Five schools for the price of four—this is the deal the Pallister government got when it abandoned the plan to build schools through a Public-Private-Partnership (P3) model and used the usual public model instead. The government built five schools for the same cost using the regular process. In addition to being more expensive, P3s have been criticized for excluding local contractors, lack of transparency and loss of public control over taxpayer-funded assets.

So why is Manitoba looking at the P3 model again in 2023?

In growing communities, the need for new schools is pressing and will be an important talking point on doorsteps in the upcoming provincial election. Voters may not know the risks of P3s, but Manitobans need to prepare for more P3 proposals. Alongside the nine P3 schools announced last month, the province tendered an RFP to pre-approve consultants for work on P3 infrastructure projects across the Manitoba government.

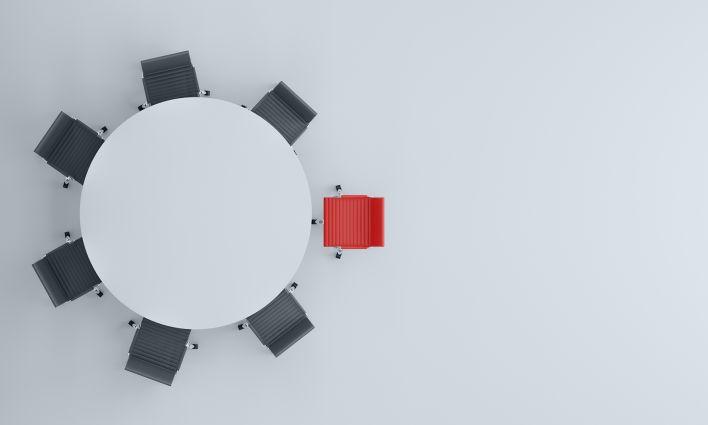

The usual public model involves several contracts with the local private sector: architects, engineers and construction firms. Government then either pays for the infrastructure through general revenues or borrows money, by issuing bonds, to pay for it. When construction is done, the government owns and operates the infrastructure—whether that be a highway, a school, or a hospital.

With P3s, generally, one large private sector firm is contracted to build, finance, maintain, and operate the project. The government leases the infrastructure back for public services, while the private company maintains ownership.

The Pallister government had retained KPMG to do a study on using the P3 model for schools. In 2018, KPMG recommended against it because they would cost more. The overwhelming evidence of costly problems related to P3s has not changed since then.

Canada’s history with P3 schools also hasn’t changed—everywhere it’s been tried, it’s been a disaster. Conservative governments in Alberta have twice abandoned the model—once because they were too expensive, the second time because of the restrictive controls private companies put on schools. Contracts with these private companies prohibited space from being leased to community groups like child care, sports leagues, and other after-hours uses. When school space was made available, the private owners charged on a for-profit, fee-for-service basis.

In Saskatchewan, teachers weren’t allowed to decorate classrooms or open windows, and the province is spending four times more on maintenance in new P3 schools than older schools owned by the province. In New Brunswick, the Auditor General found the P3 process lacked transparency, and there was no proof of cost savings. In Nova Scotia, former P3 schools were bought back from the company because leasing costs were so high. During the life of the contract, the province had to go to arbitration to settle issues over cafeteria revenue, after-hours fees, and insurance issues.

Manitoba’s ostensible reasons for returning to P3s for schools are speed and cost. Minister Teitsma argued that by bundling the construction and maintenance costs, the contractor would spend more upfront to keep major maintenance costs low. There is no reason why the Manitoba government could not also build better schools to save maintenance costs in the lifetime of the school. P3 projects do not take less time, they take longer to get started due to complex, and expensive, contract negotiations.

As the Pallister and then Stefanson governments have slashed taxes and revenue by $1.5 billion per year, one strategic reason for the Stefanson government to bring back P3s is that P3s cost governments less now but more later, after these politicians are long gone.

Governments borrow at much lower interest rates as they own significant assets and are low-risk. Evidence from the UK finds P3 repayment typically exceeds the cost of publicly financed projects after 15 years and is 40% more expensive than publicly financed projects over the project’s lifetime because borrowing costs for private financing is high. The UK Auditor General found interest rates for P3s were 2-5% percent higher. On Manitoba’s previous proposed P3 schools’ $100 million project, interest payments over 30 years at a 4% interest rate would be $73 million versus $166 million at 8%—more than double. Taxpayers would bear the cost of repaying these higher financing costs.

The UK is one of the first countries to see the long-term impacts of the P3 model on the public purse. These were so significant that the UK decided to abandon the P3 model altogether, citing its “significant fiscal risk for government.”

In Canada, Auditor Generals in five provinces have released reports heavily critiquing P3s for the high expense to the public purse and taxpayers: New Brunswick, Quebec, Ontario, Saskatchewan and British Columbia. The Auditor General of Canada found the value-for-money analysis done to justify P3 projects downplayed their costs while inflating the cost of the traditional model.

After critiques of the Chief Peguis Trail and Disraeli Freeway P3 projects’ lack of cost/ benefit analysis, the Selinger government introduced legislation requiring a value-for-money assessment of P3s. But the Public-Private Partnerships Transparencies Act was eliminated in 2017. The value for money approach needs to be used carefully. P3 value-for-money assessment methodology is often held privately by consultants, away from public scrutiny.

P3 contracts are not available to the public, so public interest groups cannot review past P3 projects to assess costs. Minister Teitsma argued that Manitoba’s P3 contract would be improved from other jurisdictions and control costs and public school access. The public, however, won’t have access to the contract to assess the exact agreement. These are held as confidential due to corporate interests.

So again, why P3s now? Many high-profile corporate leaders sit on the Canada Council for Public-Private-Partnerships. They are a powerful group and will continue to push and “shapeshift” procurement processes across Canada in favour of the P3 model as it represents a massive opportunity for profit to the private sector at taxpayers’ expense.