Despite being billed as the world’s “last best hope” to halt climate change, the highly anticipated 26th UN climate conference concluded last Sunday without the kind of ambitious global agreement scientists and activists were demanding.

Instead, we got a deal—the Glasgow Climate Pact—that makes modest but insufficient progress toward the urgent decarbonization of the global economy. As Équiterre’s Émile Boisseau-Bouvier put it, “this COP [Conference of the Parties], without saying that it was a failure on all fronts, can certainly not be called a success.”

So what, if anything, was agreed to at COP26? What role did Canada play on the world stage? And what comes next for domestic climate policy? Here’s your post-COP summary.

Wasting time we don’t have

The Glasgow Climate Pact, which was signed by 197 countries, is most notable for naming coal power and fossil fuel subsidies as targets for global climate action. This is more direct language than in past international climate agreements.

Unfortunately, there are some big caveats. The final text only commits to the “phase-down” of "unabated” coal power, which provides two serious and distinct loopholes for continued use of coal. Similarly, the text only names “inefficient” fossil fuel subsidies as a problem, a qualifier for which there is no agreed definition. At best, this language lays the groundwork for a more tangible deal on fossil fuels at future COP summits.

A separate agreement was reached on implementing Article 6 of the Paris Agreement to create a global carbon trading market. Carbon trading is useful in theory, but in practice risks shifting pollution from one country to another without a meaningful net reduction in emissions.

Many individual countries also tabled new national climate targets during the conference but, taken together, these new commitments fall well short of consistency with the Paris Agreement target of limiting global warming to no more than 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. Even if all of the new targets are achieved—a big if given countries’ poor historical records on meeting climate commitments—the world is still on track for 2.4°C of warming by the end of the century.

For its part, Canada’s signing of the Glasgow Pact makes little practical difference because the Canadian government has already made similar commitments domestically. Likewise for the Just Transition Declaration that Canada signed with 13 other countries, which is a statement of principles that aligns with the government’s pre-existing understanding of a just transition.

The devastating floods in British Columbia this week, which follow on the heels of rampant wildfires only a few months ago, are only the most recent harbingers of the costs of inaction.

Where Canada could have shown real leadership—in supporting the developing countries that are least responsible for climate change yet most affected by its consequences, for example, or championing a global oil and gas phase-out—Canada instead settled for the status quo.

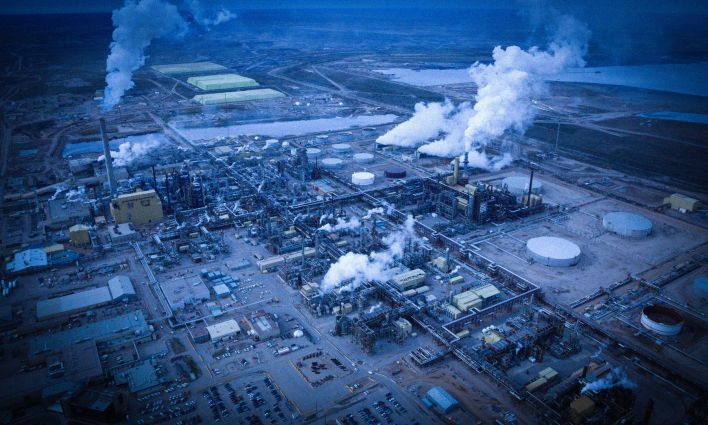

In sum, Glasgow was a punt for an international community still largely unwilling to make the difficult but necessary choice to move away from fossil fuels—especially those wealthy fossil fuel producers in the Global North, such as Canada, that have the power to unilaterally curtail oil and gas extraction.

Glasgow could have had a worse outcome, but it wasted time we don’t have.

All eyes on oil and gas

Now the Canadian government must pivot from its lofty rhetoric on the international stage to the practical pursuit of domestic climate action. Two crucial policies loom on the horizon.

First, the government must deliver on its now-legislated requirement to produce a new climate plan by the end of 2021. The government did publish a plan as recently as December 2020, but that document was based on Canada’s old climate target of a 30% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions below 2005 levels by 2030. The new plan must be consistent with the new target of a 40% reduction.

All eyes will be on the oil and gas emissions cap promised by the Liberals during the recent election. If the government implements a hard and declining cap on absolute oil and gas sector emissions, it could be a breakthrough policy for winding down the sector. On the other hand, a weak cap designed to reduce emissions intensity could have the perverse effect of incentivizing new production.

The second big policy is just transition legislation, which the Liberals first promised during the 2019 election and reiterated during this year’s campaign. Consultations toward a “people-centred just transition” began in the summer but were put on hold during the election. In its consultation document, Natural Resources Canada failed to even acknowledge the fossil fuel industry. It remains to be seen how, in practice, Canada intends to support a just transition of the oil and gas sector moving forward.

Of course, there is a lot more the federal government could also be doing. The devastating floods in British Columbia this week, which follow on the heels of rampant wildfires only a few months ago, are only the most recent harbingers of the costs of inaction.

As the new Alternative Federal Budget explains, the Canadian government must take a “hands-on approach to transitioning the economy away from the production and consumption of fossil fuels.” It’s time they got to work.