Only Temporary?

Navigating job shifts in Canada’s colleges and universities

Labour Force Survey data suggests there has been a general shift in the kind of work on university and college campuses, from permanent to temporary. But what are the implications of this shift? Building on the provincial analysis in the CCPA’s February 2018 report No Temporary Solution, we looked at national numbers for 1998 to 2017 to try to better understand three issues:

- To what extent is this shift taking place, and are temporary workers across the sector experiencing it differently?

- Are there gendered implications to this shift?

- What are the impacts on university and college faculty (spoiler – a lot of free labour)?

First, some general numbers: In 1998 there were 244,300 employees across the entire sector, 85,900 of whom self-identified as academic staff. By 2017 those numbers had grown: of the now 382,300 workers employed in Canada’s universities and colleges, 124,700 were academic staff.

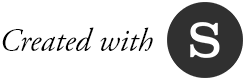

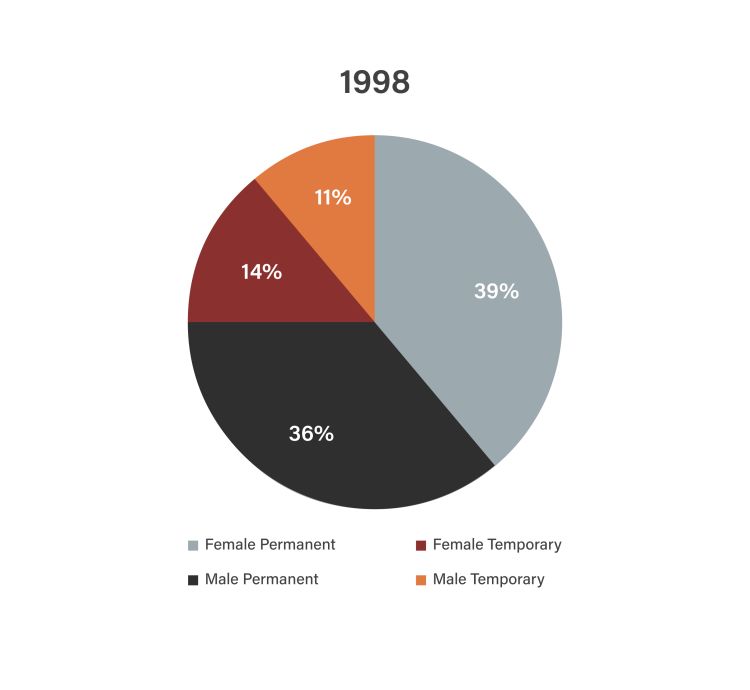

Temporary workers now make up 36% of the entire post-secondary workforce across Canada, up from 25% in 1998.

The charts below provide a more detailed breakdown, showing a general decline in the proportion of permanent full-time workers, a similar decline for permanent part-time, and an increase in both full-time and part-time temporary workers.

There have been other changes in the conditions of work. In 1998, 6.8% of all workers in the sector were multiple job holders (of those, 66% were permanent, 34% temporary). By 2017, 9.2% of all sector workers were multiple job holders, but the proportions had shifted more dramatically: 48% of multiple job holders were permanent and 52% were temporary.

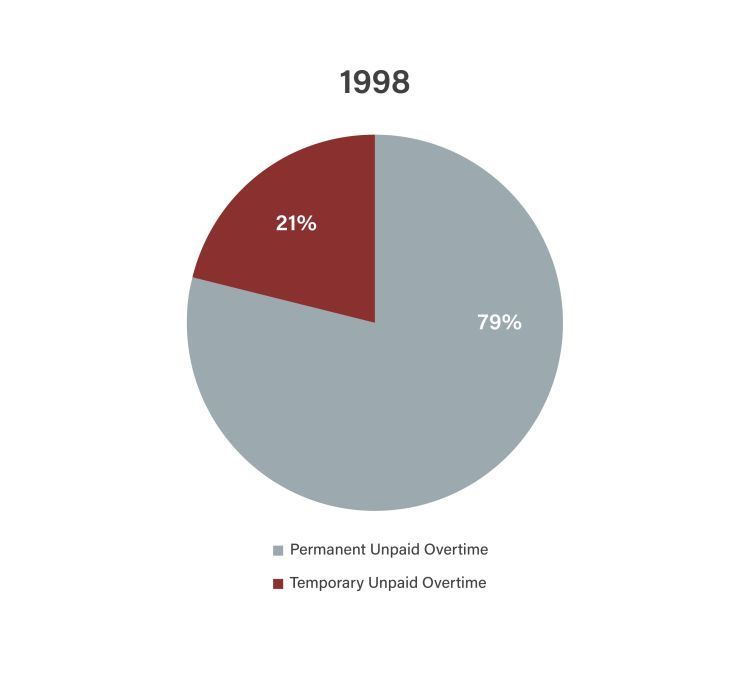

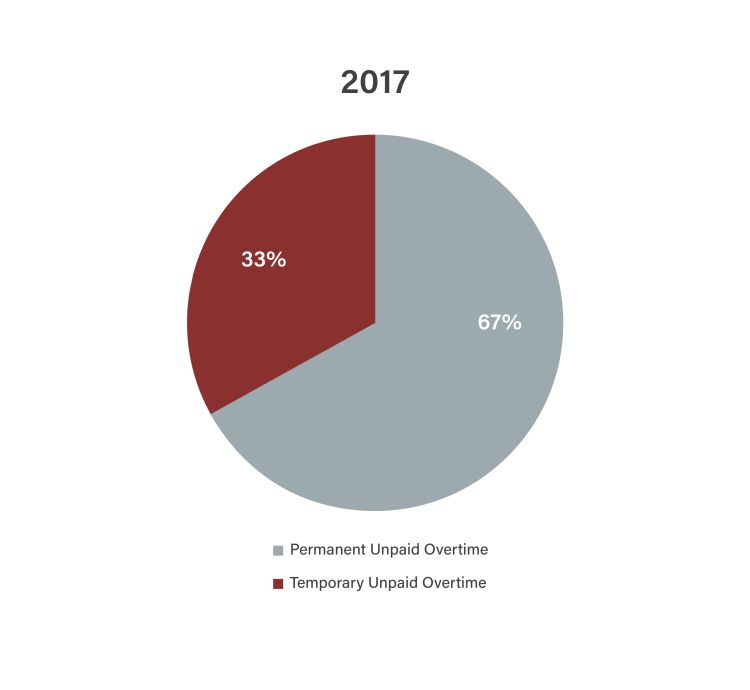

A growing percentage of temporary workers is also working for free. The proportion of workers in the sector working unpaid overtime remained unchanged from 1998-2017, at 18.5%. But out of those working unpaid overtime during this period, the proportion that was permanent declined from 82% to 68%, while the proportion that was temporary increased from 18% to 32%.

The share of involuntary part-time workers that are temporary is increasing as well. Between 1998 and 2017, the proportion of involuntary part-time workers in the whole sector increased only slightly from 4.5% to 4.8%. However, of those involuntary part-time workers, the proportion who were temporary rose from 56% to 73%.

The move from permanent to temporary also has gender implications. Women have, since the start of our data set, fairly consistently made up a greater proportion of the sector (52.6% in 1998 and 55.3% in 2017—though in 1999 they represented 48.9%). Since 1998 there is an increasing proportion of both men and women in temporary work, and a decreasing proportion in permanent. And as women make up a greater proportion of the sector, a greater proportion of women are also in temporary work (increasing from 13.5% to 19.6% of the sector since 1998, with a high of 20% in 2014).

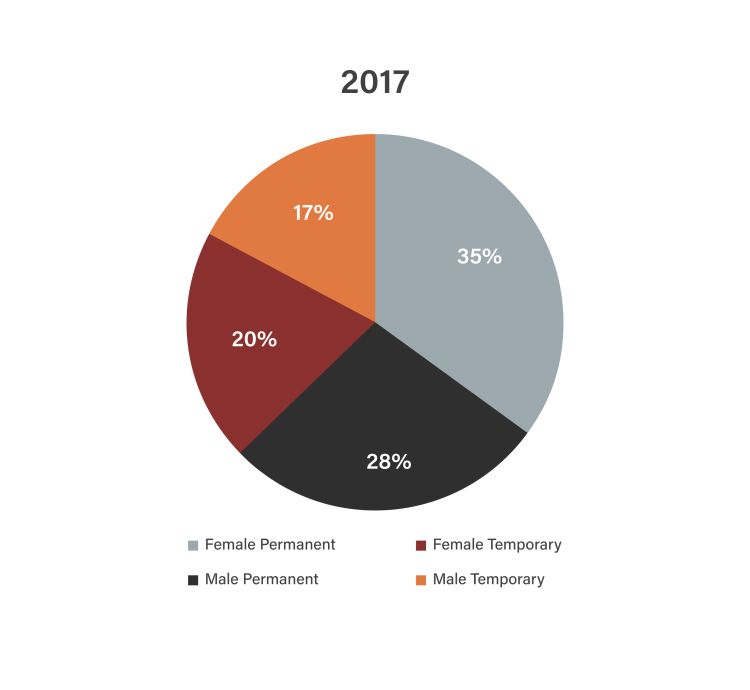

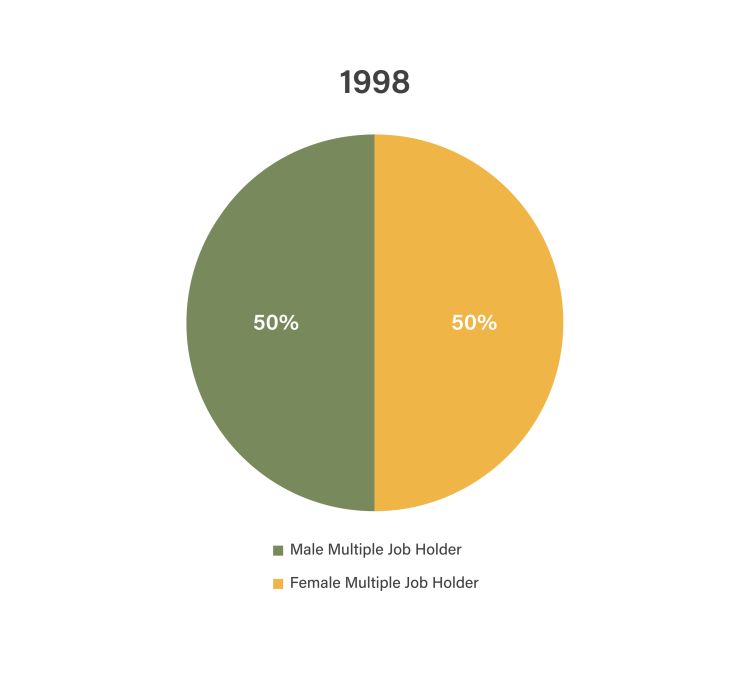

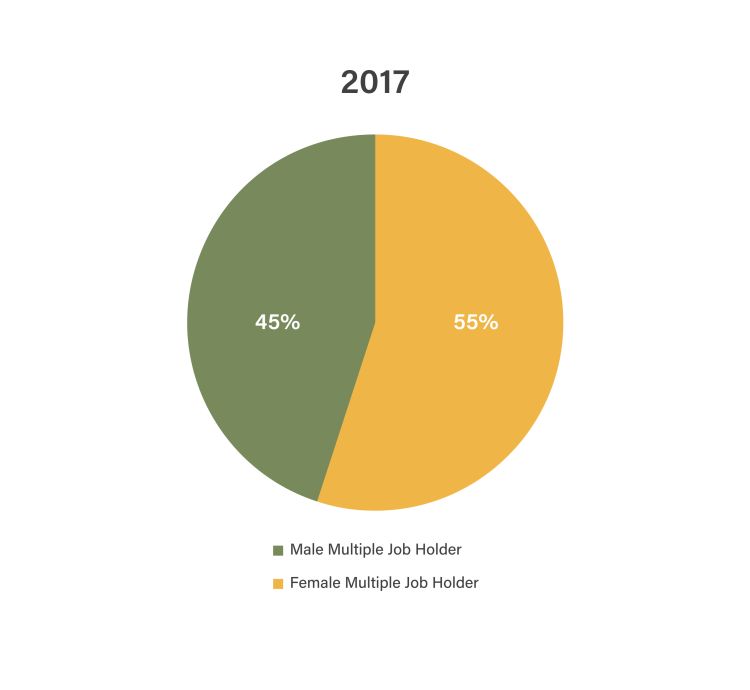

Women also make up a growing proportion of all multiple job holders in this sector, although men have consistently been overrepresented in this category. In 1998, men made up half of multiple job holders in the sector, but only 47% of the sector overall. By 2017, the proportion of men who were multiple job holders (44.6%) was consistent with the proportion of men in the sector (44.7%).

That said, the proportion of multiple job holders across the sector is relatively small: for women it increased from 3.4% to 5.1%, as the proportion of women workers in the sector also increased (see above). Over the same period, the proportion of men in the sector who held multiple jobs increased from 3.4% to 4.1%, though the overall proportion of men in the sector declined. The proportion of temporary female multiple job holders in the sector doubled over this period, from 1.4% to 2.8%.

Academic staff in the university and college sector have also seen some changes as a result of the rise of temporary work. Though the sector has grown, the proportion of academic workers is, on the whole, decreasing: from 35.1% in 1998 to 32.6% in 2017. There is also a shift from permanent to temporary work: the proportion of permanent academic workers decreased over this time period from 76% to 69.3%, and increased for temporary workers from 24% to 30.7%.

Perhaps one of the most interesting trends we noted was in the area of unpaid overtime, which an increasing proportion of academic workers is experiencing. While for the sector as a whole the total amount of unpaid overtime has remained constant, it has increased for academic workers and disproportionately so for temporary academic workers.

In 1998, 23.9% of academic employees worked unpaid overtime, increasing to 27.3% in 2017 (highest in 2010 at 30.9%). While the majority of those academic workers who work unpaid overtime are permanent, fluctuating between 21.9% and 17.9% over the time period, there is a significant jump in temporary workers putting in unpaid overtime, from 5.1% to 9%. Out of all the academic employees working unpaid overtime in 2017, 32.6% were temporary (up from 21.4% in 1998).

This represents a significant amount of time effectively being worked for free. The vast majority of academic workers who work unpaid overtime do so at more than 10 hours a week. This proportion appears to be increasing, though there is some volatility: in 1998 it was 16%, and 16.9% in 2017—though the high point in 2010 was 20.1%.

Of course, there are workers who work fewer than 10 hours a week of unpaid overtime, and this appears to be increasing as well. The proportion of academic workers with between 5 but less than 10 hours a week of unpaid overtime is increasing: from 5.6% in 1998 to 7.3% in 2017. And over the same time period, between 2.2% and 4.4% of academic employees worked less than five hours of unpaid overtime in a week.

This suggests that, based on LFS data, academic workers in Canadian universities and colleges are collectively subsidizing their employers to the tune of 260,000 hours of uncompensated labour each week—and this is very likely an underestimate.

Labour force shifts are not a zero-sum game, and as the post-secondary sector expands as a workforce and through enrolment growth, attention needs to be paid to the broader implications of a move from permanent to temporary employment. Although the shift from permanent to temporary impacts both men and women, a greater proportion of women than men is impacted by the growth in temporary work across the sector. Perhaps most strikingly, while it has remained constant across the sector as a whole, academic workers are working an increasing amount of unpaid overtime – and temporary workers are experiencing a disproportionate increase in unpaid overtime as well. This begs the question: to what extent is the institutional dependence on a more temporary, less permanent workforce—a dependence that will be explored in an upcoming CCPA report—being subsidized by the free labour of the workers themselves?

Erika Shaker is Senior Education Researcher at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Rosa Zetler was the 2018 CCPA summer fellow and is now working as a researcher for United Way Greater Toronto. Special thanks to Robin Shaban for her support in the data analysis for this project.