Oil prices have risen to US$90 per barrel for the first time since 2014, more than four times where they were when prices bottomed out at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Most major economies have bounced back from pandemic-induced contractions and recessions. In November, Canada’s GDP finally caught up to February 2020 levels. That resurgent economic growth is driving global demand for oil, which is, in turn, driving rising prices.

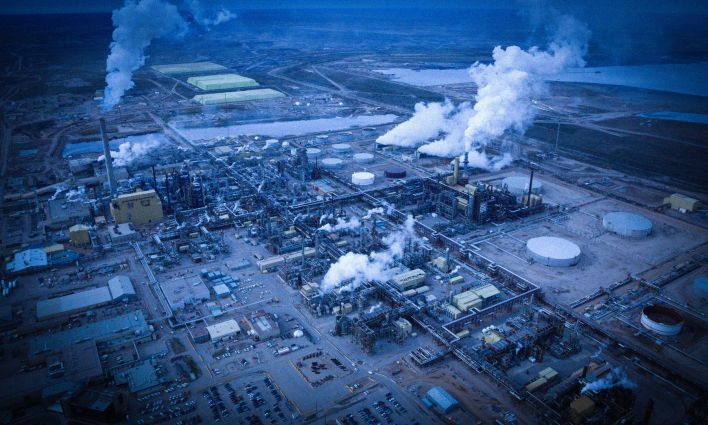

The Canadian oil industry is jubilant. High prices means more profit, which, they claim, will lead to more investment. The oil and gas lobby expects a 33% increase in oil sands investment this year over last year. According to the industry, that investment will “support jobs across the country…for decades to come.”

It’s an alluring promise for oil workers and their communities, many of whom have lost their livelihood in the past five years. There was a time when the industry’s promises of long-term job creation might have been true. From the early-2000s to the mid-2010s, high prices incentivized oil companies to start a lot of new “greenfield” projects. Building these new plants created a lot of work, especially in the in situ operations that are the mainstay of bitumen extraction in the oil sands.

Unfortunately for workers (this is bad news for the climate, too, but we’ll get to that), major oil projects become less dependent on labour and much more reliant on specialized equipment once they are up and running. Once construction is complete, there are simply fewer jobs involved in operating an oil plant or an oil pipeline.

When oil prices dropped in 2014, it put a halt to many new projects, which led to a big drop in oil and gas employment, but oil production continued to rise. Today, Canada is producing more oil and gas than ever before, even though oil and gas employment is back where it was in 2006, which is more than 20% below its 2014 peak.

If prices are rising again, why shouldn’t we expect a lot of new jobs this time around? Mainly because oil companies are spending differently than before. Rather than invest in new oil extraction projects, companies are (a) paying out more profits to shareholders and (b) trying to squeeze more oil out of their existing projects. There may be a lot of new investment in the oil sands this year, but most of it will go into new equipment rather than new jobs.

The overall level of investment is also significantly lower than during the hiring boom of the 2000s and early-2010s, when many major projects were in their construction phase. There is no indication that the oil industry will ever again experience the investment and job growth of the previous boom years. Even oil boosters, like the International Energy Agency, acknowledge that oil is in “eventual decline in all scenarios.”

On the one hand, this change in oil industry behaviour is a victory for climate activists. The business case for large, long-term oil and gas projects is eroding as investors and governments around the world get serious about achieving net-zero emissions. If no new projects are built, it puts a de facto end date on extraction.

On the other hand, high prices are encouraging an intensification of existing projects to get as much oil out of the ground as possible before demand collapses. All that oil will be processed and burned somewhere in the world at exactly the moment when we should be moving away from fossil fuels altogether.

Ultimately, any incentive to produce more oil and gas is bad news for global emission reduction goals.

So what should governments be doing right now to ensure this latest oil boom doesn’t lead to a climate bust? Here are four suggestions.

Immediately cap oil production. It’s not enough to put a cap on production emissions from the oil and gas sector, as the federal government is considering. We also need to cap the absolute supply of crude oil before companies can scale up production. Just because Canadian oil and gas gets burned somewhere else doesn’t mean that we aren’t responsible for those emissions.

Set a timeline for phasing out oil and gas production altogether. Net zero by 2050 means zero oil and gas even sooner. The Alternative Federal Budget proposes a deadline of 2040 for the phase out of all fossil fuel production but, whenever the date, we need to provide workers, communities and investors with greater certainty about the inevitable wind down of the industry. There’s no doubt this will be a challenging and complicated task, but it is impossible to get started without a clear end goal.

Increase royalty rates. In the 1970s and 1980s, royalty payments accounted for a third of the oil industry’s expenditures. Now, only 10% of the industry’s cash goes to the public purse. Although higher oil prices will mean an increase in royalty revenues this year, it won’t be enough to make up for the pittance paid by oil companies during the previous downturn. The public should be the primary beneficiary of oil and gas extraction for as long as it is produced, especially given the enormous public costs imposed by oil extraction, starting with thousands of abandoned wells.

Invest in a just transition for workers. Most oil and gas workers would gladly transition into clean energy and other industries if they only had the opportunity. Public investment in skills training and green job creation is essential for smoothing the economic transition and building political support for the phase-out of fossil fuels.

A rebound in oil prices cannot only be a windfall for the oil industry and its shareholders. Through government leadership, we must ensure high oil prices today translate into green jobs and a clean economy tomorrow.

Thank you to Jim Stanford and Marc Lee for their comments on earlier drafts of this article.