Our content is fiercely open source and we never paywall our website. The support of our community makes this possible.

Make a donation of $35 or more and receive The Monitor magazine for one full year and a donation receipt for the full amount of your gift.

One hundred years ago—July 1, 1923—the Canadian government passed “An Act Respecting Chinese Immigration.” Known as the Chinese Exclusion Act, it was an overtly racist law prohibiting the arrival of newcomers from China. It also required all people of Chinese heritage, including the Canadian-born, to register with the federal government in order to stay in the country. Chinese Canadian communities across the country mobilized to lobby against the act but in the end their efforts failed to stop its passage. Thus, July 1 came to be known as “Humiliation Day” for many Chinese Canadians.

On the 100-year anniversary of the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act, The Monitor is releasing a series analysing the context in which the Act passed, resistance to the law, and its historical legacy. These articles are a serialization of the booklet 1923: Challenging Racism Past & Present, which you can read in full at https://challengingracism.ca/

}},212234:{type:breakoutBox,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{boxPosition:right,boxColour:null,breakoutCopy:

Read the full series

n

This article is one piece of a larger series, which looks at the history of the Chinese Exclusion Act, 100 years after it passed in 1923. We will update this list with hyperlinks as the series is released.

n

Chapter 1: Challenging Racism, 1912-1914

n

Chapter 2: Anti-Racism and the War, 1914 – 1916

n

You are here: Chapter 3: The Revolts, 1917-1919

Chapter 4: Global Challenges to Racism, 1919-1922

Chapter 5: Backlash, 1920-1922

Chapter 6: The Chinese Exclusion Act and More, 1923

Echoes of 1923?

}},212235:{type:copy,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{copy:

The onset of war in 1914 eventually impacted the economy, increasing the demand for workers in many industries. Faced with racist barriers preventing them from joining the military, racialized workers provided essential labour in key industries, particularly on the west coast.

They also demonstrated a growing determination to create or join unions to assert their rights in the workplace, where they had lower wages and poorer working conditions than white workers. The unions described below represent a seldom-recognized era in the history of the Canadian labour movement marked by anti-racist and radical labour politics that forged rare cross-racial class solidarities.

South Asian immigrant Husain Rahim was the first racialized person to hold elected leadership in the Socialist Party of Canada. Working on the party’s newspaper, The Western Clarion, Rahim collaborated with white socialists such as Henry M. Fitzgerald, Joe Naylor, J. Edward Bird, and William Pritchard. These militant and anti-racist trends erupted in a labour revolt toward the end of the war, culminating in the formation of the One Big Union and the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919.

Local 526, Industrial Workers of the World

Formed in 1906, this union was comprised mainly of Sḵwx̱wú7mesh (Squamish) and səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) longshoremen working the Vancouver waterfront alongside other racialized workers. Meetings were held on səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh) territory. Though the union disappeared soon after, the workers remained toiling on the waterfront during the war. The union would later reform in 1924 as the Lumber Handlers’ Association, led by Andy Paull, a chief of the Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Nation.

Longshoremen, many of them Indigenous, at the Moodyville Sawmill in Vancouver, 1889. Some, William Nahanee (centre, with laundry bag) later founded the Bows and Arrows IWW local. Photo: City of Van Archives Mi P2

Coalminers Strike (1912-1914)

This bitter conflict saw the coalminers on Vancouver Island defeated. Asian Canadian workers who crossed the picket lines to work were often blamed for this bitter outcome. But to socialist Joe Naylor, one of the leaders of the strike, it was 200 special police who forced them back to work: “They would not have gone to work until the white men had gone if they had been left to themselves, he told the BC Federation of Labour delegates in 1914. It was not Asian workers who were “the curse of BC, it is the white men, and especially the men who have come from the same country as myself, and that is England, that are the real curse in this province.

This was a turning point as radical unionists began to see racialized workers as allies in the fight against corporations. Naylor would go on to lead the movement for a united labour body in the One Big Union.

Asian Canadians in the Labour Force

Excluded from professions such as law or medicine, Asian Canadians became an important part of the labour force in the mills, mines, and fishing industries on the west coast. Labour shortages during the war saw Asian Canadians representing over 20 per cent of BC’s industrial labour force by 1919. This increased their economic leverage and Asian Canadian union activism accelerated along with other workers.

Group portrait of workers at Carlson mill, Nakusp, BC, 1912-13. Names include Jagat Singh, Lashman Singh, Santa Singh, Serhan Singh. Arrow Lakes Historical Society, 2014.003.506

Fishing

Japanese Canadian fishers were extremely productive and able to obtain fishing licenses in key sectors of the industry. This created resentment on the part of some white and Indigenous fishers that racist politicians tried to amplify using divide-and-rule tactics. In the canneries, Indigenous and Asian Canadians, including large numbers of women, worked together often in isolated stations along the coast.

Mining

Workers of Chinese and Japanese heritage were an important part of the labour force in the mines of British Columbia. Stigmatized by racism, they were often relied upon to take on difficult and hazardous jobs. The mortality statistics from the Cumberland Museum reveal the disproportionately higher toll that Asian Canadian miners paid in explosions in the Dunsmuir mines:

1901 No. 6 Mine: 64 dead

(35 Chinese, 9 Japanese, 20 White)

1903 No. 6 Mine: 15 dead (all Chinese)

1922 No. 4 Mine: 18 dead

(9 Chinese, 6 Japanese, 3 White)

1923 No. 4 Mine: 35 dead (19 Chinese, 14 White)

Forest Industry

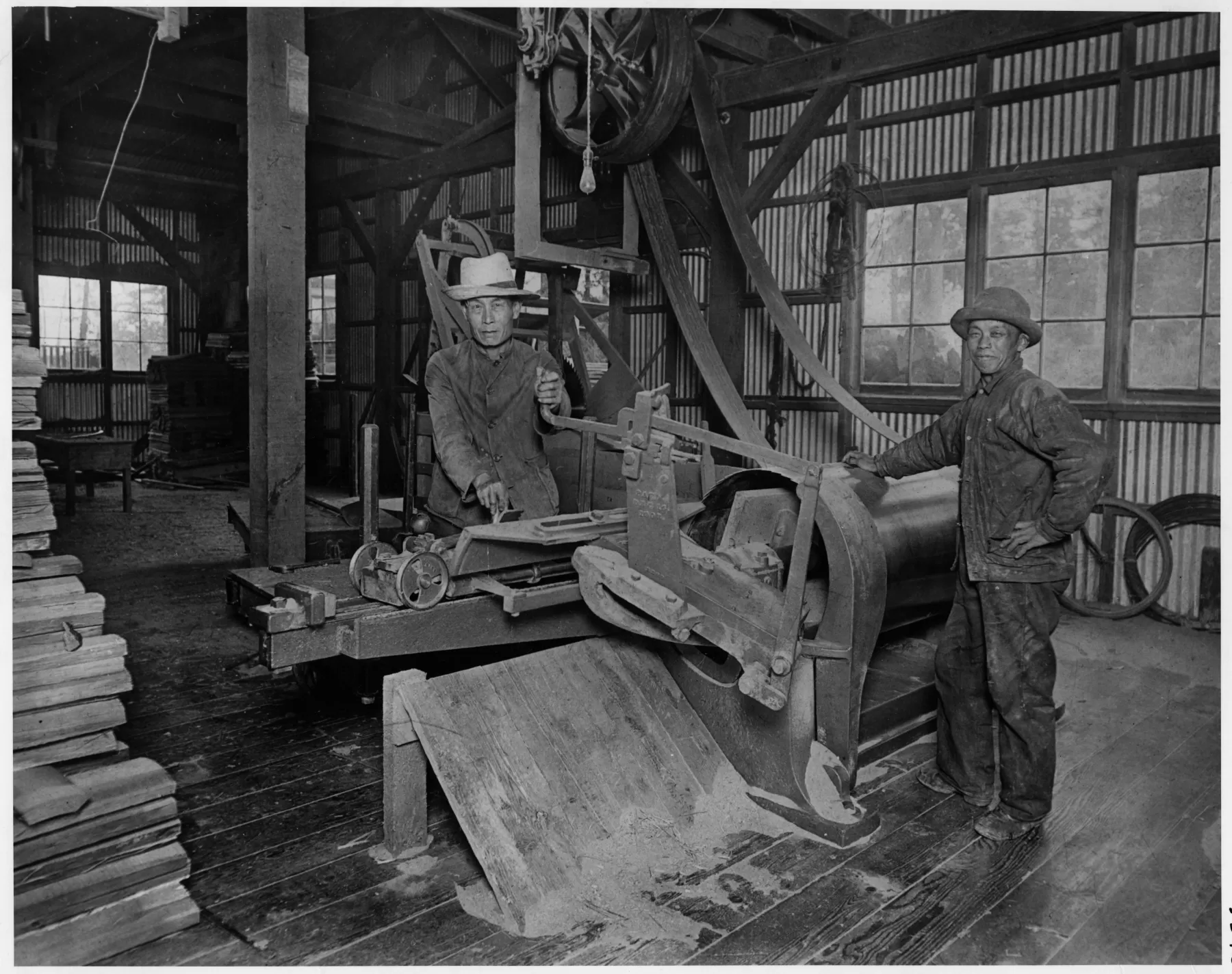

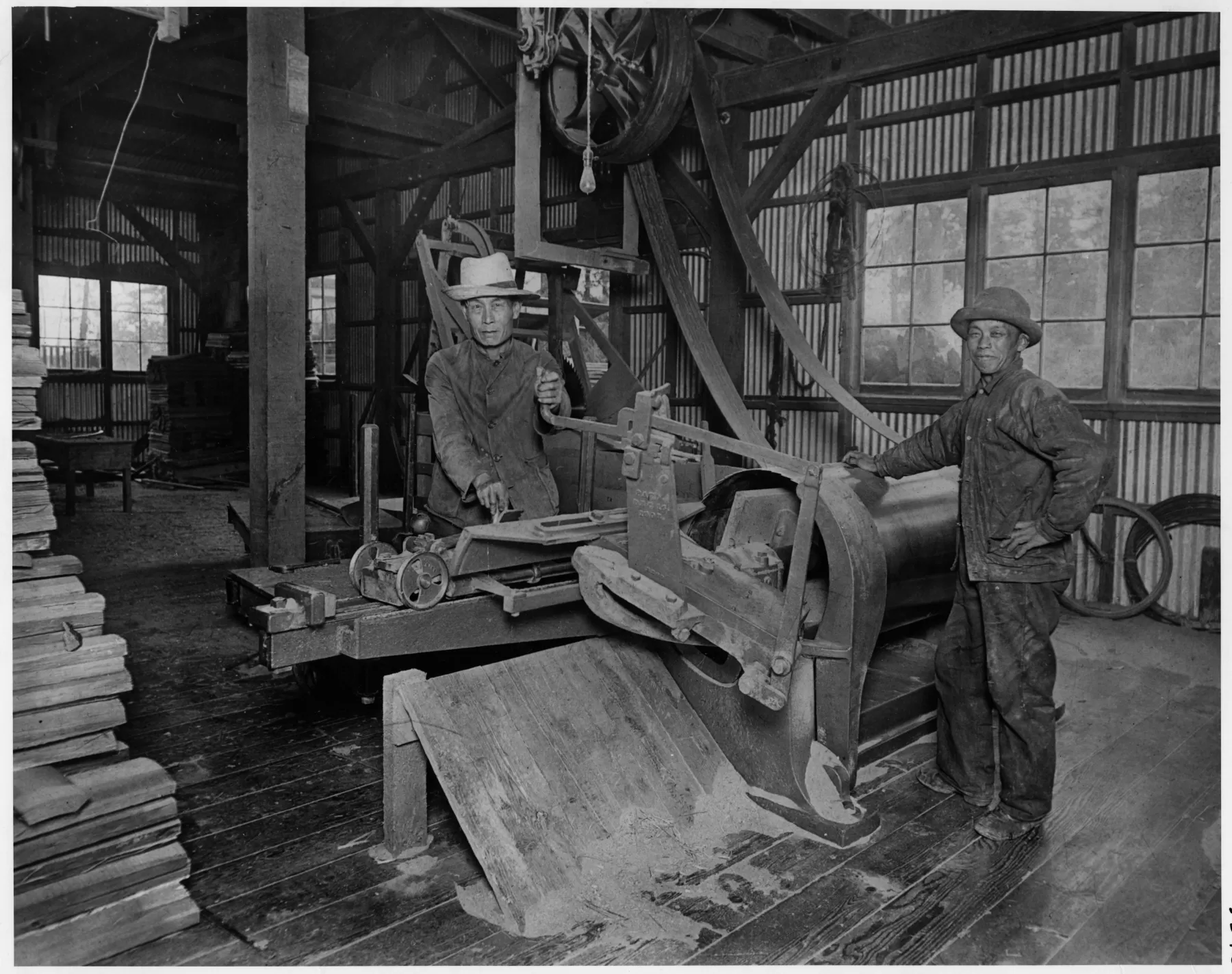

In the saw and shingle mills alone, approximately 3,500 workers were of Chinese, Japanese or South Asian heritage. As production pressures increased so did strike activity.

Excluded from various professions, workers of Chinese heritage had come together in the Chinese Labour Union (Zhonghua Gongdang) in 1916 to advocate for Chinese workers, who received unequal treatment relative to white workers in the same occupations.5 The union would also promote the formation of the Hawkers Association and the Chinese Shingle Workers Union.

Beginning in 1917, a strike wave began that helped catalyze the 1919 general strike in Winnipeg, which was supported by general strikes in many other cities across Canada, including Vancouver and Victoria. Initially, such strikes were local affairs. For example, in July 1917, hundreds of mill workers producing shingles organized by the Chinese Shingle Workers’ Union went on strike for the eight-hour day. Activists reached out to the Chinese workers with Chinese-language leaflets urging the eight-hour day.

At the time, The BC Federationist reported that the Shingle Workers’ Union officials felt that if they could be “as sure of some of the married white workers as they are of the Chinese, there would be no difficulty in enforcing union conditions throughout the jurisdiction… But at that, it’s a sight for the gods.” The employer threatened to replace the Chinese workers with white women, the only other labour source available at the time, given the war.

Men working with a barrel machine at Sweeney Cooperage Ltd. Photo: Vancouver Public Library 3542.

Although unsuccessful in gaining the eight-hour day, the strike expressed a new and growing cross-racial class solidarity. A year later, in August 1918, a group of workers in Masset engaged in a job action over wages. According to press reports, seventy Chinese and Indigenous workers “tied up the plant.”10

The Chinese Shingle Workers Union, affiliated with the Chinese Labour Association, took strike action against coastal mills again in March 1919.11 The mill employers attempted to cut wages by ten percent, provoking a walkout involving hundreds of workers, mainly of Chinese heritage. The chief negotiators were Fung Sing Guong (馮勝光) and Lui Gan (雷根).12 Unions like these would go on to support labour actions during the general strike wave of 1919.

The Sleeping Car Porters Union

In April 1917, John Arthur Robinson, J.W. Barber, B.F. Jones, and P. White led the formation of the Order of Sleeping Car Porters (OSCP), one of the first Black labour unions in North America. At the time, almost 90 percent of Black men in Canada worked in connection with the railways in underpaid jobs with terrible working conditions. However, the Canadian Brotherhood of Railroad Employees (CBRE) would not allow Black people to become members.

By 1919, the OSCP won a first contract with Canadian National Railways (CNR) with improved wages and job protections for all porters. Canadian Pacific Railways, on the other hand, was even more resistant to unionization than the CNR, forcing employees to sign contracts that prohibited union activity and firing employees involved in organizing.

Black Porters employed by the Canadian Pacific Railways, 1920s. Photo: Provincial Archives of Alberta, A9167.

Porters were largely well-educated university graduates, but segregation in the labour market and racism confined Black workers to low and unskilled job positions where they waited on white consumers and answered to white managers and bosses.

“Smartly dressed and smiling Black train porters were a familiar sight for white Canadian travellers and corporate executives. The sight of Black men catering to white people’s needs and desires fulfilled fantasies of white superiority, while structural racism ensured that porters came from a plentiful and expendable labour pool.

As porters criss-crossed the country in Canada and the US, they raised awareness of human rights issues and social and political problems facing their communities across North America, fostering a “powerful diasporic consciousness.” One of the newspapers they distributed was The Canadian Observer, known as “The Official Organ for the Coloured People in Canada.” It ran from 1914 to 1919.

The porters also established the Sleeping Car Porter’s Business Association, later named “Essceepee Limited,” which served as a credit union and provided investment opportunities for Black people. An important institution of Black activism, the Canadian Government recognized the union as a National Historic Event in 1994.

The 1919 General Strikes

William Pritchard, the editor of the Western Clarion from 1914 to 1917 and a leader of the Socialist Party of Canada, worked fervently with other socialists such as Joe Naylor to bring workers together. Their work resulted in the 1919 convention of the BC Federation of Labour, which declared: “This body recognizes no alien but the capitalist” and “Asian workers should be encouraged [to join] white unions for it is a class problem, and not a race problem that confronts the white millworker in BC.”

After taking the BC Federation of Labour convention to Calgary, the labour militants went on to form the One Big Union. This movement had strong support from unions, such as the newly formed and multi-racial Lumber Workers Industrial Union. Out of a membership of 5,000, the Lumber Workers Industrial Union reported that only 34 voted against the OBU.

}},212244:{type:copy,enabled:true,collapsed:false,fields:{copy:

The labour revolt came to a head in 1919 with the general strike in Winnipeg, which spawned sympathy strikes all over the country. These strikes represented an upsurge of worker militancy backing demands for union recognition and decent working conditions. In Winnipeg, 35,000 workers in both the private and public sectors went on strike, shutting down the city. Municipal police, who wished to join the strikers, were fired.

Employers and public officials portrayed the strikers as revolutionaries who were led by foreign agitators, mobilizing conservative veterans, the mounted police, and local militia to violently suppress the strike. June 21, 1919 became known as ‘Bloody Saturday’ after mounted police and militia attacked strikers and their supporters, killing two and injuring dozens. Strike leaders were detained, including William Pritchard. He and six others were tried for ‘seditious conspiracy’ and sentenced to a year in prison.

The general strike also attracted the support of the Order of Sleeping Car Porters, who donated to the strike fund, participated in walkouts, and suffered job losses in retaliation for their involvement in the strike.

Indigenous Resurgence

Labour was not the only social movement on the rise in 1919. First Nations had begun to mobilize regionally and nationally and were taking note of the emerging power of organized labour. This created new challenges for white supremacy.

League of Indians of Canada

In 1919, a returned veteran, Frederick Ogilvie Loft (Six Nations) made extraordinary efforts to bring First Nations together in the pan-Canadian League of Indians of Canada. In a letter to Chief Murray in Oka, Quebec, he explained, “We as Indians, from one end of the Dominion to the other, are sadly strangers to each other,” emphasizing that the day had past when “one band or a few bands” could free themselves of “officialdom” or stop the eroding of their lands and rights.

Pointing out how political power rests on a foundation of organizing, he said, “Look at the force and power of all kinds of labour organizations, because of their unions.” Indigenous organizing was driven by a desire to win rights for returning veterans, as well as in response to the Ontario government’s attempt to sell First Nations lands through a bill called the Oliver Act.

Fred Loft with military medals at the former Ohsweken Orange Lodge at the Six nations Fair grounds. Photo: Six Nations Legacy Consortium Collection, Six Nations Public Library

The League faced intense opposition from the Department of Indian Affairs (DIA). One Indian agent wrote to Duncan Campbell Scott, the DIA’s assistant superintendent, regarding the League:

“I do not know if you are aware of the movement but I am suspicious of it, I don’t like the tone of it, it looks like the I.W.W. [Industrial Workers of the World] or O.B.U. [One Big Union] or Balshevic [sic]. I have advised my Indians to have nothing to do with it, at least not until it had your sanction.”

Scott replied, “You are quite right in advising your Indians to have nothing to do with it.”

Despite DIA opposition, the League of Indians initially gained substantial support, expanding rapidly to hold conventions attended by hundreds of delegates in Sault St. Marie in 1919, Manitoba in 1920, Saskatchewan in 1921, and Alberta in 1922.

The Allied Tribes of British Columbia

The first general meeting of the Allied Tribes took place at Spences Bridge in June 1919, where they adopted the now famous “Statement of the Allied Indian Tribes of British Columbia.” The meeting and statement happened in response to the BC government’s release of the McKenna-McBride Commission under the leadership of John Oliver. The commission recommended land increases for reserves alongside reductions that were worth three times that of the additions. Although the report had been completed in 1916, the Department of Indian Affairs had refused to release it, fearing intense opposition to its findings. Those fears were confirmed by the Allied Tribes statement, in which they firmly rejected the report and reiterated their demand for a legal ruling regarding their title to the traditional and unceded territories of BC.

In response, the federal government opted to force through the land theft, introducing Bill 13 in parliament in March of 1920. Despite forceful lobbying on the part of the Allied Tribes, the government pushed ahead, authorizing the government to implement the McKenna- McBride recommendations “without consideration of Indian title, land rights, or past promises and laws.”22 With this legislation in hand, the federal government made a last-ditch attempt to press First Nations to accept the report with minor modifications. Indigenous leaders Peter Kelly, Ambrose Reid, and Andrew Paull refused to concede, demanding the issue of land title be brought to the British court system.

The revolts of 1919 rocked Canada on multiple fronts, echoing a broader global insurgency against racism, imperialism, and colonialism that was taking place throughout the world.