“Study after study describes poverty as a profound and damning thing for child development. The political response has been to watch poverty levels dip and rise. On the sidelines, statisticians have debated how measurement might best occur...too often with a view to reporting the lowest numbers possible. There have been champions. Despite that Canada has arrived at a shameful place.

Right now our inaction tells the world this nation thinks one in four children are not worth it.

Not worth feeding.

Not worth shelter.

We've been persuaded to take some comfort in how resilient some children can be. But here's the bottom line...Our lack of investment in child poverty reduction has destroyed or diminished an untold number of young lives over this 25-year period.” This was the response of Pauline Raven and JoAnna Latulippe-Rochon to the state of child poverty in the province 25 years after the resolution to end child poverty by the year 2000 was passed unanimously in the Canadian House of Commons. Pauline and JoAnna wrote the first report card in 1999.

The record: 1989 to 2012

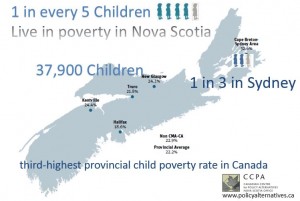

According to the 2014 Report Card authored by Lesley Frank, a higher percentage of Nova Scotia children are living in poverty now than was the case in 1989. The percentage of children living in poverty in 2012 (most recent data available) in Nova Scotia is 22.7% higher than it was in 1989. There are 37,900 children or more than 1 in 5. This is the third-highest provincial child poverty rate (after Manitoba and Saskatchewan), and the highest rate in Atlantic Canada. Cape Breton has one of the highest rates in Canada: 1 in 3 children (32.6%) are living below the After-Tax (LIM). Rates in Kentville (24.4%) and New Glasgow (24.3%) were also above the provincial average—approximately 1 in 4 children in these areas live in poverty. Truro reported a rate of 21.8%, and Halifax 18.6%. The poverty rate for rural Nova Scotia is 22.9%.

Which children and families are most vulnerable to poverty?

The short answer is we don’t know: the data doesn’t tell us in terms of those groups whom we know are more vulnerable to living in poverty (racialized groups, new immigrants, First Nations, people with disabilities, women).

Here is what it does tell us:

<li>lone-parent families experience a much greater likelihood of living in poverty than children living in families headed by couples: In 2012, <strong>half</strong> (49.9%) of the children living in lone-parent families in Nova Scotia lived below the AT-LIM (24,600 children).</li>

<li>children in larger families are more likely to live in poverty: The rate for children in families with three or more children was 28.6% in 2012: that’s 20.7 % more than the rate for families with only one child, and 69.2% more than families with two children.</li>

<li>children in families that depend on income assistance are particularly vulnerable to poverty; all of these families face a significant gap between their welfare income (income assistance payments, federal and provincial child tax credits, and goods and service tax credit payments) and the poverty line.</li>

Impact of Child Poverty:

Inadequate incomes, income inequality, and insecurity in relation to the essentials of life —food, housing, clothing, and heat—to say nothing of lack of access to child development, childcare, or recreation programs--are major barriers to the healthy development of children. Evidence suggests that children living in low-income households typically suffer from multiple disadvantages throughout their lives, including poorer educational outcomes, poorer health, poor dietary intake and nutritional status, and higher rates of delinquency. The UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre reports that 30% of children in poor families in Canada are developmentally vulnerable compared to 15% of children in higher income families.

Why did Child Poverty increase in Nova Scotia?

The piecemeal increases in social assistance spending and marginal tax adjustments that recent governments claimed would alleviate the burden of child poverty were inadequate measures. Such policies have not been robust enough to address insufficient welfare incomes (thousands of dollars below poverty thresholds). The limited commitment to family policy to support parents in the workforce, rising housing and food prices, increases in low-waged precarious employment, inadequate support for rural transportation, literacy, adult education and skills development programs, still stand in the way of child poverty eradication.

How do we end child poverty?

Ending family and child poverty is achievable and depends to a large degree on governments’ agendas for poverty reduction and eradication, as well as their broader social and economic public policy priorities (including tackling income inequality not giving tax breaks to those who least need it as previously argued). Government transfer payments do reduce the rate of child and family poverty, but more needs to be done.

Specifically, we need:

<li>An enhanced national child benefit for low-income families to a maximum of $5,600 per child (2013 dollars, and indexed to inflation)</li>

<li>Combined total welfare income (Nova Scotia income assistance payments and tax benefits) to be high enough to ensure that families can cover all their basic needs.</li>

<li>A minimum wage indexed to 70% of the median Nova Scotian wage, and stronger labour standards</li>

<li>Public investments aimed at poverty reduction for families, which must include access to a well-designed, affordable early learning and childcare system.</li>

Will our governments heed the evidence of the last twenty five years, re-commit themselves to ending child poverty, and most important of all, take concrete action to keep the promise this time?

Though an insufficient strategy by many accounts, the Nova Scotia Poverty Reduction Strategy did set the following benchmark: 16,000 children under 18 representing 8.7% of the population. Reaching this target would ensure that at least 20,000 children would no longer live in poverty in Nova Scotia. The rightful target should be the complete elimination of child poverty.

Let’s not let another generation suffer broken promises.

Christine Saulnier, Nova Scotia Director, CCPA.