While some have welcomed the scrapping of Regulation 274/12, announced by Minister of Education Stephen Lecce on October 15th, there is limited discussion about what new hiring mandates will entail, and minimal information available as to how the revocation will increase representation for BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, People of Colour) teachers who are grossly underrepresented in permanent teaching positions.

Regulation 274/12

Regulation 274/12 was enacted in 2012 under the Ontario Education Act, specifically to ensure transparent, fair and consistent hiring practices for both permanent and long-term teaching positions (ETFO, 2012). It required that all publicly-funded school boards create and maintain two lists, one for Occasional Teachers (OTs) and one for Long Term Occasional Teachers (LTOs). Occasional Teachers were able to apply to the LTO list once they had completed a year on their respective board’s OT roster.

The purpose of the lists was to assign seniority numbers to candidates to comply with hiring mandates. Therefore, when hiring for permanent teaching positions, candidates from the LTO list with the top five seniority numbers and the required qualifications would receive an interview.

The common assumption is that the person with the highest seniority will automatically receive the job offer, but candidates must meet all requirements and also have the experience or seniority to be considered qualified for an interview. Should none of the top five senior candidates be selected, school administrators are able to continue down the seniority list until a candidate is hired.

Although the Regulation is far from perfect, it provided many teachers with a framework for accessing permanent employment and offered many the opportunity to access an interview and showcase their skills, experience and qualifications. The removal of Regulation 274/12 without critical anti-racist transformative policy, practice and oversight will likely exacerbate the underrepresentation of permanent racialized teachers in the province as administrators are allocated sweeping autonomy to make hiring decisions.

Several BIPOC teachers were asked to produce identification before entering the building, had their credentials questioned, and were asked about their ability to communicate in English. These were experiences that White participants had not encountered.

Teacher Hiring and Underrepresentation

Based on census data and extant studies, although Ontario is often touted for its diversity, permanent teaching and administrative staff remain overwhelmingly White (Abawi & Eizadirad, 2020; Abawi, 2018; Turner, 2015; Ryan et al., 2009). This speaks to larger social and economic trends in Ontario, such as the overrepresentation of BIPOC people in precarious non-permanent employment relationships and poverty (Block & Galabuzi, 2011; Lewchuk, et al, 2013; United Way, 2019).

Despite an onslaught of equity, inclusive and diversity educational policies, hiring initiatives have centred on bias-free, objective hiring policies as best practice for increasing teacher diversity. This has perpetuated the status quo of Whiteness in the teaching profession as the power relations, which inform and encompass hiring practices have remained unacknowledged. Racialized teachers who do not receive their training in Canada, also known as Internationally Educated Teachers (IETs) face further barriers in credential recognition (Pollock, 2010).

Access to teacher education programs continues to be racially stratified:while teacher education programs provide the option for applicants to ‘self-identify’, the admissions demographic data is not released making it difficult to gage if faculties of education are complying with their stated diversity objectives (Abawi & Eizadirad; Abawi, 2018; Childs et al., 2010).

For my own research into the “teacher diversity gap” (Turner 2015), I interviewed 10 teachers of various backgrounds and teaching assignments, employed in publicly-funded schools in Ontario to understand the experiences of teachers of different racial backgrounds in accessing permanent teaching employment. The findings suggest that BIPOC teachers have markedly different experiences in navigating teacher recruitment and hiring processes. For example, several BIPOC teachers were asked to produce identification before entering the building, had their credentials questioned, and were asked about their ability to communicate in English. These were experiences that White participants had not encountered. These microaggressions speak to oppressive practices that serve to marginalize BIPOC students, families, teachers and communities.

While most participants agreed that Regulation 274/12 contained flaws and loopholes for favouritism and nepotism to continue, many believed it provided some consistency and accountability for securing permanent work.

Paving the Way Forward

Although Regulation 274/12 is in need of significant revisions to ensure transparency and authentic equity, its removal will remove any democratic practice of hiring and allow educational administrators the authority to choose subjective criteria concerning the best-qualified candidate and merit.

To recruit more BIPOC teachers in Ontario, I suggest:

• The implementation of mandatory data collection for publicly-funded boards, in order to determine if boards are adhering to their commitments of diversifying the teacher workforce;

• Embedding an anti-racism approach to the Principal’s Qualification Program;

• Re-framing equity, diversity and inclusion from an anti-racist perspective rather than from a Eurocentric, multicultural approach and one which is in consultation with grassroots organizations (families, students and community activists);

• Mandating that Ontario school administrators undertake critical self-reflective practice work to unpack how their positionality (White privilege and identity) impact hiring decisions.

Whose Merit?

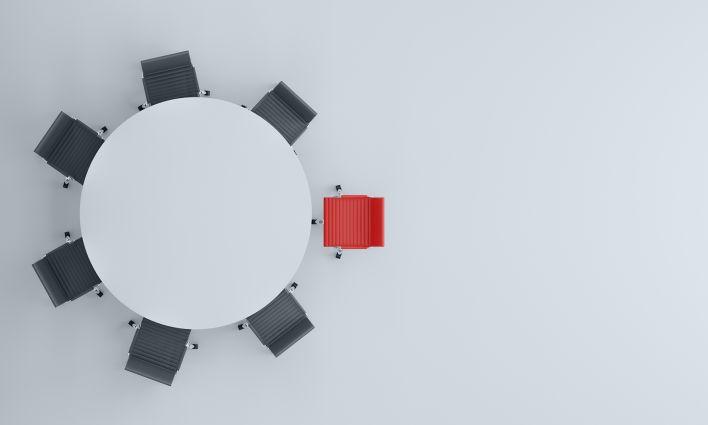

The educational diversity gap peaks at the administrative level: only 2 percent of principals and 5 percent of vice principals identify as racialized (Turner, 2015). It has been widely noted that individuals charged with hiring often hire those that resemble their own social locations (Rivera, 2012). The revocation of Regulation 274/12 will only provide more agency to majority White school administrators to make hiring decisions whilst omitting any checks and balances. This in turn will make the hiring process and pathway to permanent teaching employment more ambiguous and challenging to navigate, as school administrators are given more autonomy to determine their own notions of merit and ‘the best fit’ for their schools.

Further, neoliberal constructs of equity, diversity and inclusion pay lip service to diversity hiring initiatives, while failing to acknowledge and name endemic racism and White privilege that prevent access to and silence ongoing and historical inequities of BIPOC communities. So long as diversity, equity and inclusion policy initiatives operate through the guise of neutral, objective and merit-based hiring, BIPOC teachers will continue to be underrepresented in permanent teaching and leadership roles. Therefore, the relationship between overly White administrators in relation to applicants must be unpacked to engage in self-reflective practice on the ongoing barriers and biases encountered by BIPOC educators seeking permanent teaching employment. Without this essential dialogue, the teacher diversity gap will be reinforced through the guise of “best fit” neoliberal meritocracy, while simultaneously omitting any candid discussion on race and power relations (Bonilla-Silva, 2006). While Regulation 274/12 at least provided BIPOC teachers with the chance to have an interview, gain interview experience and network with educational administrators, its revocation will likely leave many languishing in precarious and unstable labour.