This is part two of a three-part series on the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on women's economic security in Canada. Part one, Frontlined and sidelined: The year COVID-19 upended women’s economic security, is available here.

Bolstering household incomes and shoring up women’s employment

The COVID-19 pandemic has revealed women’s all too tenuous foothold in the paid labour market. Governments need to step up with a plan that both addresses immediate economic needs and lays the foundation for an economic recovery among women that reverses long-standing inequities in Canada.

Lacking an effective or appropriate income support program, the federal government moved quickly to create the Canada Emergency Response Benefit (CERB) in March to “pinch-hit” for EI, dramatically increasing the share of workers covered, making it easier to apply and offering more generous benefits to effected low-wage workers.

The other critical feature of the CERB program for families, and mothers in particular, was the more expansive approach to providing support to parents and caregivers. It adopted the same approach with the suite of recovery benefits introduced in September (e.g., CRB; CRSB; CRCB).

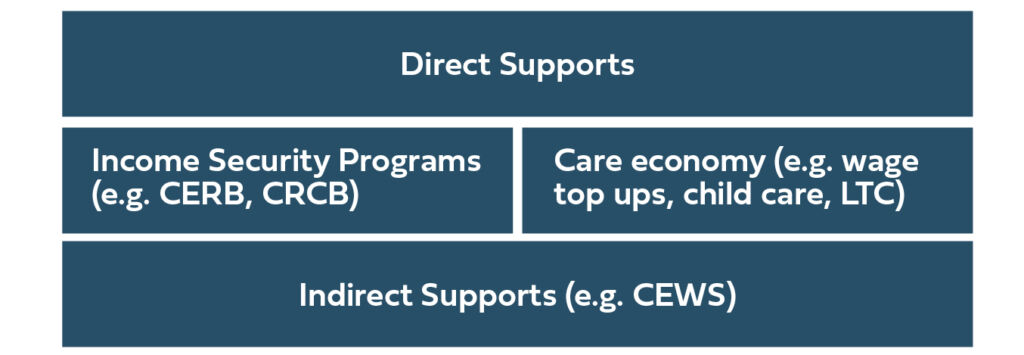

Targeted investments in the care economy, largely funded by the federal government, delivered by the provinces, have also provided critical support to female workers impacted by the pandemic – both the workers engaged in essential care work and women more broadly who rely on these services to care for their families and support their paid employment. These include:

- Different provincial schemes to top up the wages of essential workers;

Investments in long-term care, selected community services and child care – all female majority sectors.

These programs have been introduced to stabilize service and stop the hemorrhaging of staff at a time of acute community need.

The number of female recipients in mid January was 6.5 times larger than in February 2020 – further evidence of the profound gender-bias of the pre-COVID-19 program.

Income benefits have protected women.

Figures on program take up illustrate their broad impact.

Between April and September, the Canada Emergency Response Benefit provided an unprecedented level of support to 8.9 million individuals, including 4.3 million women (48.5% of total recipients) and 4,700 gender diverse people (0.5%).

In the program’s last month, over half of the roughly 4 million CERB beneficiaries (54.8%) were women. Large numbers of new immigrants and racialized Canadians were receiving support as well, comprising 13% and 14% of total September applicants, respectively.

The need for ongoing support is still high. In January 2021, there were 2.2 million unemployed workers receiving EI benefits, 1.1 million or 49.0% of whom were women.

This represents a significant increase in both the number of female EI beneficiaries and their share as compared to men, directly as a result of the new “temporary” eligibility rules for EI introduced in October and the second round of economic closures.

The number of female recipients in mid January was 6.5 times larger than in February 2020 – further evidence of the profound gender-bias of the pre-COVID-19 program.

Another 1.6 million workers had received the Canada Response Benefit between October and January, including roughly 700,000 women, 45.8% of total applicants, while 354,000 workers had applied for the Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit. Just under half of CSB applicants were women (at 47.7%).

As of January 10th, 286,000 workers had applied for the caregiver benefit since October, a figure that jumped by 27,000 by the 24th, as school boards in several provinces announced closures to attempt to contain escalating community infections in the aftermath of the holiday season.

For women, an important feature of the CERB and the recovery benefits has been that they are targeted to individual workers and are not, unlike many other federal benefits, subject to a family income test. This feature has ensured that female workers impacted by COVID-19 are not precluded from receiving support.

In combination with the one-time transfers, Canada’s income support programs are delivering substantive support.

Most would not even have the resources to make ends meet for even one complete month of joblessness. This was the case for over half of all single mothers (56.3%) and roughly half of Indigenous households living off reserve (46.9%) and households headed by a recent immigrant (49.7%).

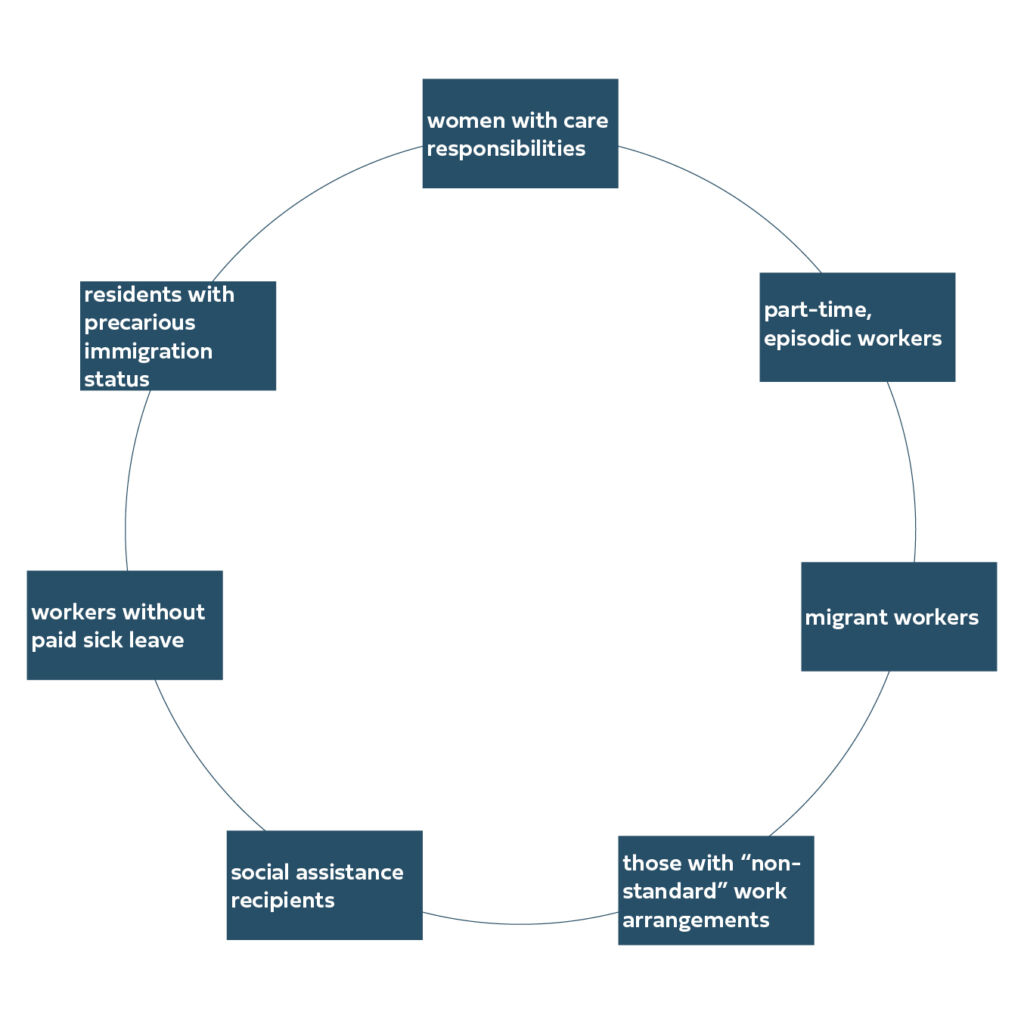

At the same time, many are falling through the cracks

At the same time, many of the most vulnerable continue to fall through the cracks, including those who have not qualified for any support at all such as the estimated 1.8 million migrant and undocumented workers working on the frontlines of the crisis or sex workers who because of the precarious and criminalized nature of their work, do not qualify for CERB or other emergency income supports.

Social assistance recipients have also been left to struggle on incomes substantially below the poverty line in all provinces and territories, including people with disabilities, youth aging out of care, people fleeing violence and single parent families.

There is a long history of the inhumane and unjust treatment of social assistance recipients – including women, mothers and others who don’t neatly fit the “productive worker” mold and pay the price in high rates of poverty and ill health, out of view of the broader public. Today, those forced to rely on welfare are again out of view, overlooked in the pandemic economic responses largely focused on the employed.

Individuals and families on the margins of Canada’s pandemic recovery efforts

Other groups of precarious workers are poorly served by the new programs meant to do the heavy lifting

The inability of the EI system to gear up to meet the needs of people thrown out of work speaks volumes about the biases baked into the program

David Macdonald estimates that roughly three-quarters of a million CERB recipients, mostly women (56%), did not qualify for any support when the government wound down the program. The large majority were those low wage part-time workers who made less than $1,000 per month. They are now not eligible for EI regular benefits or would receive only a meagre amount through EI’s working while on claim program.

The Canada Recovery Sickness Benefit is failing also to assist many workers as evidenced by the decline in successful applicants over the course of the fall even as COVID-19 cases began to rise again. For workers working pay cheque to pay cheque, the time it takes to apply for, and to receive, a separate benefit is proving to be prohibitive. Low income workers are choosing work over health and safety because they cannot afford to do otherwise.

Like the Canada Recovery Benefit, the new Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit (CRCB) is also a smaller program than the CERB. “Women may seem as if they’re making a choice to step back, but as often as not, the choice isn’t really one. It’s not a choice to care for your children when schools are closed and child care costs as much as your take-home pay.”

The gap between what’s needed to strengthen women’s labour market position and what’s on offer is readily evident in the “uneven” investment in caring services across the country.

Investments in care are hit and miss, mostly miss

The gap between what’s needed to strengthen women’s labour market position and what’s on offer is readily evident in the “uneven” investment in caring services across the country.

Child care, home care and long-term care are all “inequitably distributed, insufficiently available and of uneven quality,” staffed by a mostly female, largely racialized workforce who are “underpaid, underappreciated and inadequately supported.”

Barriers to access are especially high for Indigenous communities, people with disabilities, racialized groups, rural communities and women and their families reliant on precarious employment.

Still waiting: Child care

Federal funds allocated to support the crisis ($625 million) fell far short of the $2.5 billion that advocates were calling for to stabilize revenues and staff losses and enhance service delivery to meet new safety standards for children and staff.

Provincial funding (net federal contributions through the Safe Restart Agreement) represented just under half (49%) of total monies spent on pandemic-related support for child care between March and December.

Among the provinces, British Columbia made the largest investment in its child care services (at $282 million) on top its share of available federal funding.

The Saskatchewan government, however, has yet to fully allocate the federal funds it received for child care, while Alberta and Manitoba have contributed very little of their own resources to bolster child care in their jurisdictions – despite women’s lagging employment recovery and the imminent loss of child care spaces in these provinces.

While women and families in Quebec suffered significant employment losses associated with high rates of community infection, the relative strength of the child care system helped to offset its impact of women aged 25-54 years whose participation rate had rebounded by September and was relatively stable through the fall.

The size of Quebec’s child care system also helps to explain the relatively low take up of the Canada Recovery Caregiving Benefit among female workers (as compared their share of Canada’s workforce); in December 2020, women in Quebec accounted for 23.2% of total female employment but only 15.4% of CRCB applicants. Even as women lost their jobs or were forced to reduce their hours, many had access to child care to support their return to work.

By contrast, the share of female applicants compared to their share of total employment was much higher in Alberta (15.9% vs 11.6%), Manitoba (7.4% vs. 3.2%) and Saskatchewan (6.8% vs. 2.9%) – all provinces with much smaller child care systems.

Still waiting: Essential workers

In mid April, as the tragedy in long-term care homes was unfolding, the federal government announced its intention to create a program to support low-wage essential workers working in very difficult circumstances at great personal risk.

Federal funds were made available to provinces on a cost-shared basis (75% federal: 25% province) to provide wage top ups to frontline workers. The programs were designed and administered by the provinces, some providing additional funds to expand the number of workers covered and to boost funds available to individuals.

Quebec launched its program before the federal government’s funding was announced. The province through different programs gave a 4% raise to more than 250,000 public and private sector health and emergency service workers, with another 4% on top of that for 55,000 workers in areas where they are likely to be exposed to the virus, like intensive care units.

Five out of 10 provinces (Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and British Columbia), however, chose to leave federal money for essential workers on the table – a total of $126 million.

Saskatchewan, for example, matched only 5.2% of its available funding and chose not to access almost $50 million in additional support, neglecting the opportunity to invest in Saskatchewan’s majority female care workforce.

Alberta finally announced its program for workers in the public and private sector essential workers in February 2021, waiting fully nine months before confirming their support. Eligible workers will receive a flat of benefit of $1,200.

The suggestion, widely expressed at the time, was that Canadians were truly seeing the extent to which society relies on the labour of essential workers, that the pandemic would herald a reckoning about the place and treatment of workers in the care economy. These workers are still waiting for this conversation to begin.

In Ontario, even as the government brought in a wage top for workers in long-term care settings, it failed to take action to improve working conditions and institute proven measures to halt the spread of the virus.

The crisis highlighted the critical importance of caring labour – hiding in plain sight – but has not yet prompted a fundamental rethink of its organization and practice. The scale and focus on Canada’s economic response continues to fall short of meeting the pressing need of female workers.

Join Katherine Scott and Anjum Sultana for a lunchtime discussion of women and the economic crisis, the Canadian response to date, and what comes next today (Friday, March 12) at 12:00 pm EST. Click here to register.