Pat Armstrong’s work first came to my attention back in the 1980s when I landed a job compiling a syllabus for the first ever “women and politics” course at Queen’s. The students had been clamouring for a course in the politics department for ages and I was thrilled to get the opportunity to spend all summer reading feminist theory and history.

Of course, the department hadn’t actually hired a feminist scholar to teach the course. Rather, one of the all-male theory group stepped up—which is why I ended up scanning Canadian feminist literature all summer, including Pat’s book: Labour Pains, and Meg Luxton’s More than a labour of love. Both were ground-breaking studies of women’s labour—and the ways in which it is defined and organized by different systems of power and oppression.

Pat played a critical role challenging the idea that “women” were just another social category or concept, an “add-on” to traditional political economy. Rather, as she and her partner and collaborator Hugh Armstrong argued in “Beyond Sexless Class and Classless Sex”, the gendered division of labour was central to the workings of capitalism. Her scholarship helped build out the theoretical and practical underpinnings of the field—highlighting, in particular, the struggle over social reproduction and the role of the state in securing not only capital accumulation but the subjugation of women and other marginalized groups to this end.

Such conflicts have always been central to capitalist society, which, at one and the same time, relies on reproductive labour while disavowing its value. But these conflicts are particularly acute today in our neoliberal era that demands ever more hours of waged work while at the same time reducing and subverting needed public provisioning and support – squeezing women, families and communities to their limits, a process experienced mostly acutely by marginalized women.

Feminist political economy in action

Those who study feminist political economy have grappled with the “crisis in social reproduction” over the last four decades, bringing a set of theoretical and methodological perspectives and tools to the task, deepening our understanding of its intersectional dimensions and impacts.

This has not been a linear process. The preoccupations and priorities of feminist political economy have been contested each step of the way—within the academy and beyond. Feminist political economy practitioners have been rightly challenged to take into account the varied experiences and social locations of those who provide care and those who receive it. We’ve been pressed to confront our own biases, blind spots and privilege.

The field today is much stronger as a result of these struggles. It certainly has greater reach. Once the remit of a relatively small group of socialist feminists, feminist political economy now touches many more disciplines – from urban planning to epidemiology to migration studies and beyond.

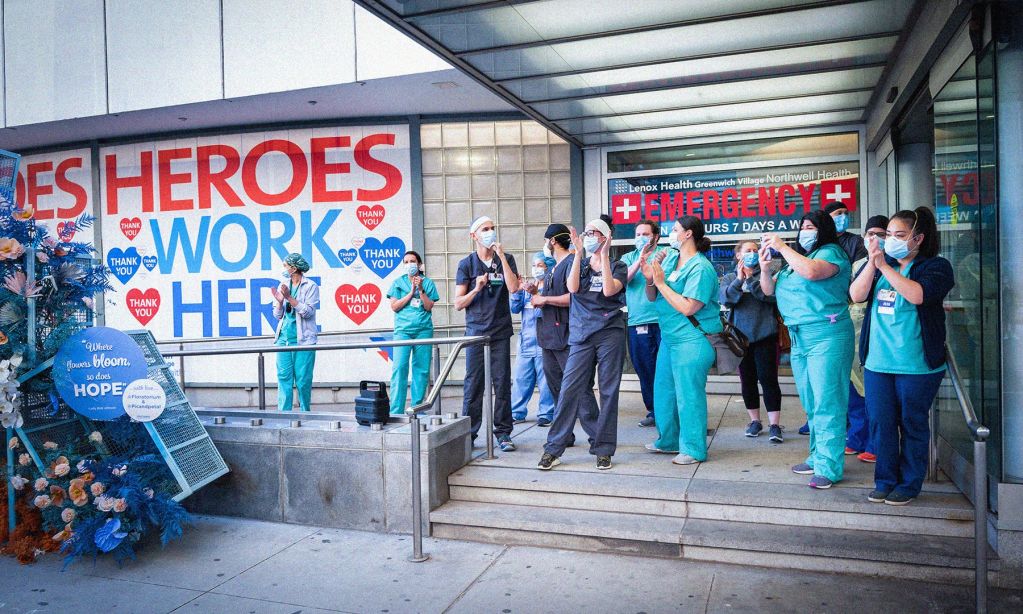

Feminist political economy has been successful influencing “real-world” policy-making, too—look at our collective efforts to describe and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic. If ever there was an example of feminist political economy in action, this was it.

Feminist researchers, community advocates and progressive movements from around the world quickly mobilized to document the myriad of ways in which the pandemic was impacting women’s lives and further undermining the position of marginalized communities affected by institutionalized poverty, racism, and ableism. They led the call for a gender-just recovery that would both respond to immediate needs and advance systemic reform.

Pat was at the forefront of these efforts in Canada, working to illuminate the devastating and wholly predictable tragedy unfolding in our long-term care facilities – the consequence of our appalling lack of care for vulnerable seniors, as evidenced by our reliance on for-profit service providers and our negligent and exploitative treatment of care workers.

Likewise, feminist groups stepped up. For example, B.C.-based Feminists Deliver was one of the first to release a feminist recovery plan in July 2020. This plan—and others—were squarely located in the feminist political economy tradition, providing a narrative frame for understanding the pandemic’s intersecting dimensions, while stressing the imperative to tackle the crisis in care and its disproportionate gendered impacts head on.

This isn’t to say that governments listened.

On the one hand, the federal government, for its part, clearly acknowledged the gendered character of the COVID-19 crisis and its impact on women’s paid and unpaid labour. And its policies delivered on poverty reduction. Emergency pandemic benefits played a vital role in supporting individuals and households in the face of mass unemployment, more than offsetting what would have been a staggering rise in poverty.

The federal government also channelled $8.6 billion to bolster care services through several federal-provincial-territorial agreements, including targeted funding to address critical labour shortages and catastrophic service failures in long-term care and to stabilize service delivery in the child care and the GBV sector.

But, on the other hand, there were considerable gaps in Canada’s overall response. Women on social assistance, among the poorest of the poor, were left to struggle on incomes substantially below the poverty line as community services shut down. Migrant care workers were literally locked in the homes of their employers, working 10 to 12-hour days, seven days a week, with scant protection or oversight.

The gaps in response were even greater at the provincial level – especially as they related to care. My research shows that provincial spending on “gender-sensitive” measures ranged from a high in British Columbia at $844 per capita to a low of only $50 per capita in Alberta, Canada’s wealthiest province. (The provincial average was $357 per person but eight of the 10 provinces fell below this benchmark. Indeed, six were less than $100 per capita mark.)

Had federal transfers not been available or tied to specific goals, the number of provincial programs qualifying as gender-sensitive would effectively have been zero. Five out of 10 provinces, for example, actually chose to leave federal money for essential workers on the table. In Saskatchewan’s case, it amounted to almost $50 million.

Coming full circle

This fundamental disconnect between graphic need and this set of policy outcomes is perhaps not a surprise – certainly not to those who study feminist political economy.

The political and institutional factors that were in place in 2020, which helped secure crucial investments in child care, gender-based violence services and poverty reduction, were not enough to deliver on the promise of gender-justice—certainly not in a country where the response to the pandemic hinged on subnational levels of government, many of which were wholly silent—if not outright hostile—to the idea of addressing the pandemic’s gendered impacts.

Indeed, a backlash against feminist movements and investments in the care economy has gained momentum over the last two years. Financial elites and mainstream economists are mounting a campaign for renewed public sector austerity and higher interest rates to contain inflation. The emergency programs that helped protect household incomes and spur economic recovery are now being blamed for higher inflation and rising living costs.

This does not diminish our collective achievements, or the insights of feminist political economy, but these gains must be measured against the scale of the political challenge.

The pandemic represented a political and economic rupture … a moment when the case for child care was taken up on Bay Street, when the plight of foreign temporary workers made headlines across the country, when the redistribution of reproductive labour between market, state and households seemed tantalizingly possible.

That moment has passed. But what of the next moment?

We would do well to reflect on the lessons that Pat has taught us. Her clarity of vision; her collaborative approach to teaching and research as well as policy making; her laser focus on what’s needed to advance fundamental change; her commitment and respect for those who receive and those who provide care; her hope for the future. These are the building blocks of the change we all aspire to.