At the end of May, Global Affairs Canada began consulting Canadians on priorities for a future Canada-Africa Economic Cooperation Strategy. The trade-centric effort—an agenda item from Minister Mary Ng’s 2021 mandate letter from the Prime Minister—is distinct from a separate Africa framework that Liberal MP Robert Oliphant has been stickhandling for Foreign Affairs Minister Mélanie Joly for the past two years. Both projects respond to criticism that Canada has neglected relations with Africa as the continent’s economic clout and geopolitical importance grows.

Oliphant has pointed out that in developing any new Africa strategy, Canada wants to avoid “anything that even suggests or hints at neocolonialism.” If this is true, the government should find ways to terminate or rework its overtly neocolonialist investment treaties on the continent. Leaving the treaties in place will frustrate the chances that African nations will see social benefits from today’s infrastructure and “critical resource” boom. It would also maintain a double-standard with respect “rules-base” trade—one that puts African nations at a significant disadvantage.

Between 2008 and 2015, Canada launched investment treaty negotiations with 18 African nations. Eight of these negotiations resulted in operational Foreign Investment Promotion and Protection Agreements, or FIPAs (Table 1), while the remainder stalled at various stages (Table 2). All the FIPAs include a controversial investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) process that is losing favour internationally due to the drag it creates for sustainable development, responsible climate policy, and human rights.

While the preambles of these Canadian investment treaties sometimes recognize the desire of both parties to promote sustainable development, the Conservative government of the day saw them mainly as a tool of “economic diplomacy—a foreign policy shift emphasizing Canadian trade priorities over social outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. This might explain why the FIPAs reflect Canada’s model investment treaty language over more moderate, balanced models developed in Africa.

Canada has a history of supporting repressive regimes in Africa when it benefited powerful corporate interests, and a reputation for ignoring human rights violations or poor environmental performance by Canadian mining companies around the world. “Economic diplomacy” rationalized this foreign policy stance by insisting that “all diplomatic assets [should be] marshalled on behalf of the private sector in order to achieve the stated objectives within key foreign markets.”

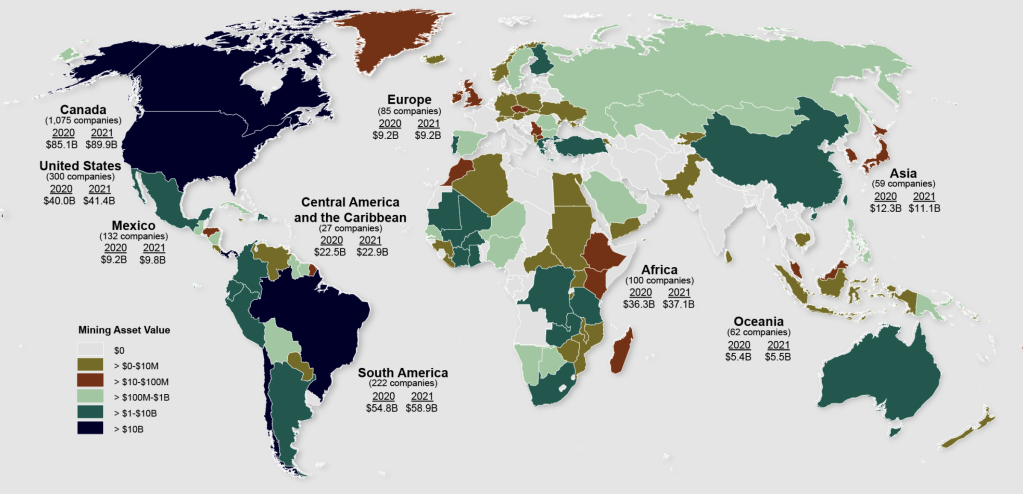

As a result of this early trade-centric policy, Canada’s FIPAs with African nations serve mainly to protect Canadian mining investment (estimated at $36.5 billion across the continent in 2020) against the developmentalist or democratic impulses of governments. They do so by enforcing a colonial-style legal relationship wherein Canadian investors may challenge changes to mining laws or regulations, or delays to production, as violations of international law before private investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) tribunals rather than in domestic courts.

While courts will sometimes consider the interests of other affected groups in a dispute, such as Indigenous communities contesting unwanted resource development, investment tribunals are under no obligation to do so. Nothing in Canada’s FIPAs provides additional powers or leverage for states to pursue corporations that fail to meet their legal obligations, whether to employees, environmental protection, or worker health and safety that might counterbalance the privileges afforded by ISDS.

Though there have been few known African FIPA disputes to date, research by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has shown that Canadian investors in the mining, oil and gas industries are behind 70% of Canadian ISDS cases outside North America. Two Canadian firms, Winshear Gold and Montero Mining, are among a half-dozen international companies suing Tanzania for hundreds of millions of dollars in compensation for changes to the country’s mining laws aimed at getting a better deal from resource exploitation.

The double-standard arises from recent steps by rich countries to withdraw from investment treaties that include ISDS. Canada did not consent to ISDS in the renegotiated Canada-U.S.-Mexico Agreement, since this protected the government’s right to regulate for environmental, health, and other reasons. In July, the European Commission announced that Europe would withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty, the world’s most-used ISDS system for energy-related disputes, since it “is no longer compatible with the EU’s enhanced climate ambition under the European Green Deal and the Paris Agreement.”

The Trade and Investment Research Project contributed to the Global Affairs consultation in a joint submission with l’Association québécoise des organismes de cooperation internationale, Réseau Québécois pour un mondialisation inclusive, and Regroupement pour la responsabilité sociale des entreprises. The submission made seven recommendations for prioritizing human rights, working conditions and livelihoods, and the environmental impact of foreign investment in the new strategy, with an emphasis on holding corporations accountable for labour and human rights violations in their supply chains.

Ideally, Canada’s outdated, neocolonialist FIPAs in Africa should be terminated so that African nations can enjoy the same freedom to regulate foreign investment as Canada and the EU are carving out for themselves. South Africa began unilaterally terminating its bilateral investment treaties in 2012 after an internal review found they were incompatible with the country’s development priorities. Tanzania has given notice to terminate its 2013 FIPA with Canada, as it did a few years ago with its Dutch investment treaty, since Tanzanian law currently requires mining-related disputes to be adjudicated domestically.

Alternatively, Canada could agree to replace the current FIPAs with investment frameworks developed in Africa, which do a far better job balancing investor protections and governments’ right to regulate foreign investment. For example, several African model treaties, including one developed by the East African Community, avoid broad “fair and equitable treatment” provisions, add binding obligations for investors (and the option for states to file counterclaims for violations of those obligations), and force disputes through the courts or state-to-state dispute settlement rather than ISDS.

Ultimately, whatever approach the government takes in its new Africa strategy, it should be free of both neocolonialism and break definitively with “economic diplomacy”—Canada’s tendency to act on behalf of domestic corporate interests rather than the sustainable development needs of international partner nations.