With roughly $62 billion in new climate-related spending over the next decade, the federal government’s 2023 budget doubled down on climate action with a focus on investment in the clean economy.

However, the budget locks in a particular approach to climate action—one where incentives to the private sector do the heavy lifting of growing green industries. More than $56 billion in this budget is allocated to investment tax credits and other subsidies to encourage the market to invest in strategic sectors. When past budgets are included, the total value of federal “clean” tax breaks rises to $81 billion over the next decade.

It’s a big and risky bet on the private sector to take the wheel on climate action, with little in the way of backup plans should the market balk. Some of these new incentives even include generous subsidies to Canada’s fossil fuel industry.

Investment tax credits: a mixed bag of competitive climate policies and bad fossil fuel subsidies

Investment tax credits (ITCs) allow corporations to deduct some of the cost of eligible investments from their taxes. By reducing the cost of investing in clean technologies, ITCs can encourage productive private spending on the clean economy. However, unlike direct public spending, ITCs do not guarantee that those investments will be made at all.

As of Budget 2023, Canada now offers climate-related investment tax credits for (1) clean electricity, (2) clean technology manufacturing, (3) clean technology adoption, (4) clean hydrogen production and (5) carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS). All of these credits are refundable at rates of between 15 and 40 per cent.

Notably for workers, labour conditions are attached to several of the investment tax credits. To receive the full value, firms must pay workers at least the prevailing wage and allocate at least 10 per cent of hours worked by tradespeople to apprentices. These conditions could be stronger, especially in terms of diversifying the trades with more representation from equity-seeking groups, but they establish an important precedent for future policy.

The Investment Tax Credit for Clean Electricity is the largest of the five programs at an expected cost of $25.7 billion over ten years. Non-taxable entities such as Crown corporations and corporations owned by Indigenous communities can claim the credit, which is especially important in a context where the majority of the electricity system in Canada is owned and operated by public utilities (Alberta being an important exception). While a 15 per cent credit is not game changing, it is likely to tip the cost-benefit scale in favour of crucial investments in smart grids and (potentially) interprovincial electricity transmission that are otherwise uncompetitive.

The ultimate effectiveness of this measure will hinge in part on the forthcoming federal clean electricity regulations. An ambitious timeline for a 100 per cent clean grid would require the rapid phase-out of gas-fired power and a commensurate push for renewable power. Less ambitious regulations, including loopholes for carbon capture and storage, would permit gas to play a larger role than it should for some provinces.

The clean technology credits—$11.1 billion for manufacturing and $6.9 billion for adoption—are offered at a rate of 30 per cent and cover a wide range of upstream and downstream activities, from critical mineral mining to auto assembly to geothermal systems. These tax credits are likely to make a positive difference, especially in terms of competing for investment with the U.S. and its new incentives under the Inflation Reduction Act.

So far, so good. But the next two incentives are shakier.

First, the $17.7 billion Investment Tax Credit for Clean Hydrogen explicitly includes “blue” hydrogen produced using natural gas. While the credit does employ a sliding scale that encourages cleaner production—more emissions-intensive hydrogen is only eligible for a 15 per cent credit compared to 40 per cent for green hydrogen—the bottom line is that this tax credit incentivizes the continued extraction and combustion of fossil fuels. While there will be niche applications where green hydrogen may play a role, such as in heavy transport, the case for hydrogen as a climate solution is tenuous, especially when better options are already available.

Second, the Carbon Capture, Utilization, and Storage (CCUS) Investment Tax Credit is a direct subsidy to a fossil fuel industry that made record profits in 2022. Among other problems, CCUS is very costly, has not been proven to work at scale, and perpetuates the economy’s dependence on fossil fuels instead of taking steps toward phase-out. Topped up in this budget to a total value of $18.1 billion over the next decade, the CCUS tax credit is an enormous handout to major fossil fuel producers and consumers that will, at best, lead to considerable stranded assets in the coming decades and, at worst, directly undermine Canada’s broader transition away from fossil fuels. The tax credit means the federal government will be publicly subsidizing the inevitable cost overruns we are likely to see from uneconomic CCUS projects.

Odds and ends

There is some direct climate program spending in this budget. Most importantly, the government commits $3 billion for electricity projects and $1.6 billion for a previously-announced National Adaptation Strategy. There are smaller amounts for VIA Rail operations, natural disaster responses and making heat pumps more affordable.

The Canada Infrastructure Bank (CIB) is given a new electricity-focused mandate in this budget. It will commit $20 billion of previously-budgeted money to clean electricity and green infrastructure projects. Since that money comes in the form of loans to the private sector, the government expects to eventually recoup the full cost with no net impact on their bottom line.

In general, the electricity focus in this budget is important because decarbonizing the grid is crucial for enabling electrification of other sectors. Without sufficient clean electricity generation, we can’t make the most of climate-friendly technologies such as heat pumps and zero-emission vehicles. And without sufficient electricity transmission, we will have a hard time managing a network of largely decentralized, intermittent renewable power.

The budget also released new details about the $15 billion Canada Growth Fund announced last year. The fund will be managed by the Public Sector Pension Investment Board with a mandate to attract private capital to the clean economy. It’s a vague and uninspired plan to offload decision-making to the private sector, especially given the historical failure of the CIB to do exactly the same thing. Without attaching stringent green strings to its spending, it also runs the risk of becoming an additional pool of public capital available to subsidize CCUS and the oil and gas sector.

Adding it all up

As is typical of recent federal budgets, most of the $62.1 billion in climate-related spending announced in this budget is backloaded. We only count $20.7 billion being spent over the next five years. Of that figure, $17 billion or 82 per cent is for investment tax credits. Only $1.4 billion or seven per cent is for direct emissions reductions.

When all previously-announced climate spending is included, we expect the federal government will spend $15.2 billion on climate action in this fiscal year (2023/24), rising to $19.9 billion by 2027/28. That amounts to about 0.5 per cent of GDP this year rising to 0.6 per cent of GDP over the next five years.

Those figures include what we identify as “fossil-friendly” spending, such as the carbon capture tax credit and Net-Zero Accelerator, both of which subsidize the fossil fuel industry. Those fossil-friendly items account for about $2 billion or 14 per cent of climate-related spending this year.

In sum, while Budget 2023 does move Canada closer toward the two per cent of GDP target, we are still spending at only a fraction of that level. Subsequent budgets will need to match the ambition of this budget—with new, annual spends in the range of $50-100 billion—to close the rest of the gap and invest at the speed and scale that the climate crisis requires.

Tax credits alone won’t transition to net-zero

Incentives to the private sector have always been a component of the federal government’s approach. Between the new investment tax credits and the public financing of private projects, however, Budget 2023 goes all in on these market-led climate solutions. As one senior official summarized during the budget lockup, “decision making remains in the market, where it should be, because that’s where the expertise is.”

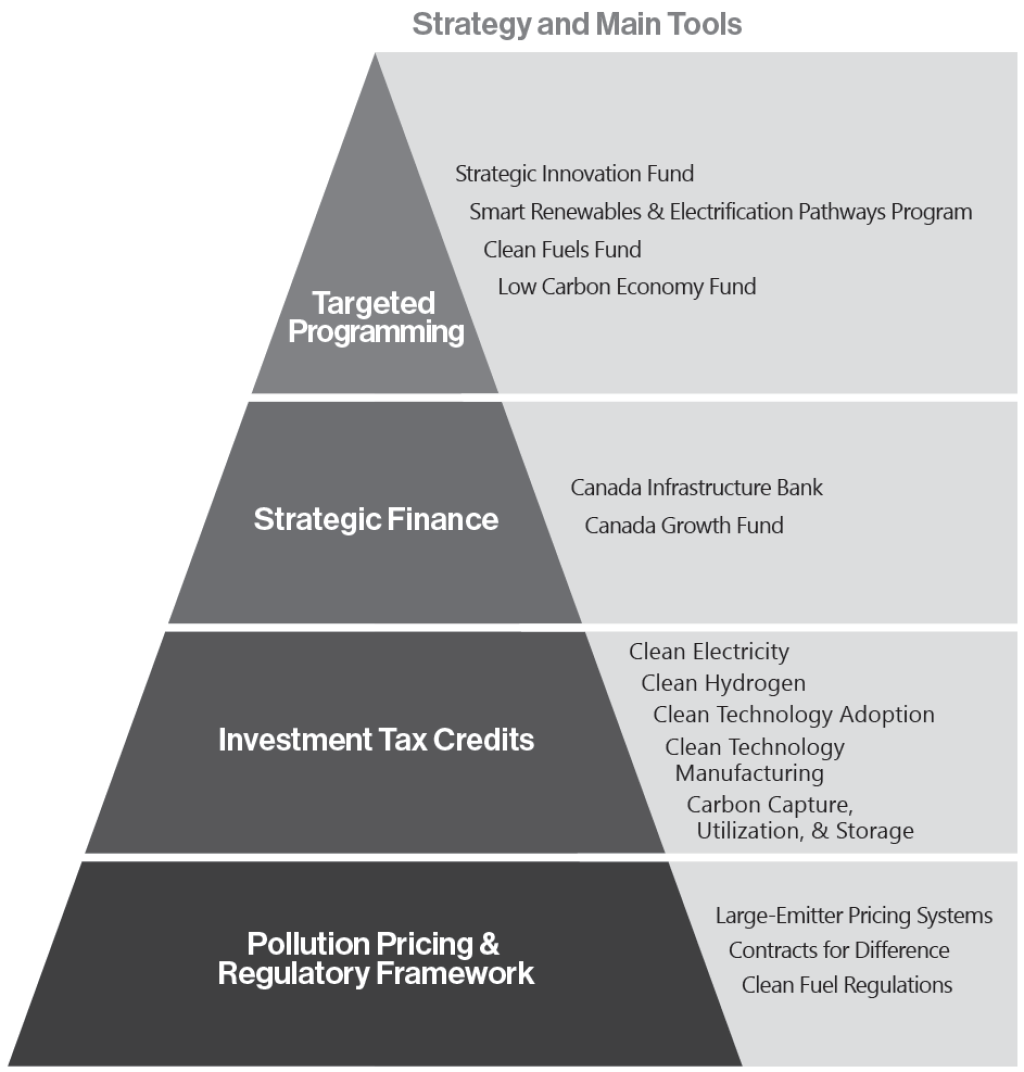

A pyramid diagram in the budget lays out the strategy very clearly. At the bottom of the pyramid is the regulatory framework that is intended to broadly shape market decisions. Many key elements of this framework are currently in development, including a cap on oil and gas sector emissions, a clean electricity standard and a zero-emissions vehicles standard. These regulations will need to be ambitious and comprehensive to lay a solid foundation for the rest of the strategy. On top of that foundation are the suite of investment tax credits introduced over the past year and discussed above. Next comes strategic finance to the private sector and other levels of government. These are largely loans that the government expects will be paid back. The final layer—the tip of the pyramid—is direct public spending, which is made up of limited, targeted investments in bespoke projects.

This strategy may work in theory. Consider the electricity investment tax credit. If that 15 per cent subsidy ends up costing the projected $25.7 billion, that will mean at least $170 billion has been invested by the market in clean electricity. That’s excellent bang-for-public-buck.

There are a few problems, though. First, we don’t know to what extent corporate Canada and public electricity utilities will step up with the billions of dollars of investment the government is counting on. Given the urgency of the climate crisis and the necessity of early action to meet our long-term targets, a wait-and-see approach is extremely risky. Most of the investment tax credits don’t even kick in until 2024.

Second, there are key projects in the national interest that the market alone is unlikely to ever take on—or at least to get done quickly—no matter how generous the tax incentive. Interprovincial electricity transmission infrastructure—such as the Atlantic Loop to connect Atlantic Canada and Quebec—is vital even if the costs are never directly recouped. Some of these projects have price tags far larger than the government’s apparent appetite for targeted programming.

Third, even if the market spends at the necessary level, there is a risk that these tax credits subsidize corporate spending that was going to occur anyway. That’s a waste of money that could be much better spent on a public purpose. This will also be the case for more generous investment tax credits than would have been required to induce the investment (say a 40 per cent credit when only 15 per cent would have been necessary).

Fourth, despite the welcome inclusion of labour conditions on some of this budget’s tax credits, leaving decision-making to the market fails to address crucial issues of equity and regional development. Whereas the public sector can target new infrastructure in struggling areas while emphasizing diverse hiring and community benefits, the private sector will spend wherever and however it is likely to make the greatest profit. A Just Transition requires balancing social with economic priorities.

Finally, an incentives-driven approach leans too heavily on carrots and not enough on sticks. The reality of the climate crisis is that we must not only scale up the new clean economy but also wind down the old fossil fuel economy. Between the government’s support for CCUS and blue hydrogen and its continued enthusiasm for the production of fossil fuels for export, this budget offers few assurances that Canada is serious about tackling the root cause of the climate problem.

To be fair, there are sticks in the government's tool box. The carbon pricing system is slated to rise to $170 per tonne by 2030, which will help to shrink the gap between the current price and the updated estimates for the social cost of carbon (i.e., the actual cost of each tonne of emissions) put forward a few weeks ago. An oil and gas sector emissions cap is in development. We are also expecting a national clean electricity standard, a zero-emissions vehicle mandate and sustainable jobs legislation. Together, these five policies have the potential to drive deep emissions reductions in the economy.

Unfortunately, the oil and gas industry is paying very low effective carbon tax rates through the Output Based Pricing System for large emitters. In addition, the fossil fuel industry is lobbying to ensure the oil and gas emissions cap will not place any restrictions on the actual amount of oil and gas produced and to ensure there are loopholes for natural gas in the clean electricity standard. The fight over these regulations could make-or-break the government’s entire approach to emissions reductions.

In sum, the combination of a hands-off investment approach and an uncertain regulatory framework raises doubts about Canada’s climate strategy moving forward. A greater emphasis on public spending paired with a stronger regulatory wind down of fossil fuels would put Canada in a better position to decarbonize the economy.

Crucial areas left out of the plan

Budget 2023 fails to make meaningful investments in public transit and low-income housing efficiency, which are both key to a safer, more affordable and healthier future for Canadians. And at a time when the world is facing increasing geopolitical tensions, the budget lacks new investments in global climate action while making substantial cuts to international assistance more generally.

Indigenous-led climate solutions are largely absent from the budget. Indeed, when it comes to reconciliation, the budget “failed at every turn,” according to Indigenous critics.

The budget also sidesteps investments in a Just Transition for workers and communities across the country. The recent Sustainable Jobs Plan did not inspire confidence that this budget would deliver new programs for workers, but the fact remains that support will be needed to protect livelihoods, ramp up skills training and diversify communities as Canada moves away from fossil fuels.

What comes next?

When it comes to climate spending, getting the scale right is half the battle. On that front, Budget 2023 is a win for climate advocates. If every budget were this ambitious, we would be well on our way to spending the two per cent of GDP necessary to decarbonize the Canadian economy.

The Canadian government’s preference for tax credits and financing instead of direct public spending means we will have to wait and see if the market steps up. Projects of vital national importance may be left in limbo if private investors do not view them as profitable enough. And even if the market delivers on all the green infrastructure we need, there are outstanding questions about whether those investments will advance environmental, social and regional priorities and whether those investments would have been made anyway without public money padding corporate profits.

We are at a convergence of crises, with climate catastrophe being compounded by rising levels of economic and social inequality, rising geopolitical tension and the destructive legacies of colonialism. The fight against climate change—if it is to tackle the morbid symptoms of the crises it interlocks with—requires public investment.

As economist Mariana Mazzucato says, “the global transition to a net zero economy will not happen at the pace that is needed unless states embrace their proper role as market maker and investor in public goods.” Budget 2023 is a step up from previous federal budgets, but we are still waiting on the federal government to embrace that role.