When pandemic bubbles burst

The COVID-19 pandemic has both given and taken away so much from all of us. For some, the pandemic has literally taken away jobs and loved ones. But for others—depending on your view—it has given the opportunity to tighten social circles, deepen relationships and identify the people whom we really want to spend time with.

The downside of this, of course, is that it also makes our worlds smaller, both in person and online.

For the past two years, I’ve been able to pick and choose the people, discussions and values I surround myself with—the ones that give me energy and joy when there has been so little to go around. These people and discussions don’t exist in a vacuum, but every conversation was entered in good faith, debates were had, perspectives clarified and, ultimately, we were able to part ways—or end a FaceTime—feeling as though we had been intellectually stimulated in some way or another.

The downside of two years of this sort of social engagement is that we can end up forgetting what it is to exist outside of that bubble, to engage with those who may not be coming to a discussion in good faith, regardless of their political or person-al beliefs. On the Bad + Bitchy Podcast we talk about people, generally on the right and far-right of the political spectrum, who don’t engage in good faith conversations online and on TV—but still, we’ve experienced little of that during the pandemic.

At least, until recently.

On a recent trip to the United States, I found myself in a heated exchange with a friend whose political views are different from mine on the subject of Joe Rogan and cancel culture. (We won’t get into my views here, dear reader, so I’ll let you fill in that blank.) I can debate and have a tension-filled conversation about many topics—I have a podcast where I hone my arguments regularly—and I knew where I could make points and ask questions. However, that was never going to be the case. Instead, online culture has bled into interpersonal interactions and I was told I wasn’t a “free thinker” (I asked what the definition of that was, with no response). I was then aggressively questioned about what reality I live in when I said that Joe Rogan, with his Spotify deal worth at least $200 million, wasn’t, in fact, cancelled.

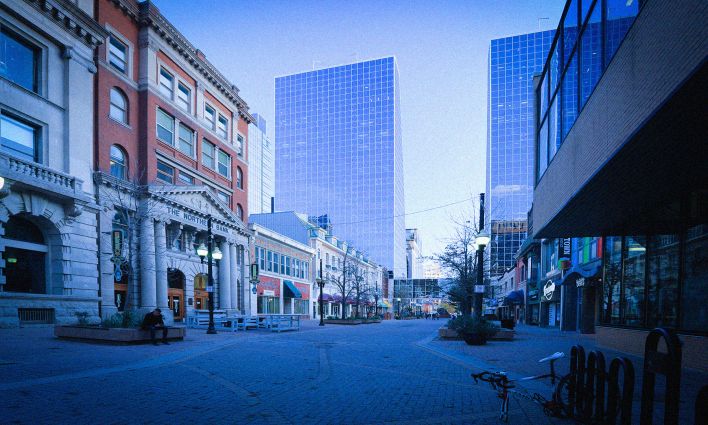

Bubbling up: Hate coalesces in Ottawa

This is one of the negative effects of the pandemic: too much time for people to spend alone in their homes being fed unchecked extreme political views, pushing people further into their political corners and developing herd mentality.

We saw the manifestation of this during the occupation: the Venn diagram of white supremacists, anti-vaxxers, accelerationists and anti-COVID-19 mandate protesters who found each other online and took to the streets of downtown Ottawa to have their voices heard.

With more people spending time at home and, by consequence, online during the pandemic, white supremacist groups were able to leverage this sudden increase in isolation (both physical and social) and loneliness to benefit themselves. In the early days of the pandemic and during subsequent lockdowns, people were stuck in their homes with little else to do but be online. It was only natural: we wanted the news, we wanted answers, the world felt scary and we experienced a loss of control. So we found solace and security where we could.

Unfortunately, in our isolated states, many of us needed and wanted to feel safe as the world outside our doors spiralled in unfamiliar ways. So we turned toward things that made us feel secure: like-minded people online. The problem, of course, is that the confirmation bias in these settings and digital algorithms are such that they continue feeding consumers more intensifying and radicalizing content. So, if someone right-leaning went online to find information about the pandemic, they could be fed progressively more radical content until they were, say, ingesting ivermectin or filming themselves harassing and assaulting people for following public health guidance—and the next thing you know, they’re watching videos on the Great Replacement, a white supremacist conspiracy theory.

Social media companies and other online spaces like to pretend that there are no real-world consequences to their platforms. The reality is that without them, the disparate individuals and groups who participated in the Ottawa Occupation and many other events before it, would likely never have found each other, leaving them and their extremist views on the fringes, instead of camped out with bouncy castles down the street from my old apartment.

The surprise reveal of two years spent at home...is that many people in our lives hold radical fringe views.

These online spaces have exacerbated herd mentality. Humans have always liked being around people who are similar to them. However, before the proliferation of the internet and social media, “people like us” was typically limited to the matching criteria of gender, race and class. But increasingly, we prioritize being surrounded by people who share the same political views, which explains how Randy Hillier, an Ontario Member of Provincial Parliament who’s earned a six-figure salary and pension for nearly 15 years, cavorting with and supporting individuals who make half that, at best.

In the lead up to the election of Donald Trump, and especially since, online herd mentality has led to toxic behaviours, such as the desire to “own the Libs” with quippy one-liners and bad faith arguments that cherry-pick and distort facts. Over the course of the pandemic, this acrimonious behaviour has transitioned offline, manifesting most violently as a marked increase in anti-Asian hate crime, with Vancouver being the new North American capital for these crimes.

Coupled with this increasingly important need to surround ourselves with like-minded people, this “own the Libs” mentality has drastically and negatively impacted our ability to engage in healthy conflict, as was the case on my recent trip. In addition to being aggressively questioned, another friend party to the incident quipped, “I didn’t know this would trigger you.” Trying to engage in a discussion where your thoughts are simultaneously being ignored and requested, while also being yelled over isn’t “triggering.” It’s antagonizing.

People are capable of well-intentioned discussions. However, they need to be given the space to explain themselves and be open to either being wrong or content with disagreement. Conflict is healthy, but unfortunately we are now quick to blame, take offence when none is meant and close ourselves off to the ideas of others (despite being “free thinkers”). This is not only due to herd mentality, but also the increasingly fractured media ecosystem where one side is given a certain set of “facts” different from the other and arguably divorced from reality. If we cannot agree on whether the sky is blue—or if we are still living through a pandemic—we can say goodbye to healthy conflict and debate, both of which are integral to the furthering of democracy. However, it’s worth pointing out that there are some topics where debate is undeserving as the subject matter too abhorrent to entertain, even as an intellectual exercise, namely the subjects of Nazis and white supremacy.

The surprise reveal of the past two years spent at home perfecting our sourdough starters, learning to make cocktails and knitting is that many people in our lives hold radical fringe views. Whether it’s posting COVID-19 conspiracy theories or racist rhetoric (e.g. anti-Asian sentiments, anti-Black sentiments during the summer of 2020), we’ve learned to either exorcise these people (and views) from our lives or tacitly agree to ignore. However, what the Ottawa Occupation showed us is that we all have limits, which for many of us were a combination of either aligning with a Nazi-supported movement, or not caring that they were aligned with a Nazi-supported movement.

Seeing friends and acquaintances support the occupation resulted in many Ottawans evaluating and ending relationships that had maybe outgrown their relevance or that they had previously ignored. The occupation of their neighbourhoods and support (tacit or outright) of Nazis, blatant white supremacists, and seditionists was too much. We now know who among our family, friends, colleagues, and neighbours supported the occupiers. This is a scary thought for any racialized person living in Ottawa, having to constantly question whether your hair stylist, massage therapist, or date supported the occupation and may openly or quietly believe that their whiteness trumps your humanity.

It’s these concerns that lead to racialized people having anxiety and other mental health issues. For white people who experienced psychological torture and violence during the occupation, they may continue to experience adverse mental health effects, but there is clear distinction between the experiences of white and non-white individuals when it comes to white supremacy, particularly as racialized people in my life were doxxed and had to leave their houses during the occupation. The fear and anxiety that white people felt over those four weeks is a sliver of what their racialized neighbours faced then and continue to face today.

The question is, where do we go from here? The Pandora’s box of white supremacy in Canada has been opened. How do we get the lid back on, and whose job is it to make sure it’s closed?

Header image photo credit: Michael Swan