One year out from a provincial election, two different stories are emerging about Ontario’s finances.

The first comes from Finance Minister Peter Bethlenfalvy. It goes like this: because of COVID-19, Ontario has a record budget deficit and we need to reduce it. Many people think this can only happen if we raise taxes or cut public services, or both, but that’s not so, says the minister: through the miracle of economic growth, we can spend more on public services and reduce the deficit at the same time.

“Some will claim that balancing the budget will require cuts to public services or higher taxes down the road, but we will choose another path,” the minister said back in March. “Our recovery will be built on a strong foundation for growth, not painful tax hikes or cuts.”

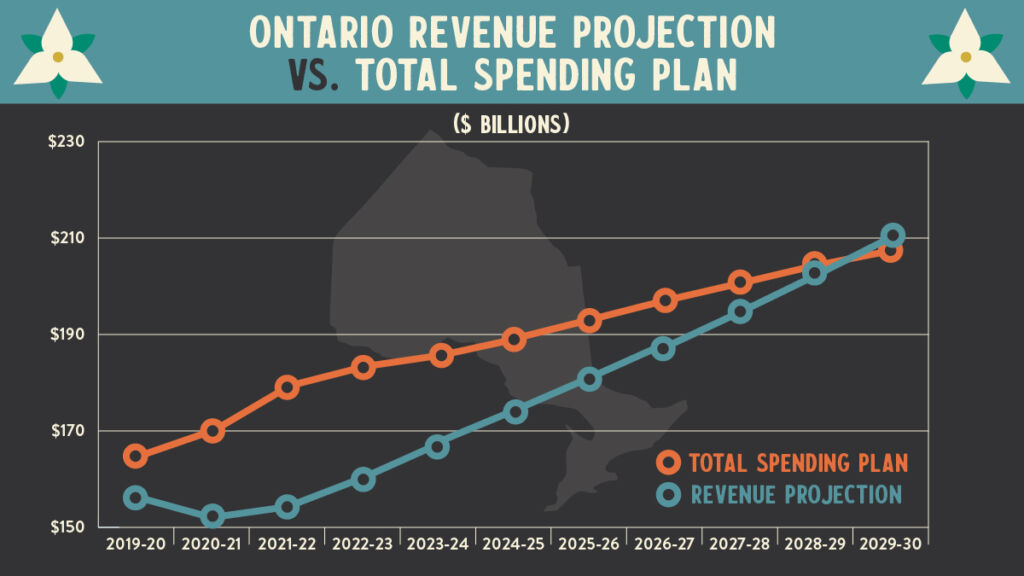

The chart below shows how the future unfolds in the minister’s story. The red line is provincial spending on public services and interest on debt; the blue line is revenue. At the start, spending is higher than revenue, but over time, as revenue grows faster than spending, the lines cross, and the budget deficit is gone. It takes 10 years, but it’s totally painless, Bethlenfalvy says.

“Expenditures do go up every year,” he said when the 2021 budget came out. “I said that there would be no cuts, and this budget very clearly demonstrates that.”

That’s one way to look at it. Unfortunately, the minister’s version leaves out some very important facts.

To tell the full story about funding public services in Ontario, we need to look at what we actually need. That means taking inflation into account. It means taking population growth into account. And it means recognizing that an aging population requires higher spending, especially in health care.

Just as importantly, telling the truth about spending in Ontario also means recognizing that current levels of investment aren’t enough. We need faster investment in long-term care. We need to support students as they recover from the disruption of COVID-19 and tackle the $16-billion school repair backlog. We need to lift people on social assistance out of poverty. We need a plan for the environment that goes beyond picking up litter. And so on.

The government isn’t interested in new spending, though. Its current fiscal plan won’t even maintain public services at current levels.

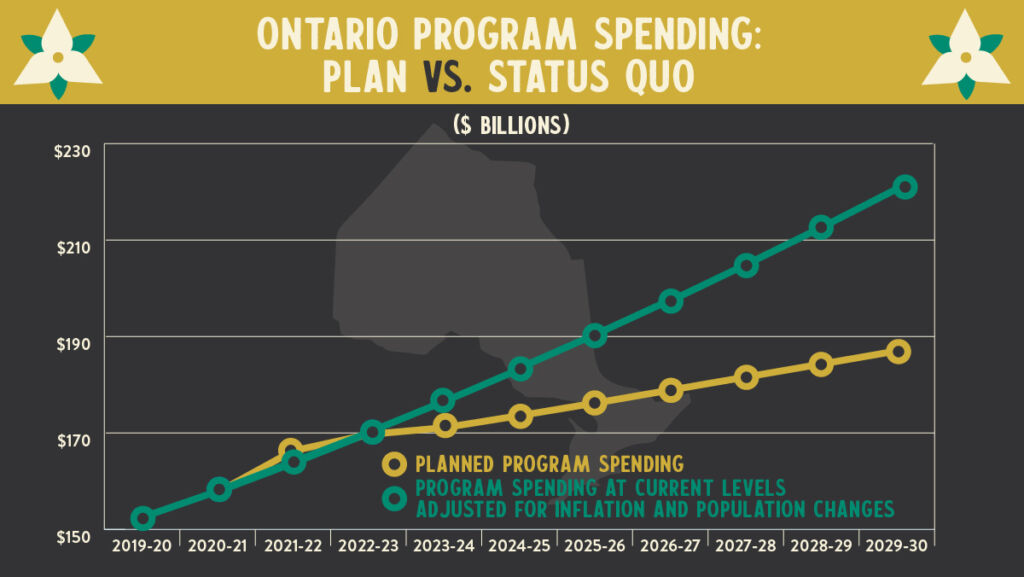

Thanks to the Financial Accountability Office, we can estimate that because of inflation and population changes, overall provincial program spending has to grow by 3.8% per year just to maintain current public service levels. According to the 2021 Ontario budget, program spending over 10 years (not including short-term COVID-specific spending) is set to grow at an average annual rate of 2.1%. Thus, the funding gap between what’s needed to maintain services and what the government plans to spend averages 1.7% annually.

This year and next (an election year), planned spending is expected to maintain services overall, more or less. After that, though, there’s a gap between what’s needed and what’s planned. That gap grows bigger each year, reaching $33 billion in 2029-30. Put another way, the finance minister’s long-term plan is to cut per capita funding to public services by 15% compared to the current level.

That is a huge cut by any measure.

A 15% cut would be bad enough if Ontario were a big spender. It’s not. When it comes to public programs, Ontario is already dead last in Canada in per capita spending. Before the pandemic, Queen’s Park spent $2,000 a year less, per person, than the average of the other provinces. Further cuts would be devastating.

The obvious and better alternative is to raise revenue, something the government seems unwilling to do. “Historically this government, and our party, has not been the ones to raise taxes,” Bethlenfalvy told a reporter not long ago. “As you know, we’ve been reducing taxes.”

The government’s tax cuts during this term in office are currently costing provincial coffers at least $4 billion a year, leaving that much less for public services.

The only source of new money Queen’s Park appears to approve of is the federal government. Bethlenfalvy and Premier Doug Ford both insist that Ottawa is short-changing the provinces on the Canada Health Transfer.

This claim, which has been rightly called “disingenuous at best and dishonest at worst,” is also, in the case of Ontario, irrelevant. Given that the people of Ontario are net contributors to the federal government, the Ontario government is essentially asking the feds to raise money from Ontarians and then hand it over to the province. There is no reason why Queen’s Park can’t raise the money itself, right here at home.

It’s worth underscoring that the health and economic costs of COVID-19 have not been shared equally. Millions of Ontarians and thousands of companies will come out of the pandemic better off financially—in some cases, dramatically better off—than they went in. Now is the time to lay out a plan for fair and progressive tax increases to rebuild our public services.

Over the next 12 months, Ontarians will hear the finance minister say, repeatedly, that his budget plans are built on economic growth, not cuts to public services. That’s just not so.

It’s up to the rest of us to tell it like it is.