions cap, if TMX successfully expands Alberta’s oil production, it will lead to additional carbon emissions. TMX would facilitate about 84 million tonnes (Mt) per year of CO2 emissions (about 25 Mt upstream and 59 Mt exported).

While most of those emissions will be in other countries and will not be counted in Canada’s GHG inventory, even the domestic emissions in Canada associated with this export growth will make it (nearly) impossible for Canada to meet its 2030 GHG target of 40-45 per cent below 2005 levels.

Also not counted above is the potential damage on land or on water from a pipeline or tanker spill. Such a spill would impose billions in clean-up costs, affect employment and devastate ecosystems. The greater presence of tankers in Vancouver harbour is already notable.

On the other hand, if the world is successful in acting to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the need for TMX vaporizes and we will be left with a stranded asset before the end of its useful life. TMX is a pessimistic bet that the world will not get its act together on climate change.