The following text is a transcript of a speech given by Armine Yalnizyan, Atkinson Fellow On The Future Of Workers and former senior economist at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, to the Canadian Economics Association at Toronto Metropolitan University on May 31, 2024. Yalnizyan was accepting the Galbraith Prize in Economics, an award for lifetime achievement in advancing progressive economics in service of building a fairer economy. This text was first published by Progressive Economics Forum.

Thank you for the immense honour of being awarded the Galbraith Prize in Economics—and for agreeing to wait a year to hear this speech in Toronto instead of Winnipeg. Some of you know why the delay occurred. Others can find me later and I’ll tell you the story over a beer.

For the past six years I’ve lived in Ottawa, on the unceded territory cared for by the Algonquin Anishnaabe people for hundreds of years, just as it has taken care of them.

I live on the Ottawa River, where no two days are alike. The river constantly changes, shaped by what is happening upstream, and how the downstream gets blocked or opened. Some days the river is swift-moving and of singular purpose. Others, change laps languidly, imperceptibly, at the shore.

It reminds me of the changes I am seeing in the care economy, where I have devoted a growing share of my time as the Atkinson Fellow on the Future of Workers. The pandemic spurred this evolution in my focus, and I’m so glad it did, because demographics will inevitably nudge a growing focus on the care economy’s role in economics, and someone needed to drive attention to that evolving reality in Canada.

The events of the last few years—pandemic, inflation, central bank rate hikes, increasingly polarized politics—have also made me think about our profession, and how change happens in economic thought and economic policies. Things seem constant—until they change.

Sometimes change creeps up on you. Sometimes it hits like a tsunami.

Sometimes system shocks—war, or climate change, or political upheaval, or just bad planning—urge change to happen. Sometimes people do.

What kind of people? Our focus often gravitates to the giants.

The namesake of the Galbraith Prize, John Kenneth Galbraith, qualifies. He stood six foot nine inches tall. In the 97 years he strode this earth, he cast a long shadow on our profession and changed the meaning of what it meant to be an economist. A popular economist. That is, an economist that non-economists could understand.

But Galbraith was not just popular. He was an economist who made a difference in the lives of almost everyone. An economist who changed how economists use our skills, and for whom. The story of Galbraith is a story of evolution, of economic thought and economic policies, of economic relevance. In the next few minutes, I hope to remind you that it’s when someone challenges and recasts the definition of economic relevance, change happens. You could be that person.

Today I will tell the story of the evolution of economic thought, and the story of the evolution of the care economy. It’s a story littered with both light and dark giants, humanizing forces and destructive influences. The characters populating these dynamics change, and so do the arenas of action. Every Goliath has its David. For me, the dark giant I am battling is the ascendant power of private equity in the care economy.

Gigantic Shifts In Economic Thinking

Giants have been part of our storytelling as long as we’ve been telling stories. Sometimes they are portrayed as violent monsters, sometimes as intelligent and kind. Leaders, even. Often depicted in counterpoint to our own more modest stature, stories about giants can remind us of our sometimes-surprising strengths. They always reinforce that it matters how power is used, in whatever size and shape it appears.

But even giants stand on others’ shoulders, and before the Giant of Galbraith, there was Alfred Marshall.

Like Galbraith, Marshall was a social economist. Born in 1842, he waited almost half a century to become influential. What did it mean to be a social economist then?

The first Great Depression gripped the richest countries of the world from 1873 to 1893, spawning dozens of revolutions, and ultimately World War I. It was amidst this era of tumult and turmoil that Marshall literally wrote the book on economics.

Principles of Economics was published in 1890 and introduced the concepts of demand and supply, price elasticity, diminishing returns and marginal utility. Galbraith said the 800-page tome was the first book on economics he ever read.

Marshall was the father of neoclassical economics and introduced the foundational concepts of microeconomics, defining our field of study for the next half century or more. Before Marshall, no one used charts, or explained how demand intersected with supply. Before Marshall, economists didn’t think about fixed and variable costs, or decision-making over the short- and long-run.

Marshall reconciled the classical theories of value with modern theories of price, based on the actual costs and processes of producing things.

It was no marginal revolution, if you’ll excuse the pun. He embraced the Industrial Revolution’s newly ascendant engineering concepts of optimization and maximization and used mathematics as a tool to simplify ideas. But if math could not “illustrate the examples that are important in real life…burn the math”.1

What made Marshall a social economist was his mission to explain human behaviour.

If the practice of economics is like a poker game—who can play and bluff their way to winning the game of explaining the world to the world—then Galbraith saw Marshall and raised him one, implicitly at the beginning of the Second World War, and explicitly not long after.

Change Your Thinking, Change Your Practice

Aware of its power, Galbraith was deeply critical of the ways economic theory lagged economic realities. Economic thought shapes public policy and practice. Galbraith shaped both, for decades.

His forte was empirical work. Evidence-based. Of the moment. News you can use. That’s why millions of “regular” people paid attention.

Son of a farmer in Iona Station, Ontario, he was raised to be relevant, and based his work on what people needed to know. His roots on the farm and in agricultural economics shaped agricultural policy in the Roosevelt administration during the 1930s.

During the Second World War, he headed the Office of Price Administration, which imposed limited price controls during World War II. Wartime production saw nominal GDP soar by 75 percent in four years, but inflation only increased by 3.5 percent, a truly astonishing feat. When the controls were taken off, in June 1946, inflation soared to 28 percent.

(As an aside: Dr. Isabella Weber was in town last night, delivering the Ellen Meiksins Wood Lecture. Her reminder of the power of price controls was met with a firestorm of derision in 2021. By 2022, though, both Europe and the U.S. had introduced policies that adopted this approach. Watch for my profile of this incredible mind-changing economist in the Toronto Star next week! Fun fact: Weber learned her trade at none other than the Marshall Library of Economics at the University of Cambridge. Giants can teach giants how to giant! It was an honour to meet this young woman economist with a spine of steel, and I can tell you without doubt—watch this space. She’s incredible.)

After the war Galbraith started writing about the evolution of markets. You know, what was actually happening, not what textbooks told you should happen.

American Capitalism (1952) documented how the neoclassical model of perfect competition missed the big story: the rising power of big corporations. This, he noted, could only be held in check by the “countervailing power” of governments and labour unions.

The Affluent Society (1958) coined the now well-known term, “conventional wisdom,” referring to the “esteemed acceptability” of well-worn but irrelevant ideas that accompanied the ascendance of unthinking conservatism. A key takeaway was that private affluence does not abate public squalor. Indeed, private growth is often accompanied by public decline. File that lesson away for later.

In The New Industrial State (1967), Galbraith meticulously documented how corporate America was morphing into mega institutions that held sway over public policy and our lives. There are lessons to be learned today from that analysis regarding the rise of private equity, which I’ll get to in a moment.

Galbraith’s influence in the corridors of power may have peaked by the 1960s (already by January 1961, Paul Samuelson was the author of the report on the State of the American Economy to President-elect Kennedy) but his influence on the public imagination and discourse continued to rise.

His wildly successful PBS TV series, The Age of Uncertainty, launched in 1977, was based on the book of the same name.

By this time, Galbraith was arguably the most widely read, heard and seen economist in history. A central economic teaching was to clarify the respective roles of markets and governments, the twin engines of economic capacity that could either maximize growth or maximize utility, or what we might today call quality of life. The balance between governments and markets determines economic outcomes for individuals and societies.

Giants Come In All Sizes

It was not long before Galbraith’s analysis and purpose were challenged by another giant. A giant named Milton Friedman. Standing at an imposing five foot three, Friedman was a contemporary of Galbraith. In fact, during World War II he rowed in the same direction as Galbraith and Keynes, economically. He was hired by the Treasury Department to help introduce the system of federal payroll tax withholding that helped finance the war effort.

Maybe he never got over it. The rest of his life was an unending campaign to restrict the state’s role, increase rights and reduce responsibilities of individuals and corporations.

It is unclear who will cast the longer shadow over the 21st century, Galbraith or Friedman.

In 1970, Friedman published a free market manifesto in The New York Times magazine entitled, “The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits.”

Friedman followed Galbraith’s wildly successful 1977 TV series and book with his own clapback. Free To Choose was also launched as a TV series and book. They came out in 1980, around the same moment as Thatcher and Reagan.

The three went on to dominate economic thought and popular discourse for the remainder of the decade. In the battle for balance between government and markets, the tide had turned.

It has now been over 40 years since the economic nostrum of “more market, less government” took hold. Galbraith noted “Milton Friedman’s misfortune is that his economic policies have been tried.”

He went on to say: “We can safely abandon the doctrine of the eighties, namely that the rich were not working because they had too little money, the poor because they had too much.”

Trickle-down economics should indeed be abandoned. It hasn’t delivered on its own terms. Now an aging population, a global pandemic, climate chaos, and the escalating sabre-rattling of increasingly fractious geopolitics call for more, not less, government. Yet resistance is fierce. Old habits die hard.

Even Giants Need To Learn How To Think

As Marshall, Galbraith and most of you understand: the most relevant economics explains human behaviour, helping us identify macro patterns and trends that result from the accretion of millions, even billions, of micro decisions, and how the macro shapes the micro choice set.

Galbraith’s thinking evolved as he plunged into the realities of farmers’ decisions, governments’ decisions, military decisions, and corporate decisions. His empiricism challenged orthodoxy. That’s the right way to challenge ideas: the what-is, not the what-ought-to-be.

As we learned from the inaugural Galbraith Prize in Economics lecture in 2007, delivered a year after Galbraith’s death by his son, Jamie—himself a professor of economics at University of Texas, Austin—Galbraith wove an intellectual fabric from many different economic threads over the course of his life.

In the intervening years, we’ve heard from eight other Canadian economists whose lectures have brilliantly illustrated the remarkable spectrum which Galbraith’s thinking spanned and spawned, revealing the colours and texture of progressive economic thought.

Kari Polanyi Levitt showcased the role of data, leading to the financialization of economics and financial crises. Mel Watkins described free trade as a bad religion that interrupted genuine human development. John Loxley took us on a journey of continuity and change at the IMF. Mike McCracken reminded us of the centrality of the pursuit of full employment. Lars Osberg explored the limits of steadily increasing inequality. Marjorie Griffin Cohen reminded us of the “appalling” masculinity of economic analysis. Jim Stanford produced a program for building a better global world order. Mario Seccareccia called for a paradigm shift in “conventional wisdom.”

Today’s era of polycrises, with overlapping challenges facing individuals, communities, businesses and governments, provides no shortage of new empirical realities that make for meaty topics for economists, as this year’s Canadian Economics Association meetings amply illustrate. What challenge will you choose?

The Care Economy Is A Galbraithian Topic

The pandemic shifted my attention to the one thing we all need at different points in our lives, from cradle to grave: care. The human need for care is a constant. But the way we access care is changing rapidly, affecting almost everyone. And that, in turn, is affecting how the economy at large works.

I have become increasingly concerned by the ballooning size and influence of markets in the domain of care, and the growing role of investment capital, particularly the kind that we know so little about in Canada: private equity.

The care economy matters more than ever. It is evolving, and how it evolves matters to all of us.

Just as Galbraith used his historic moments—the war, the post-war wave of corporate consolidation, soaring poverty amidst expanding prosperity—to explain how economic systems work, and how they could work, this moment demands we, as economists, pay more attention to the care economy.

I hope the next few minutes of this lecture will convince you of this urgency.

The Care Economy Is The Foundation Of The Economy

Caring has long been seen as a woman’s issue. It took forever to get the care economy on the political agenda, because historically care has primarily fallen to women to provide care at home for those too young, too old or too sick to work. This was most often the case when one breadwinner could support a family, and that breadwinner was most often a man.

Caring only recently became viewed as an economic issue of consequence. That’s for two reasons: 1) More working-age people are turning to paid care supports because they have to work to survive. They are unavailable to provide unpaid care. 2) The system of care is in crisis. Almost everyone has witnessed how the undersupply of care underscores the degree to which it is a foundation for virtually every other aspect of human endeavour.

My focus is on the aspects of the care economy that are becoming profoundly dysfunctional: childcare, long-term care and healthcare.

Beyond its role in our individual lives is its relevance to the economy. That’s very odd, because it plays such an outsized role as an input to the economy. Citizens and governments go nuts when roads and bridges are washed out, or electricity grids collapse; but social infrastructure is as critical to daily functioning as physical infrastructure. Witness what happens when childcare centres, long-term care facilities, primary care clinics and hospitals can’t serve our needs.

You may be surprised by the facts. Most people are.

To describe its scale: combine Statistics Canada’s measures of the industry of health and social assistance with the industry of education. (The health and social assistance sector includes long-term care, childcare, hospitals, homecare and primary care.) Together these two sectors contribute to and ultimately define human development and the economic potential of individuals and whole societies. That definition of the care economy accounted for 13.4 per cent of GDP in 2023. Its closest rival is real estate, which clocked in at 13.2 per cent of GDP.

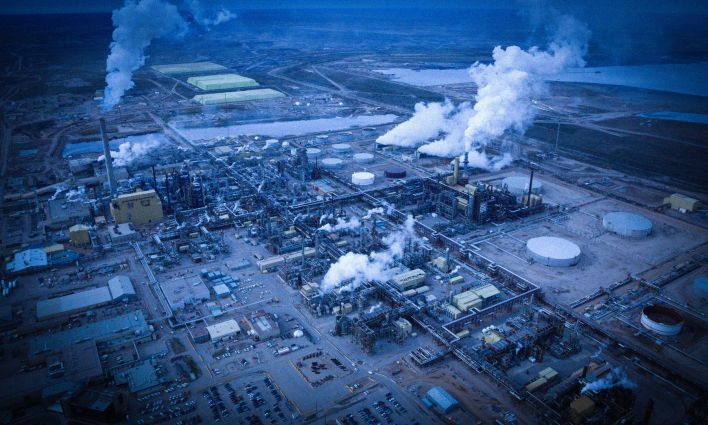

In 2023, the care economy was over a third bigger than all manufacturing (9.7 per cent); almost twice as big as construction or finance (7.5 per cent); and almost three times as large as the mining and quarrying sector (5.1 per cent), which goes well beyond oil and gas.

You’d never know it from the way the business press and decision-makers talk. Economic growth and productivity are rooted in exports, innovation, and investments in machinery and equipment in this view of the world. So much thought goes into the production of cars, oil and new homes; yet the care economy, already a dominant source of growth and innovation that could transform the economy and lives, faces chronic disregard and underinvestment.

Nonetheless, demographics and the increasing privatization and profitization of care have expanded the footprint of formal, monetized care in the economy over the last 20 years; and it's still growing. Indeed, the care economy may become the biggest single driver of future economic growth in the slow growth environment that is gripping every nation that had a baby boom after the Second World War and falling birth rates since.

I’m going to say that again: the care economy may become our biggest driver of future economic growth. Wow, right?

The Care Economy Could Create The Middle Class of the 21st Century

And here’s another “I bet you didn’t know”: the care economy already provides over one out of five jobs in the economy (21 per cent), eclipsing all other industrial sectors of the economy as a source of income for Canadian workers.

The care economy has the potential to become the backbone of the Canadian middle class, just as manufacturing was in the 1950s and 1960s. As it was in manufacturing at that time, the goal is to make every job a good job. Or at least more of them.

We treat the care economy as a derivative part of the economy, a nice-to-have once we’ve dealt with the “real” public policy priority, economic growth. But economic growth can’t be sustained without the care economy. Delivered with or without love, care is the foundation of economic growth.

Economists debate whether the richest nations in the world are entering an era of slow growth. I mentioned three drags on growth earlier: population aging, climate change and increasingly fractious geopolitics. Investors are finding it harder to make money from endogenous, organic growth, not only domestically but at the global level. A lot of money was made during the pandemic, and a whole lot more when the global economy reopened after the pandemic, Russia invaded Ukraine, and a wave of inflation not seen in 40 years was unleashed on the world. But that spike in profitability had two features: it was temporary, and a lot of that money migrated from the usual types of investment—publicly traded stocks and bonds—to private equity.

Private equity is a form of capitalism that is hard to monitor. That spells trouble for us all.

Private Equity Is Becoming A Gigantic Problem

You may recall Canada’s federal finance minister saying in the fall of 2022 that she was being fiscally responsible by “keeping our powder dry” to explain why she wasn’t increasing federal spending to support those struggling with inflation-induced affordability issues. She wanted to reserve funds to deploy if the economy fell into recession.

There’s another, far more explosive form of “dry powder” and it’s not being held in reserve to help you. It’s the term used in private equity markets to refer to cash ready and available to be put to work to make money for its owners, not you.

How much dry powder is available in the world of private equity is a question mark because—by definition and by law—it’s private. We only know what these investors want to tell us. Estimates from Prequin put the amount of dry powder available in early 2024 at $4 trillion USD globally. And that money is increasingly eyeing the care economy.

Just a few weeks ago, a huge conference in Washington DC brought together thousands of investors to talk about the potential for dealmaking in the homecare and long-term care businesses. In early March, Lina Khan, chairperson of the U.S. Federal Trade Commission, put the investment world on notice that, given the acceleration of private equity deals in anesthesiology, which consolidated market power and drove up prices across the entire acute care system, more interventions and possibly new regulation may have to occur to prevent that contagion from spreading. Meanwhile, the U.S. Senate is studying how private equity has advanced to own a quarter of all U.S. hospitals, changing costs and access in the process. California just tabled a bill that aims to lock private equity out of health care.

Here in Canada, we are walking towards a world of pain with our eyes wide shut.

We need to pay much closer attention to trends in private equity in the U.S., U.K., New Zealand, Australia, Europe, the Nordic nations, and in South Asia. The same patterns are playing out around the world. They reveal two truths, learned at high cost in the past few years.

Truth 1: Care workers go to work so that you can go to work. If there aren’t enough care workers to do the care that is needed, other workers will be unable to work to their potential. They will need to provide some amount of unpaid care. That will undercut the latent economic potential of a nation. If you’re worried about flagging productivity, at least prevent it from getting worse. And it will get worse if you don’t pay attention to the care economy.

Not to fetishize paid work, but we are in a new moment. Soon, one in four Canadians will be seniors, the biggest cohort of elderly in history. The dependency ratio will be the highest it has been in 60 years, when the boomers were born. It will continue not for a few years, as it did in the 1950s and early 1960s, but for decades; and this reality will unfold against a background rate of economic growth not of five or six per cent, as was the case more than half a century ago, but with growth hovering around two per cent or less. It won’t take much to push the system into long-term recession if we don’t get this right.

This is happening around the world as well: rapidly growing demand for paid care services, rapidly growing government financing; and a light touch on the rules, to facilitate a rapid expansion of supply. The care economy is turning into an economic wild west.

Truth 2: These are the perfect conditions for attracting private sector investors. But not just any kind of investment. Not publicly traded companies, by and large, who are regulated by security commissions, but private equity, for whom there are fewer legal requirements and fewer legal restrictions. They work within the rules (or lobby to change the rules) to shield themselves from scrutiny, responsibilities and liabilities through complex corporate structures.

As I have learned from my own recent look into private equity investment in the long-term care and childcare sectors, we now need forensic accountants to help us follow the money. Taxpayers’ money. Our money. And there’s a lot more money to come. The business of childcare alone is expected to double globally by 2030 (less than a decade!) to almost half a trillion dollars. But governments aren’t tracking what’s happening here. Neither are academics. Or journalists. Or think tanks.

Governments and economists may be moving slowly, but these private equity giants are flying high and moving fast. A private equity asset is held on average for four to seven years before it is sold.

The care economy is an appealing target because, in the era of slow growth, it is a sure source of organic growth, and provides a guaranteed, government-backed stream of regular revenue.

Billions of taxpayer dollars are being unleashed in Canada, the UK, the U.S. and the Anglosphere in general as societies struggle to address the twin pressures facing the smallest cohort of working age people in 60 years: high costs of care colliding with a high need for workers. Improved affordability and access, not profit, are the goals. But when billions of dollars suddenly appear, so do the profiteers.

Further, virtually every aspect of the care economy is ripe for the private equity playbook, with high potential to squeeze profits by lowering costs, hiking prices, and lobbying governments for new rules regarding staffing levels and qualifications, as well as fee rates.

Economists have long debated the pros and cons of privatization. This isn’t your daddy’s privatization, and these aren’t your typical corporate giants. Small-cap private equity creates the chains, which are bought by big-cap private equity firms. The game is ever-accelerating corporate concentration, and a quickening pace of bankruptcies. Private equity is creating momentum for plunder capitalism everywhere. It’s coming for the care economy.

Private Equity Isn’t New. It’s New In The Care Economy.

Though private equity comes in different sizes—family offices, institutional players like pension funds and banks, and other alternative investors, small cap, big cap—only deep pockets can come to the table. It’s a big stakes game. The lowest ante I’ve seen is $100,000. That’s what Wealthsimple says you need to have to even think about playing. But Wealthsimple is a bit player, taking a gamble to bring private equity ‘to the people’. The entrance fee to this world is usually in the multi-millions.

Private equity is a ruthless, even monstrous giant, because it’s always a big-foot strategy. Few of these investments produce more care, that is, add capacity. They are mostly “roll-ups,” purchases of existing operations with known capacity, revenue flows and profit margins. The “bigger is better” strategy of adding companies to one owner produces economies of scale in back-office functions, supply chains for bulk purchasing, standardized procedures to minimize costs and maximize revenues, and extra-billing for anything but the most basic service.

That’s all key, but the biggest payout comes from extracting higher rents (a sad irony for the many operators that sell their business with real-estate assets) and saddling the acquired companies with the debt payments used to buy them in the first place.

The pattern repeats with each sale: mergers and acquisitions grow market share, lower costs come from economies of scale and cheaper payroll costs, higher revenues come from using growing market share and/or captive markets (with little or no options) to set prices. However, the recipe for success has its limits.

The End Of The Road

What happens when you can’t juice more profit out of the enterprise? It goes bankrupt.

The Body Shop and Red Lobster are just two recent examples of successful brands unable to survive the rapacious appetites of takeover by private equity. This storyline has been repeated for decades and is now mushrooming across new sectors of the economy, including the care economy.

When it comes to the business of care, the extraction of profits always reduces the potential amount of care people receive, primarily but not exclusively through cutting labour costs by lowering staffing levels, reducing qualifications, eliminating benefits and pensions. As Canadian sociologists Hugh and Pat Armstrong have said for decades, “the conditions of work are the conditions of care.”

Just this week CBS aired a two-part series on how the arrival of private equity in the U.S. long-term care sector is leaving the elderly with substandard care and a shrinking set of choices as more facilities go bankrupt. In my Toronto Star column, I did the same analysis in Canada by examining how this model of acquisition is stripping real estate values from our long-term care homes, jeopardizing care by reducing staffing or simply closing the operation to build condos. Wait lists for care are soaring, with consequences spilling back upstream across the whole system. We taxpayers are left paying for this mess.

The Norwegians call it the tapeworm economy, parasitic investments that grow in size as they absorb nutrition from public funds, weaken care and degrade jobs.

In Canada, at best we’re sleepwalking through it; at worst, actually, we’re rewarding companies that are providing allegedly criminal levels of long-term care, as I documented in another recent Star column.

The New Giant In The Story Of Capitalism: Private Equity

Not just big in scale, these big-foot owners are proliferating in number across the economy. They are the new giants of capitalism—and now care. The same patterns are unfolding across long-term care, hospitals and home care, and child care in nation after nation: public and non-profit operators are struggling to keep things running while private investors reap growing profits. All fuelled by the public dime.

In Canada, we’re not learning fast enough from others’ experiences to meaningfully apply the brakes. The U.K., the U.S., and Australia have all seen private equity investment rip and strip its way through multiple sectors of the economy for two decades or more.

Sadly, there are many, many, many international examples of how overleveraged owners drove successful operations into the ditch, but in the care economy, the consequences are starkly different than from retail or restaurants or journalism.

Paid care is already chronically undersupplied. What happens when the enterprise that goes bankrupt serviced the care needs of 10 or 20 per cent of a community? Who will take care of preschoolers, the majority of whose families require all available adults to work? In long-term care, more elderly are being evicted from their nursing homes so owners can cash in on the real estate bonanza, but there’s no other capacity to turn to. Where will people without supports or bags of money live out their lives? And what will it mean to productivity and GDP per capita when the smallest working-age cohort in more than half a century can’t get their own healthcare needs met?

The dynamic now at play in the care economy has terrible human consequences. It has devastating economic consequences too, on workers who provide care and workers who need paid care to be provided. When the inevitable happens —accelerating numbers of companies providing care bought and sold by private equity, driving more of them to collapse—the disruption faced by individuals and the economy at large will be fearsome.

The care economy is too important—economically and at a deeply personal level—to surrender it to market forces.

Galbraith knew this. He worried about “our tendency to overinvest in things and underinvest in people.”

That’s my worry too. We need guardrails on our public investments to make sure our money is being used to finance our long-term needs/interests—caring for each other—and not some investor’s short-term gain.

We can wait for these predictable disasters. Or we can pay attention to how the story is unfolding in other nations and learn from their defensive strategies.

This isn’t a murder mystery. We can write the next chapter of this story.

What Is To Be Done

One of my favourite Galbraith quotes is this: "In all life one should comfort the afflicted, but verily, also, one should afflict the comfortable, and especially when they are comfortably, contentedly, even happily wrong."

Today, the comfortably contented are afflicting the afflicted. It’s a situation light on poetry and hard on the soul.

But, as Galbraith said about Marshall, "you had to know what was wrong before you could know what was right.” Empirical evidence and good theory help prevent oversteering, in any direction. We don’t have either at the moment.

We need all orders of government to monitor these investments and provide transparent reports to the public.

For that to happen we need to change laws to require more disclosure. For a start, if a corporation receives public funding to provide care, it should have to disclose:

- the number and size of care facilities controlled by that owner;

- how that ownership fits into more complex corporate structures, including shells and interlocking directorships;

- its financial-backing (Public? Non-profit? Publicly traded? Private equity?); and

- turnover, of both ownership and staffing.

We also need to place limits on market shares. Perhaps a threshold on the number and scale of operations held by a single owner. Perhaps market share in a given geographic catchment area. Few categories of consumption are more inelastic than the demand for paid care. What does that mean? We’ll pay whatever we have to pay, or do without.

Given how debt charges are a leading cause of bankruptcies in acquired facilities, there should be limits on the amount of debt used to purchase care operations. Would-be homeowners need to put down 20 per cent of the purchase price of a home, or purchase mortgage default insurance and pay higher borrowing fees. We should enact similar rules when it comes to the purchase of care facilities.

That giant sucking sound you hear is the withdrawal of dividends and fees from the revenues of acquired companies, irrespective of what that means to the provision of care. In some cases this has bankrupted operations within months of new ownership. In the U.S. there have been federal bills tabled, barring the extraction of dividends (and further outsourcing, often to other companies owned by the shell organization) for two years after purchase.

Finally, we need to come up with a system-wide plan—across childcare, healthcare, and long-term care—that ensures we have the right person to do the right job at the right time, and that we train, attract and retain the right number of people, along with the right labour-enhancing technologies.

What This Means For Economists Today

Marshall intersected demand with supply. Galbraith intersected the roles of markets and governments. We need to intersect capital and labour in the care economy, and treat both as potentially transformative.

Galbraith showed us how real-time information should evolve our critiques and economic thoughts, and emphasized that thinking can’t be the only end result. A better world needs action, too. It is certainly true that there is plenty of action on the other side of the ledger among the dark giants of private equity, so we need to level up—on behalf of society’s most vulnerable, as well as, let’s face it, our future elderly selves.

As economists, we need to follow the money and reveal the micro and the macro of this transformative moment. There are plenty of ways to challenge the orthodoxy about the balance between governments and markets, plenty of ways to alter the river’s flow, to bend its course.

And don’t worry if you’re a shorty, like me. You don’t need to be a giant. You just have to be willing to stand up to them.