The decades after the French Revolution were tumultuous in Paris. Every few years, it seemed, the popular classes, made up of the poor and oppressed people, were rising up and overthrowing whatever the latest iteration of the French government was. Through the fall of the monarchy, the reign of terror, the rise of Napoleon, the restoration of the monarchy, and three revolutions, there was one constant—Paris was ungovernable.

For revolutionaries in Paris, there was no more iconic symbol of resistance than the barricade. The city—like most European cities—was a winding maze of narrow streets and alleys, built up over centuries of slow and organic urbanization. For the revolutionaries, who knew the terrain well, it was simple to outmaneuver the authorities in such an environment—sequestering troops into small zones using barricaded streets while revolutionaries took key infrastructure.

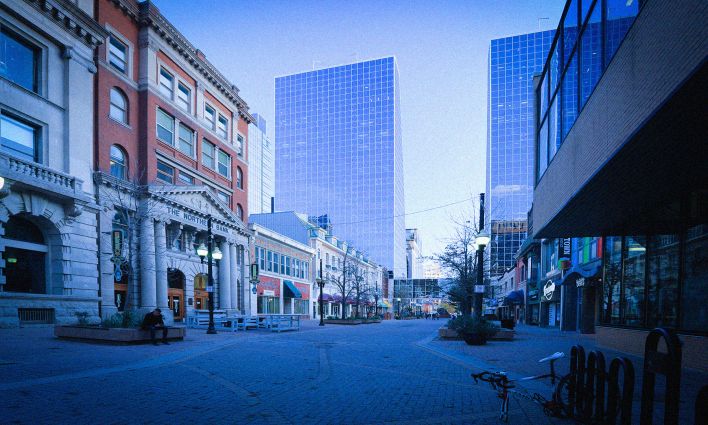

Today, Paris looks very different. While many of the continent’s cities retain their narrow, winding, medieval streets, Paris today has long, wide, and straight boulevards that crisscross the central city, including through its oldest areas. Such boulevards are iconic—they are, for many people, the defining feature of Paris’ urban landscape. They can be traced back to the work of one man—Georges-Eugène Haussmann.

Over two decades, Haussman—who governed the Seine administrative region, which encompassed Paris and its immediate suburbs—knocked down over 12,000 “slum” buildings in the central city. He designed and oversaw the construction of iconic buildings, such as the national opera house, major parks across the city, and a modern sewage system. His imprint rests on boulevards like Sebastopol—whose width and long sight lines facilitated troop movements when the quartiers populaires got restless.

It was, in Haussman’s own words, the “gutting of old Paris, of the quarter of riots and barricades.” The army brutally crushed the next uprising in Paris—the 1871 Paris Commune— killing thousands after taking the city via Haussman’s boulevards.

Cities on FIRE

The “renovation” of Paris is an extreme and early example of a persistent phenomenon: cities are always changing, and those changes are a reflection of—and a contributor to—the balance of power among contending social forces.

Today, in Global North countries like Canada, “global cities” are some of the most important nodes in the global network of capital circulation and accumulation—and the undisputed king of capital in cities is real estate.

A 2017 UN report pegged global real estate value as being worth $217 trillion USD—that is 36 times the value of all the gold ever mined. Three quarters of that is in housing, the majority of which is in cities. That number has almost certainly ballooned in the post-COVID real estate boom. Land, especially city land, is one of the most important asset classes in a world where everything is an asset.

In Urban Warfare, former national secretary of urban programs at the Brazilian Ministry of Cities, Raquel Rolnik, describes the shift towards financialization of home ownership as being “asset-based welfare” and “privatized Keynesianism” that emerged alongside 1980s and 1990s neoliberal restructuring.

In the context of aging populations, assaults on public services, and the retreat of the welfare state, Rolnik writes, “the use of homeownership as a wealth stock, its valorisation over time and possible monetization worked, in practical terms, as potential substitutes for public pension and retirement systems.”

If home ownership was going to become the ticket to retirement, then the value of homes—like all financial assets—needed to constantly grow. Governments across the Global North, including in Canada, began to scrap programs that exerted a downward pressure on the cost of homes.

In its heyday in the mid-late 1960s, nearly 10 per cent of all new housing construction in Canada was low-income public housing constructed by the federal government. From the 1970s to the mid-1980s, the feds pivoted to a model based on coops and non-profit housing, financing a similarly high level of construction. Brian Mulroney’s Conservatives slashed that budget—leaving the question of social housing to the provinces—and then Jean Chretien’s Liberals destroyed it. By the mid-1990s, new social housing was mostly gone, with some variation between provinces.

But the shift towards financialization of housing took place in the context of another shift that radically restructured cities in the Global North in the late 20th century: deindustrialization.

The explosive growth of cities in the 19th and 20th centuries is deeply and inextricably linked to industrialization. Industrial capital—factories, warehouses, plants—was a core element of modern city-making. When it left in search of cheaper labour overseas, or cheaper land in the exurban periphery, it fundamentally altered the cities it left behind.

Geographer Samuel Stein, in Capital City, describes how industrial capital and real estate capital have different relationships to land. While industrial capital views land as an expense, real estate capital views it as an asset. Industrial capital, then, aims to reduce the cost of land, while real estate capital aims to increase it.

This type of conflict between different capitalist factions meant that during the era of industrial cities, there was another source of downward pressure on real estate values—one coming from within capital itself. Major industrialists in cities had direct, material interest in keeping land cheap—both because it would directly bring down their operating costs, and also because access to cheaper housing meant less pressure from organized workers for wage increases.

When heavy industry migrated from central cities, that pressure evaporated. Suddenly, the only real game in town was FIRE—finance, insurance, real estate—as well low-wage service sectors.

FIRE sector dominance has far-reaching implications for the organization of cities today. Not all of it is negative—stricter environmental rules, in addition to being hard-fought and won by local organizing, are also well within the agenda of real estate capital, since pollution tends to bring down property values.

It has also created a set of perverse incentives around positive planning developments inside cities. Real neighbourhood improvements—such as safer streets, improved air quality, better schools, and so on—mean increased property values, which mean increased displacement for the people lower on the ladder.

“As some places endure land market inflation, others fall prey to disinvestment,” Stein writes, “their land loses its exchange value, their residents are shut out of credit markets, and their buildings fall into dangerous disrepair… Gentrification cannot be a universal phenomenon; money tends to come from one place and go to another, creating chaos on both ends.”

The right to the city

Of course, capital is not the only social force at work in cities. Cities are also home to dynamic and popular social movements that confront the different segments of capital in a constant push and pull over who gets to decide who the city serves.

Revolutionary theorists have long viewed cities as the birthplace of socialist movements. Friedrich Engels, in The Condition of the Working Class in England, wrote that urbanization was equally important to industrialization in the formation of the working class.

“If the centralization of population stimulates and develops the property-holding class, it forces the development of the workers yet more rapidly… The great cities are the birthplace of labour movements, in them, the workers first begin to reflect upon their own condition, and to struggle against it; in them, the opposition between proletariat and bourgeoisie first made itself manifest… without the great cities and their forcing influence upon popular intelligence, the working class would be far less advanced than it is.”

Cities were, during the industrial era, central nodes of working-class power. In North American industrial cities like Milwaukee, socialists in local government dramatically improved public infrastructure in working-class communities. North American “sewer socialism,” as it came to be known, was an important force in the Great Lakes region until the era of deindustrialization.

The most ambitious experiments happened in Europe. In European cities like Vienna, socialist city governments embarked on massive construction of social housing. In “Red Vienna,” the socialist municipal government constructed a massive amount of public housing in a short period of time. Today, nearly a quarter of all the housing in Vienna is publicly owned, and nearly another quarter is cooperative or privately managed low-income housing. Vienna is one of the most affordable major cities in the world.

Industrial cities also were sites of some of the most important labour organizing experiments during the early years of the workers’ movement. Before the widespread adoption of industrial unionism in the 1930s, city-level labour federations acted as coordinating bodies during major strikes, such as the Seattle general strike in 1919, which saw workers take over the administration of key public services—as well as the Winnipeg general strike in 1919, a watershed moment in Canadian labour history.

Deindustrialization proved to be its own battleground for urban social movements. In cities, social conflict is often a literal question of space—when a former factory or warehouse shuts down, what will happen to that land? Will it become social housing, a park, a luxury condo tower, or a contaminated, dilapidated mess?

In Montreal, the decommissioned railcar factory in the Angus Yards was the subject of a long fight in the 1980s. Organized tenants managed to win a significant percentage of social housing. The area remains relatively affordable.

The Lachine Canal zone, on the other hand, was a loss—developers gained the upper hand and converted the buildings along the canal into expensive condos, in a reflection of the growing power of FIRE capital. A similar battle might be brewing over downtown skyscrapers, as post-COVID remote work entrenches and commercial real estate deals with persistently high vacancy rates.

Tenant organizing, in particular, has grown rapidly in the post-industrial city and serves as an important counterweight to FIRE capital. Much as labour unions fought—and continue to fight—for workers against their bosses, tenants’ organizations fight against landlords and developers. The past years in Canada have seen an important revival of the tactic of rent strikes—tenants withholding their rent from landlords in an effort to negotiate on specific issues, such as repairs or rent increases.

Migrants are fighting to access city services, disabled people are trying to make accessible infrastructure, racialized communities are fighting against police violence, women are fighting against street harassment.

Together, these movements are all advocating for a common cause: “the right to the city,” a concept coined by French urban theorist Henri Lefebvre—a right which “can only be formulated as a transformed and renewed right to urban life,” he wrote.

“The right to the city is far more than the individual liberty to access urban resources,” writes geographer David Harvey. “It is a right to change ourselves by changing the city. It is, moreover, a common rather than an individual right, since this transformation inevitably depends upon the exercise of a collective power to reshape the processes of urbanization.”

The balance of power

Cities are a material consequence of policy—their form is the concrete manifestation of the words that politicians write into legislation. In their current form, cities are monuments to the deeply unequal political and economic system under which we live.

“Urban segregation is not a frozen status quo, but rather a ceaseless social war in which the state intervenes regularly in the name of ‘progress,’ ‘beautification,’ and even ‘social justice for the poor’ to redraw spatial boundaries to the advantage of landowners, foreign investors, elite homeowners, and middle-class commuters,” urban historian Mike Davis writes in Planet of Slums.

“As in 1860s Paris under the fanatical reign of Baron Haussman, urban redevelopment still strives to simultaneously maximize private profit and social control.”

The World Bank estimates that, by 2050, over 70 per cent of the global population will live in cities. Whether or not those cities are inclusive, democratic, and accessible will be a defining question for a future that will already be wracked by climate change.

Cities both reflect and reify the balance of power. The actions we take inside our cities today will—literally—set the terrain for the struggles in the decades to come. Will our cities become police-patrolled walled gardens for the rich ringed by slums for the poor, or will they be spaces of equality and participation? Who does the city belong to?

“The cornerstone of the low-carbon city, far more than any particular green design or technology, is the priority given to public affluence over private wealth,” Mike Davis writes in Who Will Build the Ark? “The ecological genius of the city remains a vast, largely hidden power. There is no shortage of planetary “carrying capacity” if we are willing to make democratic public space, rather than modular, private consumption, the engine of sustainable equality.”

The fight over the city is already on—it’s up to all of us to choose which side we’re on.